Housing in the United States: Separate and Unequal

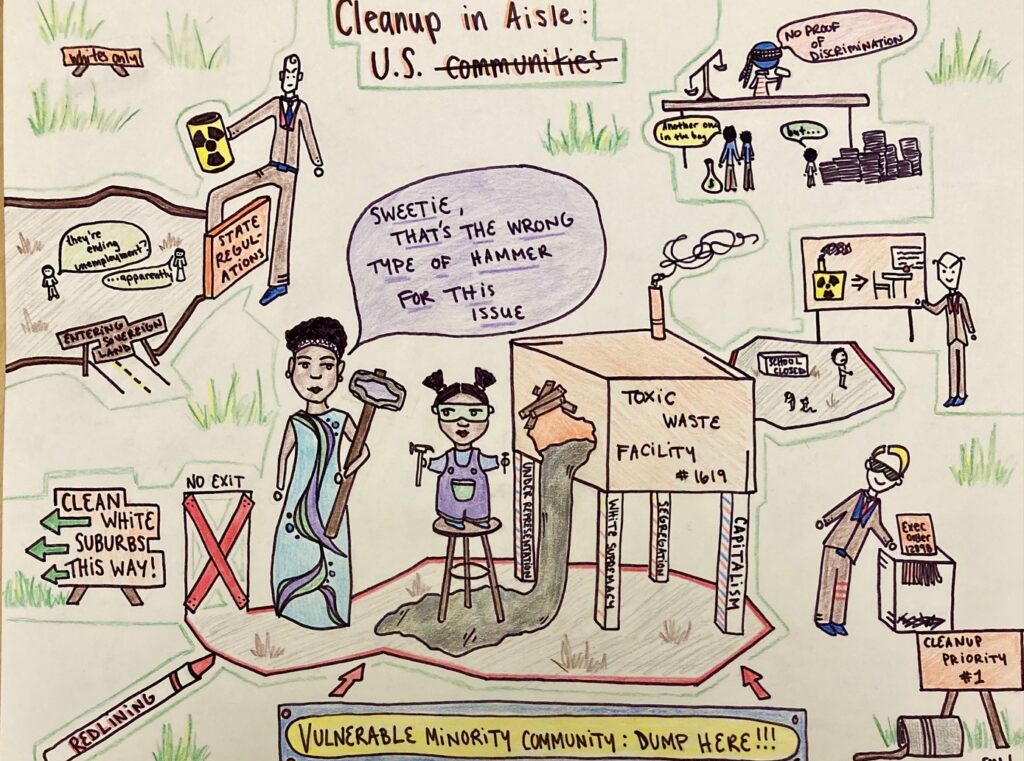

Racist policies and institutions perpetuate inequality. Housing choices for minorities have been historically limited due to racial zoning laws (now illegal but still practiced). These laws allowed banks and companies to deny loans and housing to people of color. Along with the legacies of slavery, exclusion acts, and legal segregation, zoning continues to confine people of color directly and generationally (Whittemore, 2016).

Some White homeowners are hesitant to move into neighborhoods perceived as ‘Black.’ They instead flock to cleaner, Whiter suburbs (known as White flight). Simultaneously, minority homeowners may not be able to move out of or avoid toxic sites (Taylor 2015: 75).

Dumping/Processing Waste in Vulnerable Minority Communities

The most striking effect of this history are communities of color whose vulnerability is exploited by corporations and federal agencies. Toxic and hazardous waste in the US is disproportionately burdened on minority and low-income communities1 .

Waste management companies may offer up jobs and economic incentives to such communities, coercing them to host toxic facilities (Taylor 2015: 142). They are often attracted to minority and low-income areas by low costs/taxes, access to transportation, and decreased likelihood of resistance.

These communities are disadvantaged when negotiating with these powerful companies. They face difficulties caused by underrepresentation in government and lack of information access.

Take for example the Exide battery recycling facility located in Vernon, CA, a low-income community of Latinx immigrants. From the facility, the community has been exposed to over 88 different chemicals. These chemicals seep into the bodies of community members, putting them at elevated risk of cancer.

The company has been noncompliant with state and local regulations for decades. Noncompliance is commonplace; even Federal agencies are inconsistent in following Executive Order 12898, directing them to address environmental racism.

Children are expecially vulnerable to pollutants from plants such as Exide.

Ifran Kahn, Los Angeles Times link

Two lawsuits against the company have been overturned, highlighting the role courts play in environmental racism. Lawsuits are often turned down; discrimination is difficult to prove, and the 14th amendment does not cover private discrimination. Courts may cite the Constitution’s commerce clause. Their decisions often force communities to bear hazardous waste.

In 2020, Exide claimed bankruptcy. Unsurprisingly, courts allowed the company to abandon the site. Companies like this are rarely held accountable, leaving the burden of waste cleanup to local taxpayers. When companies are forced to clean up their waste, Dayley and Layton (2004) found that they clean up cheap and easy sites first instead of the most hazardous.

Exide was aware of the impacts on the community yet continued to prioritize financial benefits to their institution, which mostly go to Whites. Thus, social scientist Laura Pulido understands their actions as a form of White supremacy (2016).

For some, change may be unwanted. “The state is deeply invested in not solving the environmental racism gap because it would be too costly and disruptive to industry, the larger political system, and the state itself” (Pulido 2016). Profits and the ‘good of the nation’ often come before the health of communities, especially devalued communities.

Environmental historian Carl Zimring argues, “waste is a social process” (2015: 1). Thus, challenging environmental racism (also a social process) means fundamentally restructuring systems, altering practices, and challenging the pillars of the country itself.

Note 1: 1987; Ihab Mikati et al. 2018; Pulido, 2016; Pulido, 2015

References: https://soc.hamiltonlits.org/sharingsociology/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Wallis_References.pdf