The Rise of Parramore, Florida:

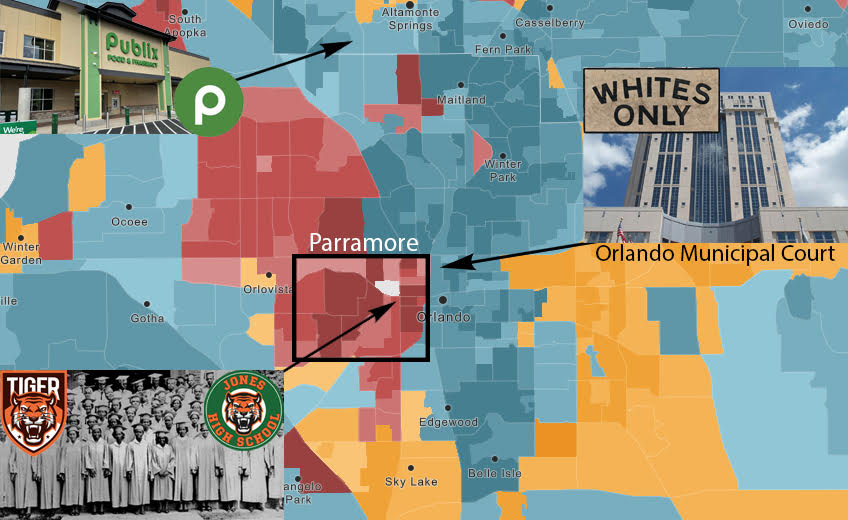

In Florida, during the late 1800s and early 1900s there was much explicit and implicit racism. During this period, Florida had the highest recorded lynchings of Black citzens per 100,000 of any state (Tameka 2005). White people also delimited where Black people could live. Parramore, a segregated Black community right outside of Orlando, resulted from this. Despite its dreadful past, Parramore was able to thrive with: “Black-owned shops lining the streets” (Porter 2004) and a three page directory displaying all the Black-owned businesses which included: hospitals, hotels, theaters, churches and more catered to Black residents.

Desegregation

Desegregation was a crucial part of the civil rights movement and a sensible step in the fight for citizens of color gaining equal rights; Black communities, however, faced many obstacles during integration. As Jim Crow was overturned and desegregation was implemented, racism morphed into many new forms. The people living in these Black communities encountered new and different challenges in education, employment, and interpersonally with whites.

The Impact of Desegregation on Education

Even though schools were integrating and the explicit Jim Crow segregation was taken down, racism morphed into new forms. Dr. Gord Foster, a Florida educator said, “an entire generation of N*gro youth was being sacrificed” (Porter 2004) during this time of transition. When schools were desegregated, problems arose as Black children were bused to predominantly white schools. Black children faced explicit racism in schools through both the negative attitude of the administration and the loss of minority staff. A study by Meyer Weinberg, funded by the National institute of Education, found that “studies of teacher attitudes strongly suggest a generally negative orientation toward minority children” (Sizemore 1978). Additionally, Everett Abney found that from 1965 to 1975 in Florida, 165 new public schools were established but 166 Black public school principals lost their jobs (Sizemore 1978).

In Parramore in 1974, such problems occurred during desegregation. When Black children were forced into white schools, many historically Black schools shut down due to low enrollments. Other predominantly Black schools were converted for other uses. Black children also had to travel far distances to these schools reducing the likelihood of friendships, engaging in school sports and attending community events.

Remaining Black students attended the one local school that survived in Parramore: this school is known today as Jones High School. Jones High School during integration faced many challenges. In 1970, Jones High School was asked to integrate and their staff was given a very short deadline. In response “Officials dropped teachers’ names into a clear pickle jar” and picked at random causing Jones “to lose many of its best staff, including department heads in English, math and science” (Jones High School Historical Society 2018).

Employment Challenges

When the Mayor of Orlando, Carl Langford, called for integration, his call more often than not was ignored. Black people struggled to find employment due to lack of enforcement from the Florida government to integrate. Many stores, such as the highly prevalent supermarket chain known as Publix, refused to hire Black employees. Black people began to boycott stores that refused to hire Black individuals. The 1961 Boycott of Winn-Dixie was a movement by the Black community to boycott the Winn-Dixie stores since they didn’t hire Black people. This boycott opened up some jobs for Black people. However, this development was met with white people boycotting stores that hired Black individuals, harming many stores. (Porter 2004).

Black people faced many challenges when trying to find employment in Parramore, Florida, and the stores that integrated faced challenges, such as boycotts. Since Black people struggled to find employment from white owned businesses in Orlando or other communities outside of Parramore, it affected their ability to leave their segregated communities. Explicit and implicit racism from white communities once again constrained Black communities from integrating.

Interpersonal Racism

Even though Jim Crow segregation officially ended, white people continued various forms of explicit and implicit racism. As the Florida state government called for integration, Black people were allowed to travel to white owned businesses and public spaces in white areas. There, Black people were met with heavy explicit racism. In December 1962 in Parramore for example, “Blacks have been chased out of restrooms at the central Florida fair, the beaches remain closed and signs designating racial space in the municipal court were put up and taken down daily” (Porter 2004).

A Continuing Cycle of Racial Segregation and Inequality:

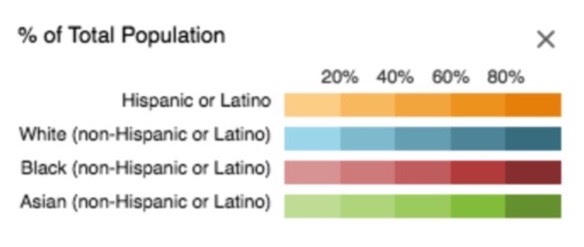

Although Parramore was called to integrate long ago, a census in 2018 found that their population is still 80% Black (US Census 2010), and schools that weren’t shut down during integration in Parramore such as Jones High school are still 99.2% minority and 90% Black (US News 2018). This reveals considerate lingering racial segregation and provokes the question of how much Parramore ever integrated.

References:

Porter, Tana Mosier. 2004. “Segregation and Desegregation in Parramore: Orlando’s African American Community.” The Florida Historical Quarterly, vol. 82, no. 3. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30149526.

Sizemore, Barbara A. 1978. “Educational Research and Desegregation: Significance for the Black Community.” The Journal of Negro Education 47(1):58 https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/educational-research-desegregation-significance/docview/60807197/se-2?accountid=11264

Tameka Bradley Hobbs, “Strange Fruit: An Overview of Lynching in America,” in Go Sound the Trumpet!: Selections in Florida’s African American History, ed. David H. Jackson Jr. and Canter Brown Jr. (Tampa: University of Tampa Press, 2005), 97.

“Race and Ethnicity in Holden-Parramore, Orlando, Florida (Neighborhood)” Cedar Lake Ventures, Inc https://statisticalatlas.com/neighborhood/Florida/Orlando/Holden-Parramore/Race-and-Ethnicity

“Jones High” U.S. News & World Report L.P. https://www.usnews.com/education/best-high-schools/florida/districts/orange-county-public-schools/jones-high-5318

“History of Jones High School 1950-2018” Jones High School Historical Society, Inc https://joneshighschoolhistoricalsociety.org/history1950/