From nacatamal to bulgogi and from my abuela to my halmeoni, my life and identity have been built around the two different cultures I am a part of. Despite loving and cherishing my Korean and Nicaraguan heritage, over my life I have lost components of them.

The time I spent with my halmeoni encompasses most of my childhood memories. Because of her constant presence, I could comprehend and understand Korean to a certain degree. But over the years, as I became engrossed within my extracurriculars and academics, I lost touch with the language, making communication between my halmeoni and I difficult.

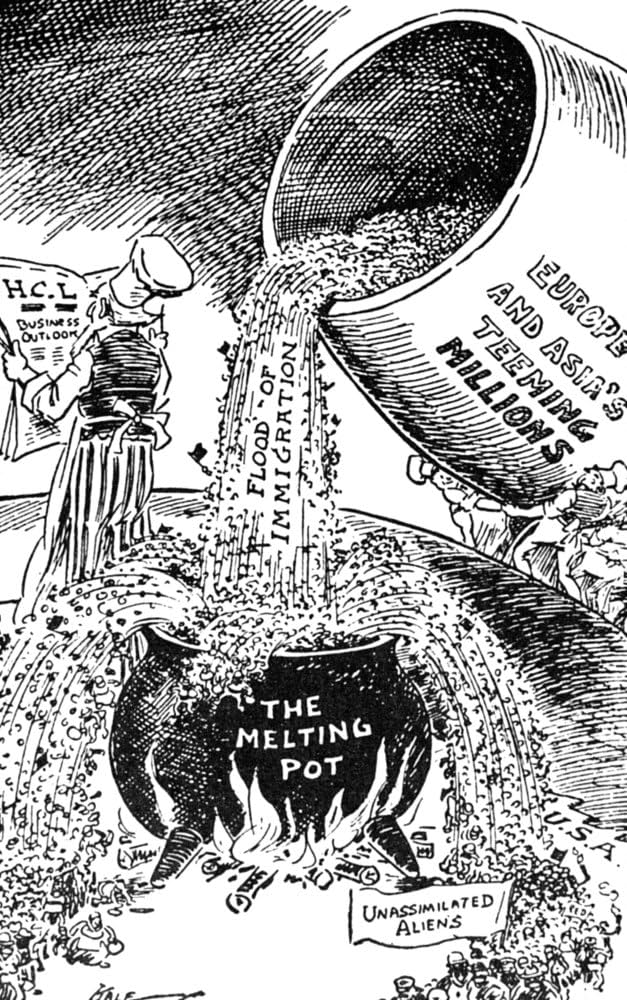

What factors compel second generation Americans to lose connections with their ethnic culture? How does this shed light on American society, a country widely known as a cultural melting pot?

The Intertwining of Culture and Self

Every interaction and event a person experiences shape not only their identity but also their culture (Parisi, Cecconi, and Natale 2003). While both identity and culture can form under similar conditions and intertwine with one another, what happens when two different identities/cultures meet?

Sociologist Domenico Parisi (et al 2003) suggests that given enough time, cultures occupying a similar space will ultimately flow towards cultural homogenization. But this homogenization occurs over many years and over a large population.

In contrast, immigration scholars Portes and Zhou (1993) argue that assimilation does not occur spontaneously, but instead depends on a person’s willingness to be absorbed into mainstream culture.

So what makes someone willing to leave their culture and identity behind in search of something new?

Assimilating towards success

Growing up in second generation families leaves kids and youth conflicted, torn between the demands of their parents and representing the culture they were born into, and the society that they now exist in (Portes et al 1993).

Zhou and Portes (1992) argue that among second generation Americans, socio-economic success and status is a major driving factor for assimilation.

Following WWI European immigrants flooded into the United States. The challenges these immigrants faced in seeking upward mobility were much different than those faced in the 21st century by racially othered minorities such as Asian, Hispanic, and African immigrants. A majority of these European immigrants and their children could keep their culture, according to Portes and Zhou, due to the similarities in social and cultural structures between where they came from and the American norm. By contrast, due to differences in appearances and cultures between Asian, Hispanic, and African immigrants and the white Christian Americans, these racially different groups tended to favor assimilation to achieve social-economic stability and acceptance (Portes et al. 1993).

With the economic gap between the working class and upper class is ever increasing, the need to culturally assimilate in order to achieve economic success only heightens (Glei, Goldman, and Weinstein 2019). Many documented and undocumented immigrants face labor intensive jobs with little to no opportunity for upward mobility. This in turn makes it harder for the children of said immigrants to gain social footing to surpass their parents. By leaving their cultural identity behind, many hope to increase their opportunity for success (Zhou 1997).

By assimilating towards the cultural norm, children of immigrants have better odds of higher economic, educational, and social opportunism despite the background of their parents (Faulkner 2011). If one acts like the successful, should economic success not be more likely?

Professor at ASU Darral Montero, and Professor at UCLA Ronald Tsukashima (1977), suggest this is the case among Japanese-Americans, but it comes at a cost. Measuring the assimilation of Japanese-Americans via their fluency in Japanese and their highest levels of education, Montero and Tsukashima demonstrated a direct correlation between cultural assimilation and success. ⅖ of the people who only spoke English had little to no fluency in Japanese, representing the fully assimilated, reached 4 or more years of collegiate level education. This was in stark contrast to their bilingual counterparts, 20% of whom attained four or more years of collegiate level education (Montero et al. 1977).

Immigrants face further marginalization from speaking other languages in the United States. Because English is the dominant professional and educational language in the US, when immigrants are proficient in another language and not English, adverse psychological effects can propagate (Boureiko 2010). Stigmas surrounding non-English languages in the US can lead to low self-esteem and feelings of inferiority and worthlessness (Boureiko 2010). Children of immigrants may therefore be further tempted to leave their culture and language behind to avoid being marginalized.

Dynamic spatial assimilation

Location plays an important role in determining the rate at which cultural assimilation occurs. Segmented assimilation, defined by Alejandro Portes and Min Zhou (1993), describes how immigrants tend to incorporate themselves into mainstream society, in a manner paced and limited by their social location.

Ethnic enclaves provide a space in which the concept of segmented assimilation is evident. These locations have been established by mass immigration and residential discrimination over many years, especially in large cities like New York City. They provide spaces in which immigrants and their pre-existing culture may flourish. This starkly contrasts from other locations where immigrants find themselves alone in rural or predominantly white areas, lacking the protective barrier that the enclaves provide (Deole and Rieger 2023).

When the concept of segmented assimilation is applied, we can see that within these communities, because they are surrounded by people of the same ethnic and cultural background, assimilation can slow to a near halt. Though first generation immigrants utilize ethnic enclaves as a base of cultural standing within America, their presence only slows the rate at which assimilation will occur in their future generations (Logan, Zhang, and Alba 2002).

Although ethnic enclaves offer a place where pre-existing cultures may be shielded from external judgment and stigma, they may lack access to opportunities economically, socially, and educationally beyond the enclave (Logan et al. 2002). Second generation Americans may seek to leave enclaves to access other educational and economic opportunities (Logan et al. 2002).

Navigating the Truth

I find myself constantly wondering if my own ethnic identities are a result of personal choice. Did refusing to bring ethnic food to grade school stem from a need to fit in? Though personal pressure and thoughts may have played a role, the overarching systemic pressure to culturally assimilate seems to aid success, especially in the United States as second generation Americans.

References

Boureiko, Natalya V. 2010. “Factors Influencing the Academic Success of Second Generation Immigrant College Students.” Order No. 3413922 dissertation, University of Arkansas at Little Rock, United States — Arkansas (https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/factors-influencing-academic-success-second/docview/750175266/se-2).

Deole, Sumit S., and Marc O. Rieger. 2023. “The Immigrant-Native Gap in Risk and Time Preferences in Germany: Levels, Socio-Economic Determinants, and Recent Changes.” Journal of Population Economics 36(2):743-778 (https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/immigrant-native-gap-risk-time-preferences/docview/2777521577/se-2). doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-022-00925-x.

Glei, Dana A., Noreen Goldman, and Maxine Weinstein. 2019. “A Growing Socioeconomic Divide: Effects of the Great Recession on Perceived Economic Distress in the United States.” PLOS ONE 14(4)(https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0214947#ack)

Logan, John R., Wenquan Zhang and Richard D. Alba. 2002. “Immigrant Enclaves and Ethnic Communities in New York and Los Angeles.” American Sociological Review 67(2):299-322 (https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/immigrant-enclaves-ethnic-communities-new-york/docview/218769406/se-2). doi: https://doi.org/10.2307/3088897.

Montero, Darrel and Ronald Tsukashima. 1977. “Assimilation and Educational Achievement: The Case of the Second Generation Japanese-American.” The Sociological Quarterly 18(4):490–503. (https://www.jstor.org/stable/4105697?seq=7).

Faulkner, Caroline L. 2011″Economic Mobility and Cultural Assimilation among Children of Immigrants.” Contemporary Sociology 41(5):688 (https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/economic-mobility-cultural-assimilation-among/docview/1041084919/se-2). doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0094306112457771e.

Parisi, Domenico, Federico Cecconi, and Francesco Natale. 2003. “Cultural Change in Spatial Environments.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 47(2):163–79 (https://www.jstor.org/stable/3176165?seq=1).

Portes, Alejandro, and Min Zhou. 1993. “The New Second Generation: Segmented Assimilation and its Variants.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 530:74-96 (https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/new-second-generation-segmented-assimilation/docview/61767103/se-2).

Zhou, Min. 1997. “GROWING UP AMERICAN: The Challenge Confronting Immigrant Children and Children of Immigrants.” Annual Review of Sociology 23:63-95 (https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/growing-up-american-challenge-confronting/docview/199591904/se-2).