Picture this. You are walking down 135th street in Harlem. On your right, you spot a park in the distance. As you walk closer, you can hear a basketball bouncing and kids yelling. It’s a small, outdoor court, well-maintained with fresh paint and a sturdy chain-link fence surrounding it. The game is intense, with everyone giving their all. The ball is constantly in motion, being passed, dribbled, and shot from all angles. As the game progresses, the excitement draws in more kids around the court.

New York City is a city that is synonymous with basketball. From the playgrounds of Harlem, to the courts of Brooklyn, basketball has been a part of the city’s culture for decades. But why has basketball become such a staple of African American culture in cities? The answer is complex, but the roots of popularity among minority groups in the city stem from discriminatory practices like redlining and segregation.

A White Man’s Sport

“Basketball was originally invented as a white man’s game” – Micheal Novack, The Joy of Sports (1946)

In order to understand the history of basketball in NYC, we must start at its founding. Basketball was founded in 1891 by Dr. James Naismith, a Canadian physical education instructor who was seeking a way to keep his students active. Basketball quickly gained popularity, and by the early 1900s, it was being played in colleges and high schools across the United States. For example, colleges like Harvard, Yale, Cornell and Princeton began to play games against each other as early as 1901. The first professional basketball league, the National Basketball League (NBL), was founded in 1937. It was later merged with the Basketball Association of America (BAA) to form the National Basketball Association (NBA) in 1949 (Pearson 2022).

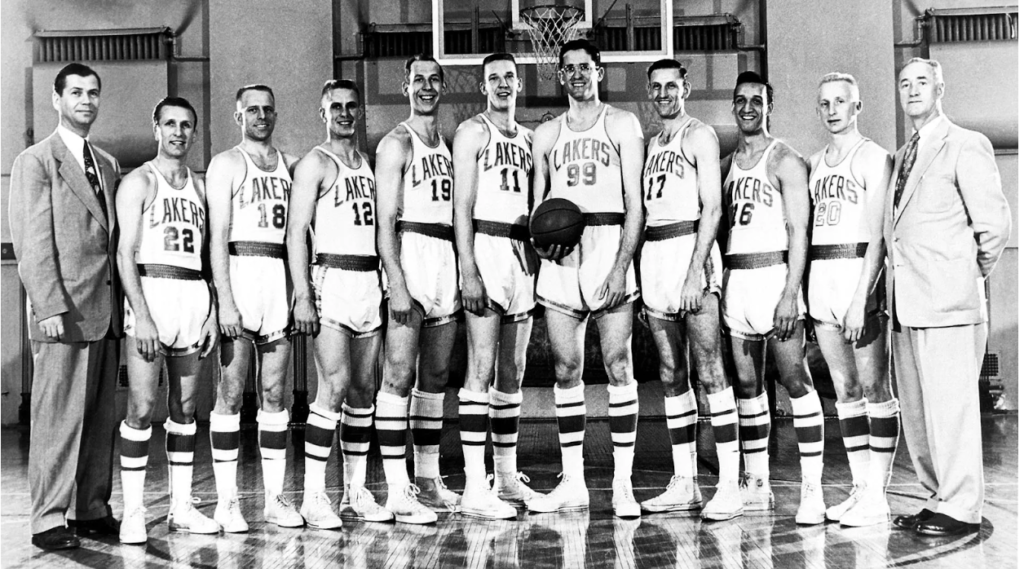

Minneapolis Lakers 1949-1950 season (NBA 2023)

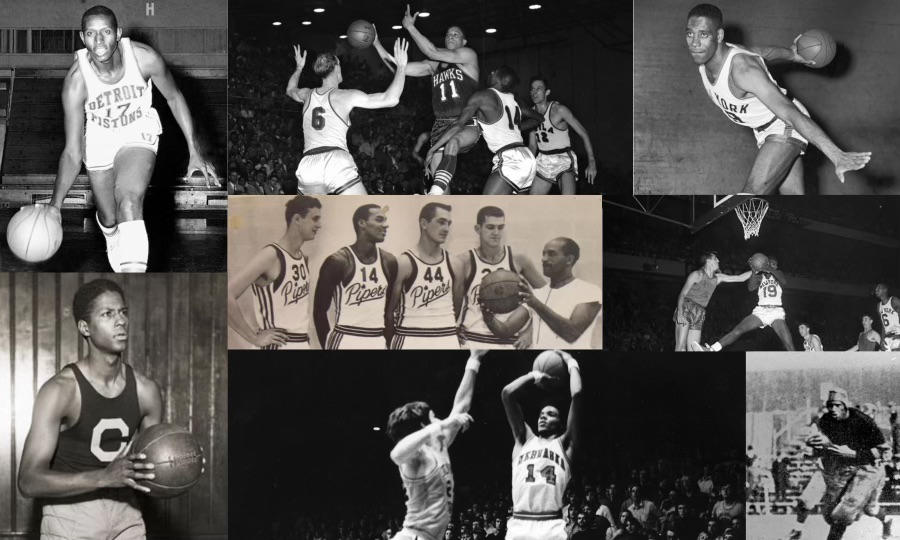

For the first 30 years of basketball’s early history, the majority of participants at the collegiate and professional level were white, as black participants were barred from playing. The first black collegiate player, George Gregory Jr, did not appear until 1928. In the 1949-1950 season Chuck Cooper, Nathaniel Clifton, and Earl Lloyd became the first black players to play professional basketball, finally breaking the existing color barrier (Pearson 2022).

Social pressure stemming from segregation in the early 1900s as well as economic discrimination toward minorities stifled black participation in basketball’s early history. Basketball at this time was played mostly at community centers like YMCAs, wherewhite owners refused membership to black people. There were no outside courts at this time. If black people wanted to play basketball, they would need to build their own.

NYC’s History Of Racial, Economic, and Athletic Segregation

Redlining and other forms of economic discrimination depressed resources in minority neighborhoods. Redlining is an exclusionary practice that began in 1934 with the implementation of the National Housing Act (NHA). The NHA created a bunch of government programs such as the Federal Housing Association (FHA) and the HomeOwner Loan Corporation (HOLC) with the intent to improve the housing market. Its mission was to promote homeownership by providing mortgage insurance to lenders, which would make it easier for people to obtain loans to buy homes. While the FHA improved housing conditions for White people at the time, this support largely excluded black people.

The HOLC wrote dozens of reports to banks which categorized areas with large populations of black residents as “risky” for investors, driving down their property values and scaring off many potential investors. The FHA then used these maps to guide its lending policies, which meant refusing to give minorities federally insured housing loans for houses in certain areas (Hunt 2022). In addition to this, as more black people began moving to white neighborhoods in northern cities in efforts to escape Jim Crow segregation, white people began to create suburbs outside the city to escape the influx of black people. As more white homeowners fled to the suburbs, the remaining ones agreed to sell their homes at deeper discounts, fearful of falling prices.

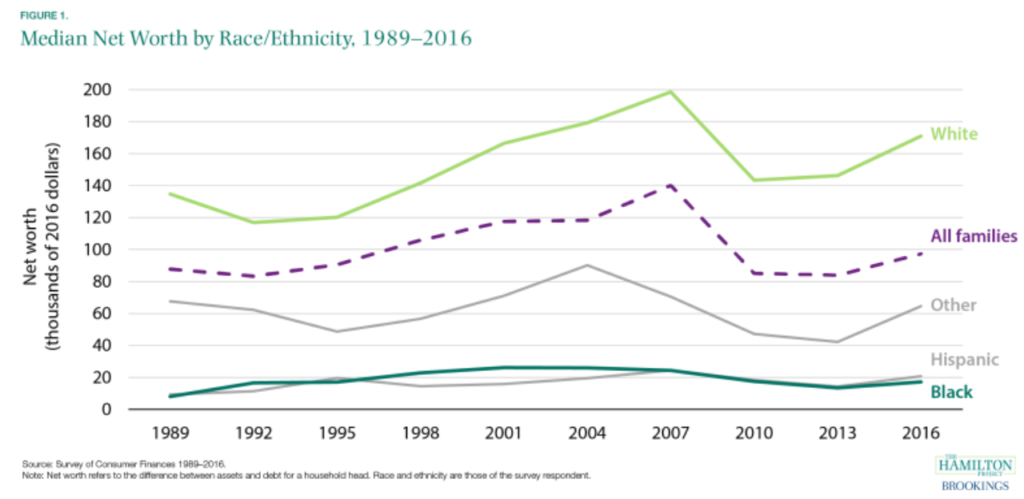

Princeton economics professor Leah Bouston found that, for every Black resident who moved into a northern or western city from 1940-1970, two white residents left for the suburbs. White flight and disinvestment caused by redlining made already poor neighborhoods poorer, and widened the wealth gap between white and black households (McIntosh 2022).

(Brookings Project 2022)

Economic inequality caused by redlining practices also created disparities in the types of sports played by the kids in poorer neighborhoods. Redlined neighborhoods have less green space, subpar schooling and have smaller parks on average (Schweber 2020). In contrast to minority neighborhoods, affluent white neighborhoods on the upper west side of Manhattan had big townhouses, clean sidewalks, lawns, ball parks, and waterfront views. According to an analysis by the Trust for Public Land, the average park size is 6.4 acres in poor neighborhoods, compared with 14 acres in wealthy neighborhoods in New York City (Schweber 2020). Sports such as baseball and football, which require space and money to participate in, were less likely to be played in poorer neighborhoods because they didn’t have the space or public funding to build them (Ogden 2003).

In addition to less space and available parks, another reason minority children gravitated toward basketball is because of the cost of entry barriers that other sports carried. For example, in order to play baseball at a high level, you need money to pay for equipment and travel teams. Basketball did not carry this prerequisite. David C Ogden, a professor at the University of Nebraska who studied race and sport dynamics, wrote that the most common reasons for the lack of racial diversity were the paucity of baseball facilities in Black neighborhoods, and the cost of playing select baseball (Ogden 2003). As a result:

“More than two-thirds of the 27 coaches said that African-American youth prefer to spend their time on the basketball court rather than on the diamond” (Ogden 2003)

Rise of Black YMCAs

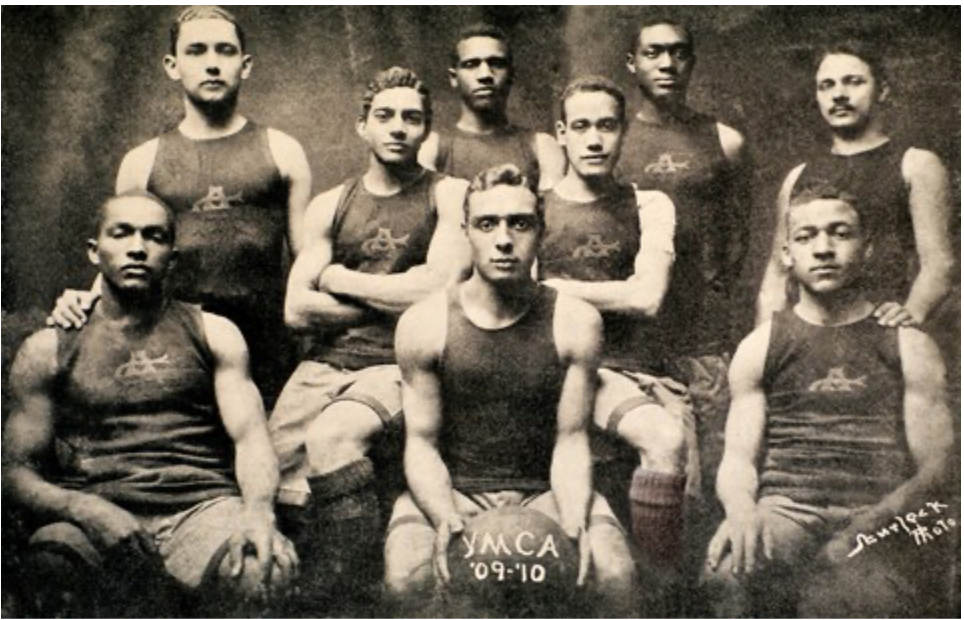

Basketball’s popularity among minority communities flourished because of the development of black YMCA’s. African Americans, Irish or Jewish people used these centers as a way to build community, and develop a common identity through sports. The Smart Set Athletic Club of Brooklyn would be the first fully independent Black basketball team in America in 1907 (Gay 2021). As more and more YMCA’s appeared in major cities, basketball spread in similar fashion.

Edwin Bancroft Henderson, an educator working in Washington D.C., introduced the game of basketball to the Black community. Henderson learned the game during summer sessions at Harvard University, and then introduced the game to young Black men upon returning to the Washington D.C. area in his Phys Ed. class. Soon the game would be played across the east coast of the United States, mainly in New York, Philadelphia and Baltimore.

“In the last game of the season, the 12th Streeters beat the Smart Set in Brooklyn 20:17 in front of more than 2,000 spectators and in this way directly dethroned the reigning champion.” (Domke 2011)

In addition to community building, basketball started to become a means for economic upward mobility. The Harlem Globetrotters formed in 1926 and became the most renowned basketball team for black basketball players. For black basketball players, the globetrotters provided the best and only way to make a living while playing basketball (Ezekiel 2021). After minority children saw people like them achieve their dreams, they started to believe it was attainable.

Basketball Today

Now, basketball is an important part of NYC culture, regardless of race. Black participation in basketball has soared in the decades after segregation, and has especially soared in NYC (Centopani 2020). Every summer, minority communities gather for basketball tournaments held in NYC parks, some that even draw national attention. Nike sponsored “NY vs NY” and Slam magazine’s Summer Classic feature the top ranked high school players and have thousands of fans watching every summer. They both have been held in Dyckman park in Manhattan for the past 5 years.

Significant changes have occurred in professional demographics as well. In contrast to 1950, 75 % of the NBA is black, with a bunch of black athletes playing abroad in leagues all over the world (Bowen 2017). Segregation and redlining stifled black participation in basketball in its early history, but the economic conditions it fostered helped basketball become such an enduring staple of the community for future generations.

References:

Aaronson, D., Faber, J., Hartley, D., Mazumder, B., & Sharkey, P. (2020). The Long-Run Effects of the 1930s HOLC “Redlining” Maps on Place-Based Measures of Economic Opportunity and Socioeconomic Success. The Effects of the 1930s HOLC “Redlining” Maps. https://doi.org/10.21033/wp-2020-33

Bowen, F. (2023, April 7). In its early years, NBA blocked black players. The Washington Post. Retrieved April 24, 2023, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/kidspost/in-nbas-early-years-black-players-werent-welcome/2017/02/15/664aa92e-f1fc-11e6-b9c9-e83fce42fb61_story.html

Centopani, P. (2020, February 24). The makings of basketball mecca: Why it will always be New York. FanSided. Retrieved May 1, 2023, from https://fansided.com/2020/02/24/makings-basketball-mecca-will-always-new-york/

Domke, M. (2011). Into the vertical: Basketball, urbanization, and African American … Into the Vertical: Basketball, Urbanization, and African American Culture in Early- Twentieth-Century America. Retrieved March 31, 2023, from http://www.aspeers.com/sites/default/files/pdf/domke.pdf

Gay, C. (2022, January 13). The black fives: A history of the era that led to the NBA’s racial integration. Sporting News Canada. Retrieved April 24, 2023, from https://www.sportingnews.com/ca/nba/news/the-black-fives-a-history-of-the-era-that-led-to-the-nbas-racial-integration/8fennuvt00hl1odmregcrbbtj

Gorey, J. (2022, July 25). How “White flight” segregated American cities and Suburbs. Apartment Therapy. Retrieved April 30, 2023, from https://www.apartmenttherapy.com/white-flight-2-36805862

Hunt, M. (2022, October 11). What is the National Housing Act? Bankrate. Retrieved April 25, 2023, from https://www.bankrate.com/real-estate/the-national-housing-act/#:~:text=What%20is%20the%20National%20Housing%20Act%20(NHA)%3F,Loan%20Insurance%20Corporation%20(FSLIC).

Hu, W., & Schweber, N. (2020, July 15). New York City has 2,300 parks. but poor neighborhoods lose out. The New York Times. Retrieved April 21, 2023, from https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/15/nyregion/nyc-parks-access-governors-island.html

Ivy league regular season champions, by Year. Coaches Database. (2023, March 5). Retrieved April 24, 2023, from https://www.coachesdatabase.com/ivy-league-regular-season-champions/

McIntosh, K., Moss, E., Nunn, R., & Shambaugh, J. (2022, March 9). Examining the black-white wealth gap. Brookings. Retrieved April 25, 2023, from https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2020/02/27/examining-the-black-white-wealth-gap/

Ogden, D. C. ., & Hilt, M. L. . (2003). Collective Identity and Basketball: An Explanation for the Decreasing Number of African Americans on America’s Baseball Diamond. Retrieved March 31, 2023, from https://www.nrpa.org/globalassets/journals/jlr/2003/volume-35/jlr-volume-35-number-2-pp-213-227.pdf

Ortigas, R., Okorom-Achuonyne, B., & Jackson, S. (n.d.). What exactly is redlining? Inequality in NYC. Retrieved March 30, 2023, from https://rayortigas.github.io/cs171-inequality-in-nyc/

Pearson, S. (2022). Basketball origins, growth and history of the game. History of The Game Of Basketball Including The NBA and the NCAA. Retrieved April 24, 2023, from https://www.thepeoplehistory.com/basketballhistory.html

Robertson, N. M. (1995). [Review of Light in the Darkness: African Americans and the YMCA, 1852-1946., by N. Mjagkij]. Contemporary Sociology, 24(2), 192–193. https://doi.org/10.2307/2076853

Townsley, J., Nowlin, M., & Andres, U. M. (2022, August 18). The lasting impacts of segregation and redlining. SAVI. Retrieved March 30, 2023, from https://www.savi.org/2021/06/24/lasting-impacts-of-segregation/