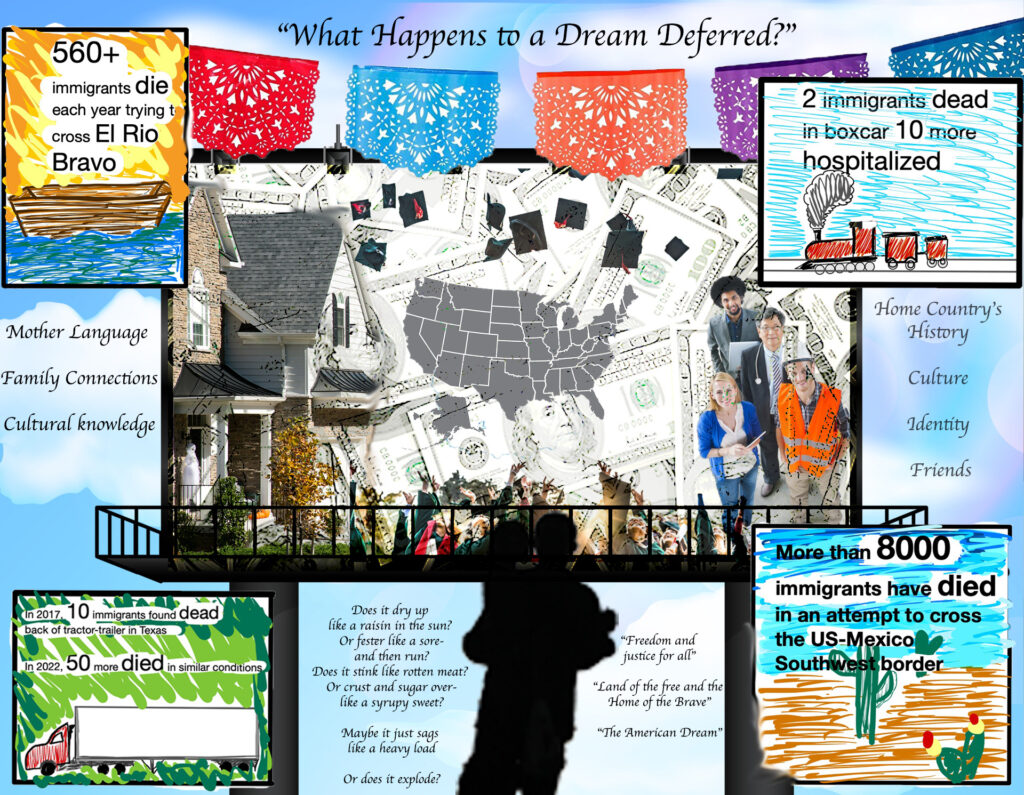

The opening line of Langston Hughes’ poem Harlem asks, “What happens to a Dream Deferred?” The poem speaks about the pain of not realizing one’s dreams amid the racial inequalities Black Americans faced in the 1960s. Likewise, people impacted by the Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors Act (DREAMers) currently face the pain of deferred dreams. The dreams of being treated with equality, not having their identity questioned, and obtaining the citizenship of the country that watched them grow up are deferred.

Harlem

“What happens to a dream deferred?

Does it dry up

like a raisin in the sun?

Or fester like a sore—

And then run?

Does it stink like rotten meat?

Or crust and sugar over—

like a syrupy sweet?Maybe it just sags

like a heavy load.Or does it explode?“

Langston Hughes

Citizenship Limbo

The federal government’s policy for Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) was passed on June 15th, 2012. The policy allows DREAMers to obtain a driver’s license, in-state college tuition, federal aid, and professional licensing credentials. However, it does not provide a path to citizenship (Rosenberg et al., 2020).

DACA recipients have been allowed to grow up in this country , but the losses they face in pursuing the American dream, such as connections to family in their countries of origin, are overlooked. DACA recipients cannot visit their home countries. Some have not returned to their home countries or seen relatives in decades (Ruth et al. 2019).

DREAMers learn the culture and the history of the United States. Yet, they do not obtain any of the benefits that come with becoming a citizen. DREAMers are not allowed to vote or allowed access to affordable healthcare, or social security numbers (Ruth et al. 2019). The drivers license clause, should be noted, only applies to some states which allow DREAMers to obtain a drivers license (ncsl.org). The only financial assistance DREAMers are given toward healthcare is for emergency care. Otherwise, if they go see a doctor they have to pay out of pocket.

Adopting Culture

DREAMers have guaranteed access to public education, but not access to college. In 1982, the U.S Supreme Court in Plyler v. Doe ruled in favor of allowing undocumented children access to public education for K-12 schooling. The schools in which children are enrolled are not allowed to release any immigration information to immigration authorities (National Immigration Forum, 2023). For at least 12 years of their lives, DREAMers learn about the history, customs, and pledge allegiance to a country not in allegiance with them.

Nevertheless, if DREAMers apply to college, they face the challenge of paying for it. College as financial aid for DREAmers is not guaranteed (Rosenberg et al., 2020). Financial assistance, such as FAFSA, is not available for people without a valid social security number. If DREAMers manage to attend college, their likelihood of graduating is low ( 4%), compared to their citizen counterparts (18%) (migrationpolicy.org)

“I remember the moment I realized how much my immigration status impacted me. There was a big push in high school for everyone to apply for financial aid, and I told my teacher I didn’t have a social security number. My teacher looked upset, and it made me feel hopeless and embarrassed. She couldn’t do anything to help me. It made me feel dumb.”

– Anonymous

(Rosenberg et al., 2020)

Identity Discord

Arguably one of the biggest losses of DACAmented people is cultural identity. Children adopt ideas, language, and culture from their environment (Raburu, 2015). That means undocumented children are adopting American culture arguably even more than their home countries.

However, even with all the American markers of identity such as their mannerisms, fashion, and diction (Ruth et al. 2019), their American identity is questioned or invisible in the US. For example, some DREAMers recall people telling them they are not American as they do not have “papers” even though they grew up in the US (Ruth et al. 2019).

“You adopt American culture, principles, ideas, mannerisms, but there’s somebody out there, because of your lack of documentation, that’s going to tell you, ‘You’re not American.’”

– Eduardo

(Ruth et al. 2019)

Their American markers of identity are visible enough for Mexican DACA recipients to be considered American tourists in Mexico (Ruth et al. 2019). People in Mexico pick up on their mannerisms and assume they are “del norte”- from the north- meaning they had money and privilege (Ruth et al. 2019). However, with 14% of immigrants living below the poverty line of $27,500, privilege is hardly reflected (migrationpolicy.org)

Emerging Fear

The feelings of fear and anxiety created by DREAMers’ deferred dreams are real and have real consequences. Upon first learning of their undocumented status in the US, the youth feel helpless, anxious, and alienated (Rosenberg et al., 2020). As children, many are taught to keep their story secret. It can be dangerous if the wrong people find out. That leads to the feeling of alienation. Whom can they trust? Who would understand their feelings if no one knows what they are going through? Moreover, some DREAMers were bullied for their heritage.

“I hated walking down the hallway during high school because the girls made fun of my long black hair. I hated myself for not looking like them. I had low self-esteem.”

– Anonymous

(Rosenberg et al., 2020)

Helplessness arises when they realize they do not have the power to change anything. Finally, anxiousness settles in as the secret they carry consumes their insides and restricts their future possibilities (Rosenberg et al. 2020).

“I never shared my status. I did not want my friends to look at me differently. I had a secret. I wasn’t popular and I didn’t want anyone to know about me.”

– Anonymous

(Rosenberg et al., 2020)

The Negative Feelings Resurface

On September 5, 2017, the Trump administration revoked the DACA program through executive order (Aranda et al., 2023). Due to legal challenges, the order was overruled by the Supreme Court in 2020. DACA is still protecting peoples’ legal status but not taking any new applications (Aranda et al., 2023). The action taken made DREAMers feel hopelessness and anger regarding the uncertainty of DACA.

“Like honestly when you have a president, when you have someone that literally says that you’re evil. It’s like, I don’t know, it’s not the same anymore. You feel like you’re not welcomed. You feel like you’re unwanted.”

– Claudio

(Aranda et al., 2023)

The safety net that had been given to them by the Obama administration was ripped away by the Trump administration. As a result, some DREAMers began accelerating their course of study, some took up more time to work, some switched careers, and others abandoned their dreams altogether (Aranda et al., 2023). In extreme cases, people attempted suicide (Aranda et al., 2023). Although the actions of the Supreme Court protect DREAMers from deportation today, their future is still uncertain.

“I got really scared, like, I got sad, and I started thinking—I started feeling hopeless, you know, like, just more of, like, “Oh, like, now, I have to really think, like—” I was also pressured, like, I felt like there was, like, a time clock thing, because my DACA will expire”

– Alicia

(Aranda et al., 2023)

Help From Outsiders Within

DREAMers help the American economy grow and society function. In 2021, more than 1/3 of DACA recipients held jobs deemed essential by the Department of Homeland Security’s Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency. They work as healthcare workers, educators, and food supply chain workers. Together 343,000 DREAMers are actively working and paying taxes. In fact, DACA-recipient households make up $6.2 billion in federal taxes and $3.3 billion in state and local taxes paid each year.

Additionally, in local economies, DACA-recipient households hold $25.3 billion in spending power (Livingcost.org). However, the aid provided by DREAMers is not just recent. They have provided US aid in financial stability throughput time.

National American Economy (2019)

DACA recipients have proven they can aid the US, yet the US refuses to recognize them as their own. DREAMers deserve better than an uncertain future as they grew up in the US and currently help the US grow. They adopt the culture of Americans but are not considered Americans. If this country watched them grow- built them- why not continue empowering them to be full members of American society? Why put them in a box with restricted possibilities? They have proven they want to work, study, and help. So, why defer their dreams?

References

Anon. 2019. “Overcoming the Odds: The Contributions of DACA-Eligible Immigrants and TPS Holders to the U.S. Economy.” New American Economy Research Fund. Retrieved April 19, 2023

(https://research.newamericaneconomy.org/report/overcoming-the-odds-the-contribution s-of-daca-eligible-immigrants-and-tps-holders-to-the-u-s-economy/).

Anon. 2022. “Fact Sheet: Undocumented Immigrants and Federal Health Care Benefits.” National Immigration Forum. Retrieved April 8, 2023

(https://immigrationforum.org/article/fact-sheet-undocumented-immigrants-and-federal-h ealth-care-benefits/).

Anon. 2023. “Brief States Offering Driver’s Licenses to Immigrants.” National Conference of State Legislatures. Retrieved April 17, 2023

(https://www.ncsl.org/immigration/states-offering-drivers-licenses-to-immigrants).

Aranda, Elizabeth, Elizabeth Vaquera, Heide Castañeda, and Girsea Martinez Rosas. 2023. “Undocumented Again? DACA Rescission, Emotions, and Incorporation Outcomes among Young Adults.” Social Forces. Retrieved March 18, 2023

(https://muse.jhu.edu/article/881218).

Jie Zong, Ariel G. Ruiz Soto. 2018. “A Profile of Current DACA Recipients by Education, Industry, and Occupation.” Migrationpolicy.org. Retrieved April 19, 2023

(https://www.migrationpolicy.org/research/profile-current-daca-recipients-education-indus try-and-occupation).

McArdle, Elaine. 2015. “What about the Dreamers?” Harvard Graduate School of Education. Retrieved April 8, 2023

(https://www.gse.harvard.edu/news/ed/15/08/what-about-dreamers).

Raburu, Pamela A. 2015. “The Self- Who Am I?: Children’s Identity and Development. Richtmann.” Journal of Educational and Social Research . Retrieved March 4, 2023 (https://www.richtmann.org/journal/index.php/jesr/article/view/5600).

Rosenberg, Jessica, Sally Robles, and Astrid Casasola. 2020.

“What Happens to a Dream Deferred? Identity Formation and DACA.” Sage Journals . Retrieved March 3, 2023

(https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0739986320936370).

Ruth, A., Emir Estrada, Stephanie Martinez-Fuentes, and Armando Vazquez-Ramos. 1970.

“Soy the Aqui, Soy De Alla: Dacamented Homecomings and Implications for Identity and Belonging: Semantic Scholar.: Latino Studies. Retrieved March 3, 2023

(https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Soy-de-aqu%C3&AD%2C-soy-de-all%C3%A1% 3A-DACAmented-homecomings-Ruth-Estrada/1b2318b2dba9d6dd35df1e72b59b48fa28 ).

Svajlenka, Nicole Prchal and Trinh Q. Truong. 2021. “The Demographic and Economic Impacts of DACA Recipients: Fall 2021 Edition.” Center for American Progress. Retrieved March 22, 2023

(https://www.americanprogress.org/article/the-demographic-and-economic-impacts-of-da ca-recipients-fall-2021-edition/).

Art Piece References

Black, Julia. 2018. “Migrant Deaths Remain High despite Sharp Fall in US-Mexico Border Crossings in 2017.” International Organization for Migration. Retrieved March 28, 2023 (https://www.iom.int/news/migrant-deaths-remain-high-despite-sharp-fall-us-mexico-bord er-crossings-2017).

Calderin, Gilberto. 2022. “Explainer: Migrant Deaths at the Border.” National Immigration Forum. Retrieved March 28, 2023

(https://immigrationforum.org/article/explainer-migrant-deaths-at-the-border/).

Gans, Jared. 2023. “Two Migrants Found Dead in Texas Train Car, at Least 10 Hospitalized.” The Hill. Retrieved March 28, 2023

(https://thehill.com/latino/3917742-two-migrants-found-dead-in-texas-train-car-at-least-10 -hospitalized/). Rose, Joel and Marisa Peñaloza. 2022. “Migrant Deaths at the U.S.-Mexico Border Hit a Record High, in Part Due to Drownings.” NPR. Retrieved March 28, 2023 (https://www.npr.org/2022/09/29/1125638107/migrant-deaths-us-mexico-border-record-d rownings).