As hospitals have become busier in recent years, physician-led labor has replaced midwife-led labor. Today, midwives are only present at 12% of US births (OSHU 2020). With the prioritization of safe medical practices, present-day society has traded woman-centered approaches to childbirth, like midwifery, for more sterile medical approaches (Sandall et al. 2010).

The busy hospital setting in the US allows little time for midwives to fulfill the duties of their jobs, leaving patients without the emotional and physical assistance of a trusted medical professional. How can we simultaneously hold space for medically safe practices while also keeping the mother’s emotional experience of labor in mind?

Labor in Hospitals Today

Birth can be traumatizing. It is extremely physically demanding and mentally strenuous. Today, hospitals are overwhelmed and have little time to address the mental challenges labor can elicit. In most hospitals today, around 46% of women are left alone during labor (Sehhatie et. al 2014). Many women report feeling scared and abandoned during their labor experiences. This is often because of a lack of patient-physician communication, causing worries about their health and their child’s health (Sehhatie et. al 2014).

Stress during labor can cause muscle contractions, which can increase labor pain. This can, in turn, slow the fetal heart rate and complicate the delivery (Goldenberg and McClure 2011). So, if we prioritize woman-centered care in hospitals and utilize midwifery as a method of providing emotional care to mothers, both the baby and mother will benefit physically and mentally.

Midwives’ Emotional and Physical Care

Midwives are certified medical professionals who assist with uncomplicated births. They perform tasks such as monitoring fetal heart rate, assisting with the delivery, and administering drugs (Sehhati et al 2014). However, the most important part of a midwife’s job has traditionally been to provide continuity of care to the patient. This means that while doctors may come in and out of the delivery room, the midwife stays beside the mother. The midwife builds rapport with the patient and keeps her updated about her delivery (Sandall, et al 2010).

Woman-centered care is a form of care that combines both clinical skills and emotional intelligence on the part of the provider (Towler and Bramall 1986). It emphasizes the physical and emotional presence of the mother as an active and important player in the labor process, rather than passively watching decisions being made about their health around them (Sandall et.al 2010). Although women report midwifery positively impacts their labor experiences, many hospitals today do not implement continuity of care due to the overtaxed hospital setting (Sandall, et al. 2010).

Medicalizing Midwives

Hospitals have become overburdened as healthcare has become more privatized (Chang et al 2019). With patients overflowing into the hallways of some US hospitals, there is little time for midwives to implement continuity of care (Chang et al. 2019). On average, midwives only spend about one-fourth of their time assisting women in the delivery room. They are often assigned to multiple patients at a time, making it necessary for them to split their time between rooms (Sehhatie et. al 2014). When midwives aren’t directly interacting with patients, they are often preoccupied with their clinical duties, such as fetal monitoring and paperwork. These duties leave little time for patient-midwife bonding and render continuity of care near impossible.

Source: Community Medical Centers, 2019

The Future of Midwifery

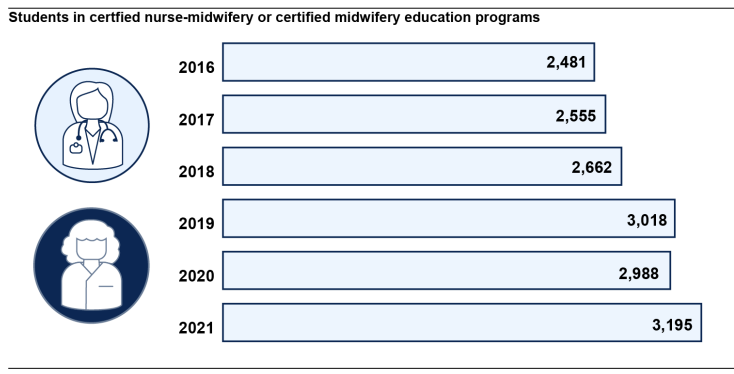

With an increasing emphasis on physical care rather than mental care and increasingly strained hospitals in the US, it is difficult to imagine an optimistic future for midwifery. However, while the percentage of midwife-attended births in the US is still small, it has increased since 2016 (GAO 2023). Additionally, over the past 8 years, the number of official certifications given out for midwifery has increased (GAO 2023). While midwifery may not yet be a widespread practice, there is hope for a future in which midwives have more space in the medical world.

Source: United States Government Accountability Office, 2023

References

Chang, Bernard P., and George Gallos, and Lauren Wasson, and Donald Edmondson. 2019. “The Unique Environmental Influences of Acute Care Settings on Patient and Physician Well-being: A Call to Action.” The Journal of Emergency Medicine 54(1):19-21.

Community Medical Centers 2019. “Should I Go To the Emergency Room, an Urgent Care or My Primary Care Physician?”. Retrieved April 24, 2024 (https://www.communitymedical.org/about-us/newsroom/should-i-go-to-the-emergency-room)

Goldenberg, Robert L. and Elizabeth M. McClure. 2011. “Maternal Mortality”. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 205(4):293-295.

OHSU Center for Women’s Health. “A Brief History of Midwifery in America.” Oregon: Oregon Health and Science University. Retrieved March 4, 2024. (https://www.ohsu.edu/womens-health/brief-history-midwifery-america#:~:text=In%20th e%20early%20parts%20of,United%20States%20births%20in%202020)

Sandall, Jane, Declan Devane, Hora Soltani, Marie Hatem, and Simon Gates. 2010. “Improving Quality and Safety in Maternity Care: The Contribution of Midwife-Led Care”. Journal of Midwifery and Women’s Health: 55(3):255-261

Sehhatie, Fahimeh, Maryam Najjarzadeh, Vahid Zamanzadeh, and Alehe Seyyedrasooli. 2014. “The Effect of Midwifery Continuing Care on Childbirth Outcomes”. Iranian Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Research. 19(3): 233–237.

Towler, Jean and Joan Bramall. 1986. Midwives in History and Society. Oxfordshire: Taylor and Franscis

United States Government Accountability Office 2023. “Information on Births, Workforce, and Midwifery Education”. Washington, DC: United States Government Accountability Office. Retrieved April 24, 2024 (https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-23-105861.pdf)