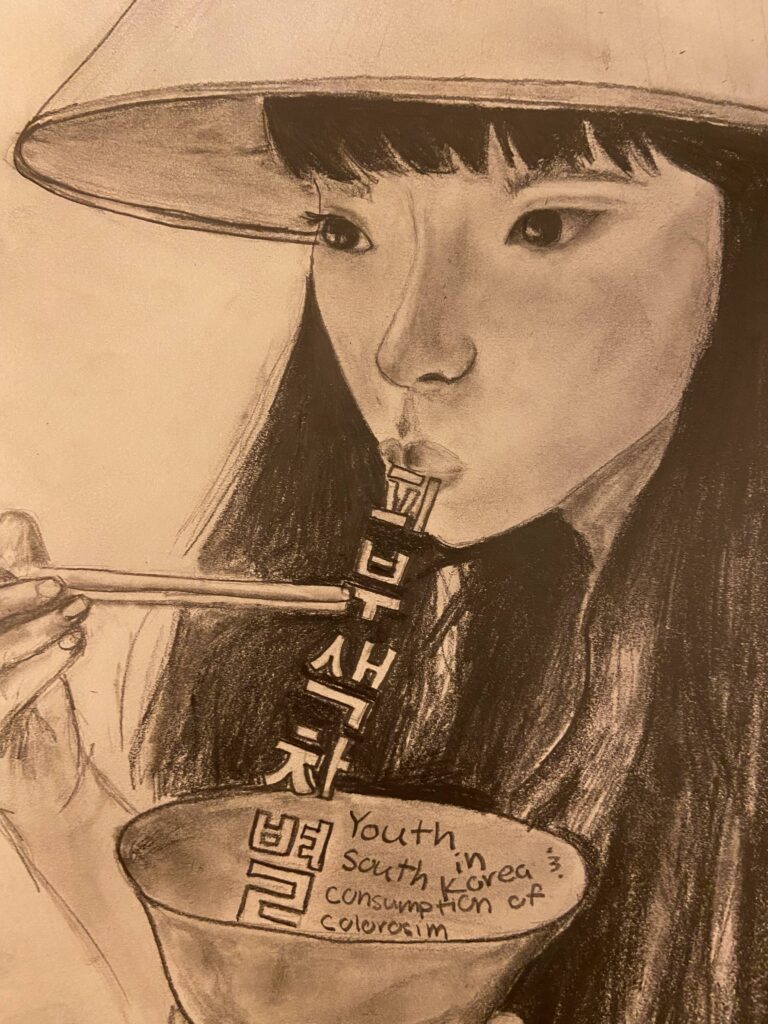

As a nine-year-old exploring the streets of Seoul, South Korea, with my family, I frequently felt the eyes of passersby follow me. During my time there, I couldn’t help but notice the long stares and occasional scrunched noses I would receive. My mother, however, who is significantly paler than I and fully Korean, would never receive uncomfortable looks from others. It wasn’t until I was much older that I came to realize that my darker complexion was isolating.

Colorism is the ideological practice of differentiating people based on the shade of their skin tone, privileging lighter skin tones. Preference for lighter skin is a large societal issue that is prevalent throughout various racial communities, especially in East Asian countries, such as South Korea. Pale skin has been a preference in Korean society since the beginning of the Gojoseon dynasty (2333-108 B.C.E) (Li 2008). During this time period, Korean citizens were categorized as either aristocrats or servants. Servants worked outside in the sun, resulting in tan darker skin, while aristocrats stayed inside wearing clothes that covered them from head to toe, maintaining their pale skin (Rondilla 2007). Korean citizens’ social status was correlated with their skin color.

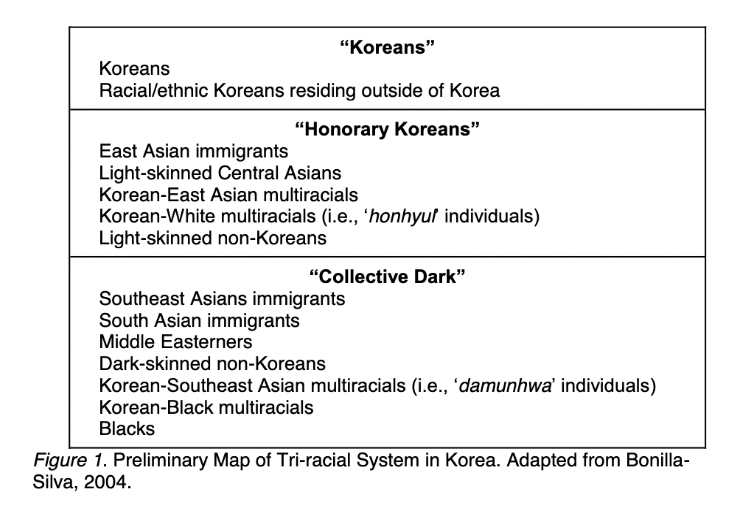

Today, Korean citizens continue to strive for a light skin standard. South Korea is extremely homogenous, with only five percent of the population being non-ethnic Korean (Shin 2021). The term, “다문하,” or “damunhwa,” identifies mixed-race Koreans as separate from fully Korean individuals. As shown in the figure below, Hyein Kim (2020) describes the racial hierarchy of South Korea.

Kim’s (2020) table illustrates the Korean racial hierarchy and its association with skin color. Despite being equally Korean, mixed Koreans of White and East Asian descent are placed higher on the hierarchy than mixed Koreans of Black and Southeast Asian descent. Darker skin is an indication of “perpetual foreignness” in Korea, a sign that one is an outsider who cannot be a “true” Korean despite one’s citizenship or Korean blood tie (Kim, 2020).

Mirrors, Textbooks, and Colorism?

The most susceptible to these issues are youth, for which colorism is an inescapable reality. From their education to the media they consume in their daily lives, colorism conditions children to negatively perceive darker skin. From the structural features of academic buildings to the images in textbooks, South Korea’s education system perpetuates colorism in youth. An English teacher in South Korea noted that there are multiple full-length mirrors in every hallway of the schools she taught at (Stone 2013). The mirrors were frequently used by both female and male students of the school and can cause children to be conscious of their skin color in schools already divided by race and ethnicity. Beyond the structural features of Korean schools, for students with multicultural backgrounds, the school dropout rate is four times higher than their fully Korean peers (Kim, 2020). Multicultural students of darker skin tones report that school bullying and harassment are major contributing factors to dropping out of school.

Prevalent images of lighter-skinned individuals in educational items sustain South Korea’s colorism. In a Korean 5th-grade social studies textbook, for example, illustrations of “foreigners enjoying Korean cultural activities” are portrayed by lighter-skinned characters, while “foreign migrant workers” are portrayed by darker-skinned characters (Kim 2020). The stereotypes represented in these textbook images are rooted in South Korea’s long history of colorism and classicism in the Gojoseon Dynasty. In all facets of a child’s educational experience in South Korea, colorism is a daunting reality.

The Hidden Truth Behind Korean Pop Culture

Hallyu, or “Korean Wave”, is the spread of South Korean culture globally since the 1990s. By increasing the production of goods and services, such as food, clothing, and of course, entertainment media, the South Korean government has ensured that Korean pop culture has caught the attention of youth across the world. Since the popularity of Elvis, the Korean government has understood and weaponized the love that teenagers have for pop idols (Adams, 2022). But underneath the surface of catchy Korean tunes are treacherous beauty standards associated with the industry. Despite their fame and popularity among the youth, Korean pop idols are not exempt from colorism. Take, for example, Kai, a member of a popular K-pop boy group, who was repeatedly teased in the media for his darker skin tone (Pham 2019). In a television segment, fellow members of the group drew Kai using a black marker to signify his tan-skinned complexion.

Kai’s experiences of prejudice, however, are not unique in the K-pop industry. Many other idols face colorism and discrimination in various ways. A person’s inability to fit into the light-skin Korean beauty standard can lead to public humiliation and damage to their self-image and esteem. Since K-pop has such a widespread audience, public displays of colorism, like the broadcast of Kai’s experience, can negatively affect how youth perceive their own skin color.

Ending the Korean Colorism Wave

Despite education and media’s capabilities to empower individuals, in South Korea’s case, these tools reinforce longstanding colorist biases. Even more concerning is that South Korea’s colorism goes beyond the borders of the country itself. South Korea has been at the forefront of global trendsetting, dictating what hair gels people use in Vietnam to what jeans are bought in China (Failoa 2006).

The history of colorism is deeply ingrained in Korean culture, even affecting Korean children whose immigrant families have chosen to leave their home country. South Korea’s prioritization of light skin influences how other countries perceive their skin color as well. Sunny Yang, a Korean American, remembers that her father used to call her “Snow White” while he would call her sister “Dark Princess”. As little children, Sunny and her sister understood that being lighter was better (Rondilla 2007).

While highly developed in its education and pop culture influence, South Korea is extremely underdeveloped in combatting colorist prejudices. Will South Korea deconstruct its colorist biases within its own country and the world? For the time being, the answer appears to be no.

Works Cited

Kim, Hyein Amber. 2020. Understanding “Koreanness”: Racial Stratification and Colorism in Korea and Implications for Korean Multicultural Education. State University of New York.

Rondilla, Joanne L., Spickard, Paul. R., & Agvateesiri, Lilynda. 2007. Is lighter better? : skin-tone discrimination among Asian Americans. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Shin Gi-Wook, March 11, 2021 “Gi-Wook Shin on Racism in South Korea” Stanford Freeman Spogli Instiate for International Studies

Li Eric , Hyun Jeong Min, Belk Russell, and Kimura Junko, Shalini Bahl (2008) ,”Skin Lightening and Beauty in Four Asian Cultures”, in NA – Advances in Consumer Research Volume 35, eds. Angela Y. Lee and Dilip Soman, Duluth, MN :

Fiola Anthony, August 31, 2006 “Japanese Women Catch the ‘Korean Wave’ Male Celebrities Just Latest Twist in Asia-Wide Craze”The Washington Post

Pham Then, 2019, “The Practice Of Racism and Colorism In South Korea Popular Media: An International Critical Race Analysis” Thammasat University

Adams Tim, September 4, 2022 “K-everything: the rise and rise of Korean culture” The Guardian