Massachusetts prides itself on being a state with one of the best public school systems in America. Yet in Boston, the state’s largest city, the education system is far from perfect. On the state mandated standardized tests this year, every single grade (3rd through 10th) had a higher percentage of students not meeting expectations in both math and English than the statewide percentage (dese 2020).

Although Boston Public Schools’ yearly budget, teaching salaries, and spending per student is much higher than its suburban counterparts, its pupils’ significantly lower academic performances are due in part to the longstanding massive racial and economic disparities in the city (dese 2020-2022). When the Boston Public School system desegregated in the 1970s, they lost a large percentage of white students whose families relocated to the suburbs or chose private schools. These racial disparities continue to affect BPS today, with 8 out of 10 students identifying as children of color (dese). This “white flight” is not just a problem in Boston, as many cities across America saw a decline in white enrollment after they desegregated their public schools. This migration of white families into the suburbs continues to make life more difficult for minorities and the low income families who stayed in the city (Frey 1979).

Boston’s loss of this higher income population led to economic deterioration that they have not ever been able to fully recover from. Many white and higher earning families still relocate from the city to the suburbs when their child turns a school-attending age. Nearly 80 percent of Boston public school students are part of low income families (Riley 2020). Students from these low income families are less likely to participate in organized activities outside of school, such as sports teams or music lessons, and have their academic skills, such as vocabulary, “cultivated” by their parents in comparison to their wealthier suburban peers (Lareau 2002). Such long-standing inequalities provoke the question of whether throwing money into the Boston Public School system is enough.

COVID’s Exacerbation of Educational Inequality

Although these educational inequalities have existed in Boston for many years, the Covid pandemic intensified them. In the past 3 years, there has been a huge decline in school enrollment and class attendance due to Covid and low socio-economic status of the students. Between 2019 and 2022, the total student enrollment in Boston Public Schools declined by around 7,000 (dese 2019-2022) and nearly a quarter of students never even logged onto the system’s remote learning offerings during the thick of the pandemic (Huffaker 2022).

Unfortunately, BPS’s attendance records did not get better when the schools returned to in person learning. Around 29 percent of students across all grades were labeled as “chronically absent” from Boston Public Schools between March 1st, 2021 and 2022, meaning they missed at least 10 percent of the school year (Huffaker 2022). With the multitude of students identifying as low income, many do not have access to the internet, stable housing, or reliable transportation to school, all of which prevents them from attending school each day (Riley 2020).

$1,300,000,000 of Hope

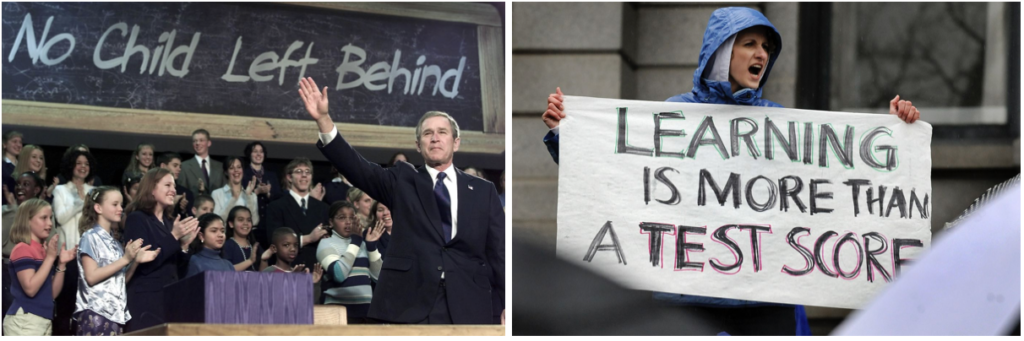

BPS has established a multitude of different programs in order to increase attendance and test scores. This year, Boston Public Schools had a $1,300,000,000 budget and vowed to spend nearly 25,000 dollars on every student in the system. They wanted to specifically devote extra resources to students with disabilities, English learners, children of color, and those suffering from poverty, which were all highlighted as problem areas in an internal review of the school system in the wake of COVID (BPS 2022). Their “National School Lunch Program” provides free breakfast and lunch to 126 different schools in the district (BPS 2020). Given many of their students face severe food insecurity, going to school could be one of the only ways for them to eat that day. The “No Child Left Behind” program aims to help students with limited English proficiency as well as their families through lessons and community events (BPS 2020). This program is offered district wide, as they found almost 60% of their students lacked English proficiency. Lastly, the “Perkins Career and Technical Education Improvement” program aims to help high schoolers from technical schools prepare for the future by teaching them skills needed for success, such as interview preparation and resume building (BPS 2020).

Will the Money Be Enough?

Unfortunately, in Boston and elsewhere, it is hard to gauge if these programs will be helpful at ending educational inequalities. There are lots of trendy fixes out there aimed to narrow education gaps, but underlying inequalities often persist. There has been some research done across different states on the efficacy of these programs, specifically the “No Child Left Behind” act and the “National School Lunch Program”.

The “No Child Left Behind” act has been criticized across many different states throughout the years for being too test focused and not addressing the underlying profound educational inequalities that cause low test performance. The program claims to focus on closing the education gap between students in poverty and their higher income counterparts, but in reality has become just another way for children to be pressured by exams, as the program’s nickname is “No Child Left Untested” (Hammond 2007).

The “National School Lunch Program” shows more positive results. Studies show that the program correlates with improved test scores and shows improvement in children’s behavior in school. There are many studies that associate hunger with decreased energy levels and agitation, so providing children with subsidized lunch helps improve their attitude and ability to focus in class (Dunifon 2003). This program has the potential to do a better job than the “No Child Left Behind” program, as it actually addresses the issue of food insecurity and how it connects to educational inequality, instead of attempting to just boost test scores (Dunifon 2003). Hopefully, with the introduction of these different programs, some of which may be more helpful than others, the city of Boston can strengthen its public education offerings and attendance records.

References

Anderson, Dan and DeCovnick, Shira. “At-Risk Level 3 Schools.” Boston, MA: Boston Public Schools. Retrieved September 28, 2022 (https://www.bostonpublicschools.org/cms/lib/MA019 06464/Centricity/Domain/162/Low%20Performing%20Schools%20deck%20for%20SC%20Updated%20911b.pdf)

Boston Public Schools (BPS). “Investing In Our Students: Fiscal Year 2022”. Boston, MA: BPS. Retrieved October 10, 2022 (https://www.bostonpublicschools.org/cms/lib/MA01906464/Centri city/Domain/184/Fiscal%20Year%202022_Boston%20Public%20Schools_web.pdf)

Chandra, Sumit, Chang, Amy, Day, Laruen, Fazlullah, Amina, Liu, Jack, McBride, Lane, Mudalige, Thisal, Weiss, Danny. “Closing the K–12 Digital Divide in The Age of Distance Learning”. Boston, MA: Broadband Communities. Retrieved October 14, 2022 (https://www.bbcmag.com/pub/doc/BBC_Nov20_DigDivide.pdf)

Darling-Hammond, Linda. “Evaluating ‘No Child Left Behind’”. The Nation. Retrieved December 3, 2022.(http://www-leland.stanford.edu/~hakuta/Courses/Ed205X%20Web site/Resources/LDH_%20Evaluating%20’No%20Child…pdf)

Dunifon, Rachel, Kowalsi-Jones, Lori. 2003. “The Influences of Participation in the National School Lunch Program and Food Insecurity on Child Well-Being”. The University of Chicago. 77(1): 1-158

Frey, William. 1979. “Central City White Flight”. American Sociological Association. 44(3): 425-448

Huffaker, Christopher. “Nearly one-third of Massachusetts students were chronically absent last year”. The Boston Globe. Retrieved October 10, 2022 (https://www.bostonglobe.com/2022/07/2 4/metro/nearly-one-third-massachusetts-students-were-chronically-absent-last-year/)

Lareau, Annette. 2002. “Invisible Inequalities: Social Class and Childrearing in Black Families and White Families”. American Sociological Association. 67(5): 747-776

Miller, Yahu. “BPS Releases 2021 Budget: Some Schools Still Facing Cuts”. Boston, MA: The Bay State Banner. Retrieved October 10, 2022 (https://www.baystatebanner.com/2020/02/10/bps-releases-2021-budget/)

Marinova, Antoniya, Schuster, Luc and Ciurcza, Peter. 2020. “Kids Today: Boston’s Declining Child Population and Its Effect on School Enrollment.” Boston, MA: The Boston Foundation. Retrieved September 28, 2022(https://media.wbur.org/wp/2020/01/Boston-Families_REV_Jan 8_44pp.pdf)

Massachusetts Department of Elementary And Secondary Education (dese). “Per Pupil Expenditures, All Funds”. Boston, MA: dese. Retrieved October 10, 2022 (https://profiles.doe.mass.edu/statereport/ppx.aspx)

Riley Jeffery C. “Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education: District Review” Malden, MA: Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education. Retrieved September 28, 2022(https://www.doe.mass.edu/accountability/district-review/default.html)

Riley Jeffery C. “Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education: Follow-Up District Review” Malden, MA: Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education. Retrieved September 28, 2022(https://www.doe.mass.edu/accountability/district-review/default.html)