The first thing that many people think of when they hear the term “accessibility” is wheelchair ramps. Ramps not only increase physical accessibility for wheelchair users, but are a convenient option for able-bodied people. Using a cart to transport something heavy? Only having stairs available will make that incredibly difficult, but with a ramp it becomes much easier. Although ramps are an incredibly simple example, they still demonstrate the value of options, specifically for members of the disabled community. When going from point A to point B, whether it is a physical or mental journey, the same path won’t be the best (or possible) route for everyone to get there.

The COVID-19 lockdown put countless people in unprecedented positions of restricted mobility. In-person interactions, our most common method for participation in daily life activities such as school and work, could no longer be the standard. As a result, other tools like remote communication (Zoom and telehealth) and use of face masks rose in prominence. Even though these changes meant hardship and inaccessibility for so many, others, especially in the disabled community, actually found their access improved (Bones and Ellison 2020; Rosenbaum, Silva, and Camden 2021; Jesus, Landry, and Jacobs 2020). As in-person interactions return, it is important to ensure that the options to use face masks and remote attendance remain.

Disability in Context

Sometimes, struggles only exist in certain environments. Take shampoo for example. Some people have naturally oily hair, while others have naturally dry and frizzy hair. If the only shampoo available is designed for oily hair, those with dry hair will struggle. If the only shampoo available is designed for dry hair, those with oily hair will struggle. When there are more options of shampoo available, neither group will struggle with their hair. Disability can be like that. Someone with dyslexia will find it much easier to read if the text is in a font designed for dyslexia. If there are ramps and elevators everywhere, a wheelchair user won’t be hindered by stairs. When only the needs of the majority are considered, when only a few paths from point A to point B are cultivated, many people end up suffering because something they cannot change causes them difficulty following those templates.

Many disabilities cannot be ‘cured’, and indeed many disabled individuals do not want to be ‘cured’, because we know that this unique piece of our identity is only seen as a detriment because it is considered ‘abnormal’. There isn’t due consideration for the strengths and perspectives our world would lose if we were ‘cured’. If the root of the matter cannot be changed, disabled individuals still live rich and fulfilling lives, and deserve the tools to pursue their goals. In our society, employment and education are closely linked to these matters, yet both fail to adequately consider the disabled population (Jesus, Landry, and Jacobs 2020).

Listening to Experience

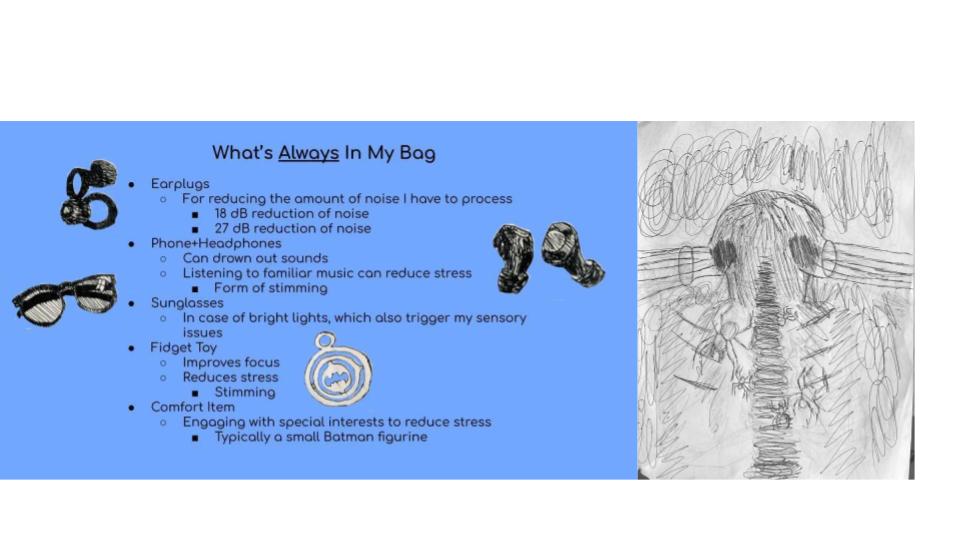

I am autistic, and one of my most prominent symptoms is sensitivity to sensory input. Anything from a scratchy shirt, strong-tasting food, a loud air conditioner, multiple overlapping voices, to countless other experiences, will trigger a stress response in my brain that will inevitably escalate to panic if exposure continues (Queensland Health 2022). Sometimes it takes more exposure, sometimes it takes less, but it has always been and will continue to be an obstacle. Almost 19 years of firsthand experience has given me an intimate understanding of my triggers, my limits, and tools that can help. I would most likely be unable to attend a residential college if I were prohibited from using an accommodation as minor as my earplugs.

The same sentiment of small changes making a big difference is often true for other disabilities, such as chronic pain or illness. We’ve spent years learning about ourselves, our strengths, and our limits. Respecting that knowledge means respecting our requests.

Remote Communication

Travel, whether it’s a regular commute or a one-off event, involves a lot of different factors for everyone, but especially for the disabled. How will you get there? When will you leave? How much extra time should, or can, you set aside for unforeseen delays? Do you have any conflicting priorities? Will your children cooperate with the plan? Will all that movement trigger a flare-up? Will you even be able to enter and navigate the building? Will you also need to secure an interpreter? For some, it becomes a fairly predictable routine where the benefits of in-person attendance vastly outweigh any of the inconveniences of travel. Others aren’t always so lucky, and many have found that using a remote option does them more good. A large part of this is the removal of the need for transportation, saving time, energy, and money (Rosenbaum et al. 2021; Bones and Ellison 2020:30). There is also increased flexibility, meaning more control over one’s schedule and surroundings (Bones and Ellison 2020:29-30; Kuznetsova and Bento 2018:34&43). With the need for a physical presence in a new space removed, the possibility of having to contend with environmental factors that you’ve eliminated or reduced at home, such as bright lights or lots of stairs, is also removed. Some families with disabled members found it easier to integrate the skills and lessons learned in therapy into home life when they were being developed right there, instead of in an office (Rosenbaum, Silva, and Camden 2021). The most clear benefit of remote attendance options falls to people who are immunocompromised. They can participate in events without risking their health or life by being exposed to a large group (Nowakowski 2023:16-17)

Face Masks

Face masks function by stopping the majority of particles expelled from the nose and mouth from dispersing in the air, reducing the chances of transmission for any illness that spreads via those particles. Though they’ve been popularized in recent years specifically for COVID-19 spread prevention, they are also effective against influenza, colds, and, once again, any other illness that can spread via particles expelled from the nose and mouth. The CDC still recommends face masks “in indoor areas of public transportation and transportation hubs” (CDC 2022), and adhering to this, as well as wearing a mask in other public spaces when ill, is a way to help keep immunocompromised individuals safe from otherwise avoidable threats.

If face masks remain as a normalized part of our culture, it can also reduce stress on those who would wear them before the pandemic (Nowakowski 2023:21) or will continue the practice. I, and others in the autistic community, have come to value the energy we can save when we don’t have to worry about the expression on the lower half of our faces. It’s comforting to know that if I’m feeling drained or anxious, I can put on a face mask and only worry about replicating eye-related social queues without prying questions about my choice. *

Wrap-Up

As the world continues to move away from mandatory social distancing, it’s important to be aware of other perspectives and needs. Maintaining the normalization of using remote communication and masks will specifically benefit many members of the disabled community, as well as anyone else who may find convenience in having another option available.

*Footnote: I do also recognize that face masks can be harmful to the access of deaf and hard of hearing individuals, and would also like to add that this is an issue that can be addressed through awareness and AAC (augmentative and alternative communication, which refers to any form of communication besides talking)

References

Barden, Owen., Ana Bê, Erin Pritchard, and Laura Waite. 2023. “Disability and Social Inclusion: Lessons From the Pandemic.” Social Inclusion 11(1):1-4. Retrieved March 27, 2023 (https://www.proquest.com/socabs/docview/2776046067/fulltextPDF/EAD7845DF86B4B51PQ/1?accountid=11264)

Bones, Paul D. C., and Vanessa Ellison. 2022. “The “New Normal” for Disabled Students: Access, Inclusion, and COVID-19.” Sociation 21(1):21-40. Retrieved March 27, 2023 (https://sociation.ncsociologyassoc.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/newnormal_proof_bones.pdf)

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2023. “How to Protect Yourself and Others.” Retrieved March 28, 2023 (https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/prevention.html)

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2022. “Wearing Masks in Travel and Public Transportation Settings.” Retrieved March 28, 2023 (https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/travelers/masks-public-transportation.html#Frequently-Asked-Questions)

Jesus, Tiago S., Michel D. Landry, and Karen Jacobs. 2020 “A ‘new normal’ following COVID-19 and the economic crisis: Using systems thinking to identify challenges and opportunities in disability, telework, and rehabilitation.” Work 67(1):37-46. Retrieved March 27, 2023 (https://content.iospress.com/articles/work/wor203250)

Kuznetsova, Yuliya., and João Paulo Cerdeira Bento. 2018. “Workplace Adaptations Promoting Inclusion of Persons with Disabilities in Mainstream Employment: A Case-Study on Employers’ Responses in Norway.” Social Inclusion 6(2):34-45. Retrieved March 17, 2023 (https://www.proquest.com/socabs/docview/2089850303/ACB1516534934A06PQ/10?parentSessionId=GASlzjZMGjkShVo5VXb6Q9m2jd7U8T%2BsPlGi%2FZdmo6Y%3D)

Miserandio, Christine 2008. “The Spoon Theory.” Retrieved March 28, 2023 (https://butyoudontlooksick.com/articles/written-by-christine/the-spoon-theory/)

Nowakowski, Alexandra “Xan” C. H. 2023. “Same Old New Normal: The Ableist Fallacy of “Post-Pandemic” Work.” Social Inclusion 11(1):16-25. Retrieved March 27, 2023 (https://www.proquest.com/socabs/docview/2776046910/454DB23168E04AC9PQ/34)

Queensland Health 2022. “Sensory overload is real and can affect any combination of the body’s five senses: learn ways to deal with it.” Queensland Government. Retrieved March 28, 2023 (https://www.health.qld.gov.au/news-events/news/sensory-overload-is-real-and-can-affect-any-combination-of-the-bodys-five-senses-learn-ways-to-deal-with-it#:~:text=In%20addition%20to%20the%20above,physical%20discomfort)

Rosenbaum, Peter L., Mindy Silva, and Chantal Camden. 2021. “Let’s not go back to ‘normal’! Lessons from COVID-19 for professionals working in childhood disability.” Disability and Rehabilitation 43(7):1022-1028. Retrieved March 27, 2023 (https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/09638288.2020.1862925)

Xiao, Junhong “Frank”. 2021. “From Equality to Equity to Justice: Should Online Education Be the New Normal in Education?” Handbook of Research on Emerging Pedagogies for the Future of Education: Trauma-Informed, Care, and Pandemic Pedagogy 1:1-15. Retrieved March 27, 2023 (https://www.researchgate.net/publication/350990790_From_Equality_to_Equity_to_Justice_Should_Online_Education_Be_the_New_Normal_in_Education)