The lack of diversity is a major problem in most spaces and institutions within the United States, but it is especially prevalent within the outdoor industry, which is dominated by wealthy white people. In 2015, people of color, who comprise 40% of the U.S. population, only accounted for about 20% of the visitors to national parks.1

Wilderness as a historically white space

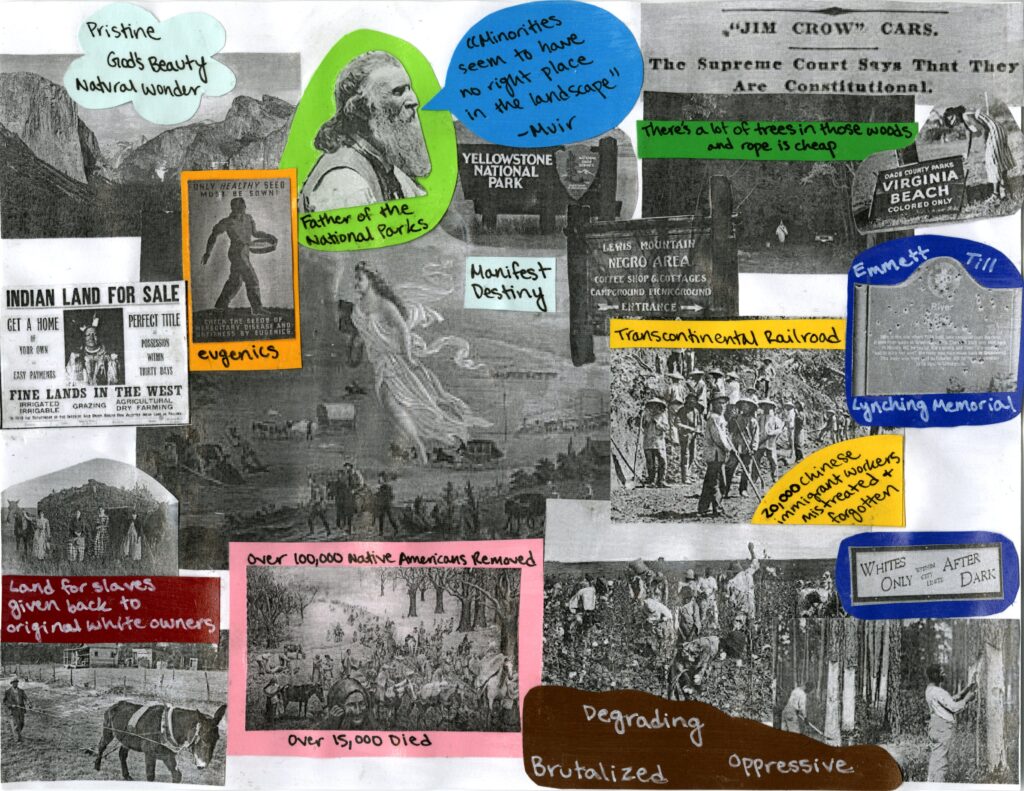

Countless racist policies in the history of the U.S. excluded racial minorities from the outdoors in varying ways, making the outdoors into a predominantly white space.

The forced relocation of Native Americans from their land, exemplified by the Indian Removal Act of 1830 and the subsequent Trail of Tears, opened the land for the settlement and use by white people.2 This westward expansion both helped privatize land for white people’s economic growth and allowed them access to and the ability to protect the great “untouched” beauty they “discovered” in the west.3 The National Parks were created by conservationists who supported eugenics and believed nature was for the enjoyment of the white aristocracy while racial minorities had no real place in the landscape.4

The National Parks enforced these racist ideals through Jim Crow Laws that segregated the spaces by not allowing white and Black visitors to use the same campgrounds, picnic areas, and other facilities.5 Given the history of lynchings in forests, which often occurred in rural, white areas across the U.S., people of color fear the unknowns of nature and thus avoid engaging with it.6

White portrayal of the outdoors

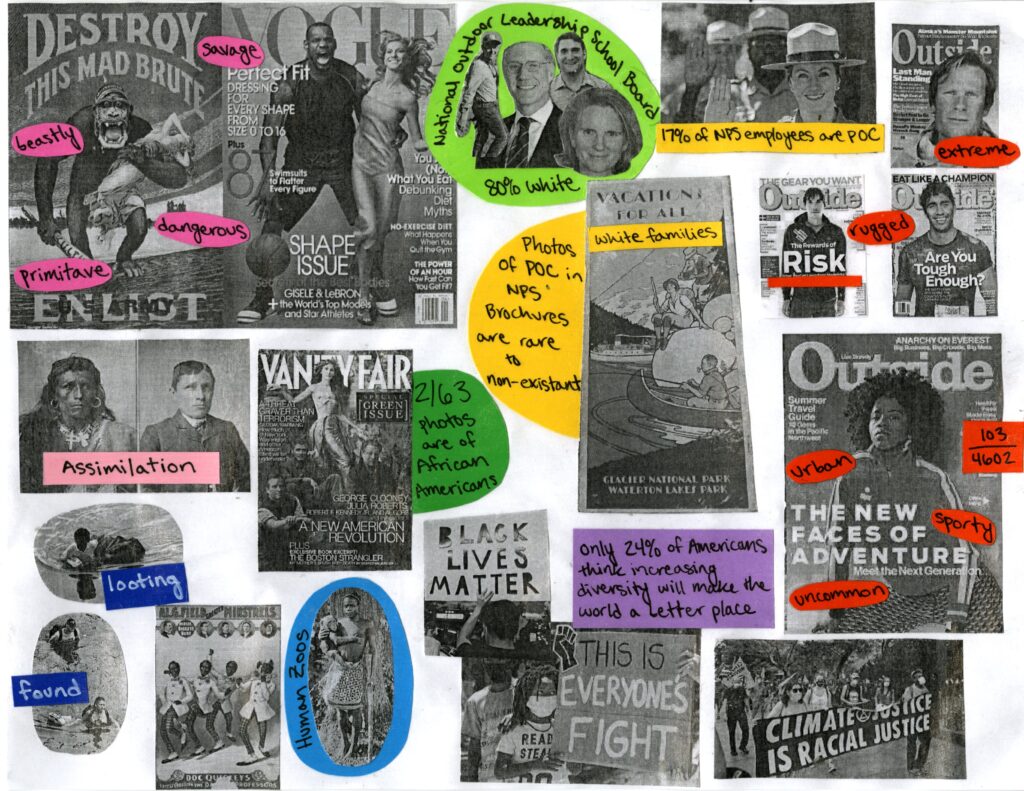

The majority white workforce at various outdoor organizations means the people of color are not included in decision making processes. Only 17% of NPS employees and 20% of the board at the National Outdoor Leadership School are people of color.7,8 Even when minorities are included in discussions about race, their ideas are often denied, which simply worsens the inequality.9

People of color are severely underrepresented in the National Park brochures.10 Another study found that 100% of National Park visitors failed to learn new information about the racialized history of the land due to the park’s avoidance of their colonial past.11

A prominent outdoors publication, Outside magazine, also underrepresents people of color. Within 44 issues, only 103 of the 4,602 pictures of people were of people of color (2.2%) and the majority of these 103 pictures were of famous male sports figures in urban settings.12 Lack of representation and racist stereotypes about minorities lead to the internalization of these negative beliefs.13 Without proper representation minorities do not know about all of the opportunities in the outdoors that they could experience.

White environmentalism as a form of exclusion

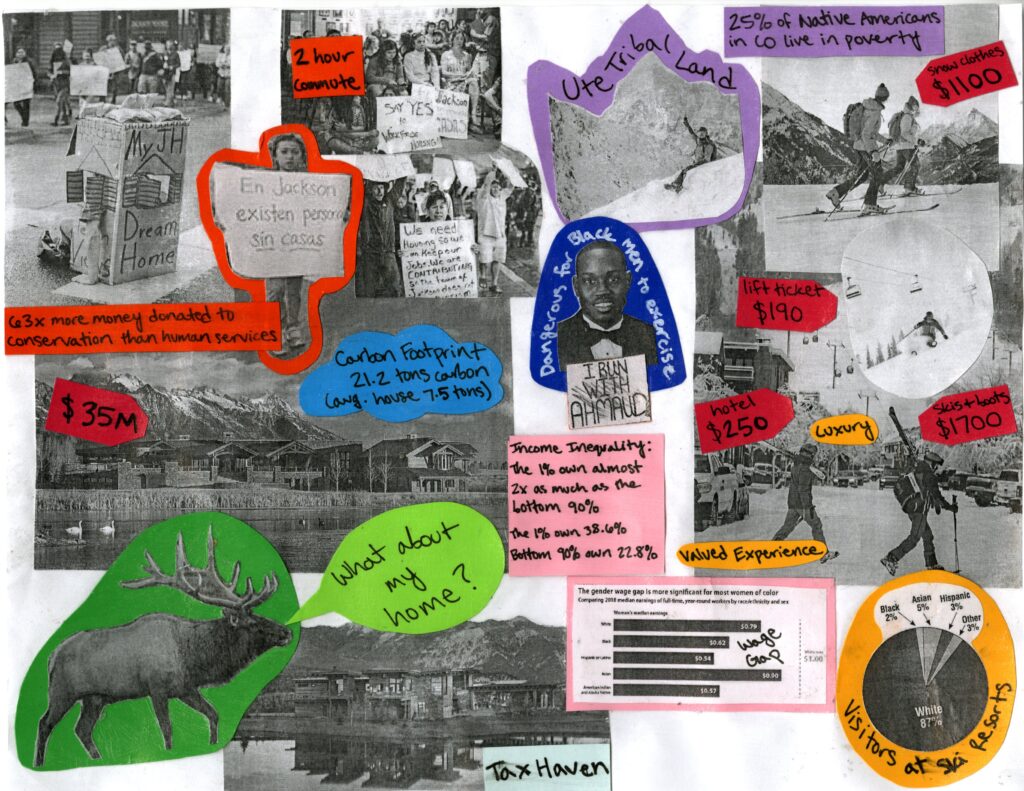

White, wealthy people continue to exclude people of color from the spaces they deem valuable. Often people assume the high cost of participating in outdoor activities excludes people of color since they make ten cents less per dollar compared to white people, however, the problem is much larger than that.14

The ultra-wealthy further contribute directly to the exclusion of minorities when they support conservation efforts in order to preserve land for their own personal use and enjoyment, just like the founders of the National Parks.15 Increased conservation decreases the amount of land available for housing. As land becomes a scarce resource, the cost of living increases.16 The working class, which consists of many people of color, are forced to relocate because they can no longer afford the housing costs. For example, in Teton County, many employees of wealthy homeowners and services often have to commute two hours to work all while working for the ultra wealthy for less than living wages.17

Although the ultra-wealthy view their conservation donations as altruistic, their conservations efforts come with benefits, such as elite networks and tax breaks.18 Additionally, their homes have large carbon footprints and may obstruct wildlife habitat.19 The contradictory actions of the ultra-wealthy continue a long legacy of white wealthy Americans’ enjoyment of natural land, to the detriment of other people who reside on it.

Citations

1 Rott, N. (2016, March 9). Don’t Care About National Parks? The Park Service Needs You To. National Public Radio. https://www.npr.org/2016/03/09/463851006/dont-care-about-national-parks-the-park-service-needs-you-to.

2, 3, 6, 9-13 Finney, C. (2014). Black Faces, White Spaces: Reimagining the Relationship ofAfrican Americans to the Great Outdoors. The University of North Carolina Press.

4 Jacobs, J., & Hotakainen, R. (2020, June 25). Racist roots, Lack of Diversity Haunt NationalParks. E&E News. https://www.eenews.net/stories/1063447583.

5 Repanshek , K. (2019, August 18). How The National Park Service Grappled With Segregation During The 20th Century. National Parks Traveler. https://www.nationalparkstraveler.org/2019/08/how-national-park-service-grappled-segregation-during-20th-century.

7 Sonken, L. (2020, July 5). National Park Service Continues To Grapple With Diversity In Workforce. National Parks Traveler. https://www.nationalparkstraveler.org/2020/07/national -park -service-continues-grapple-diversity-workforce.

8 NOLS. (2021). Our Team. NOLS. https://www.nols.edu/en/about/our-team/.

14 Miller, S. (2020, June 11). Black Workers Still Earn Less than Their White Counterparts. Society for Human Resource Management. https://www.shrm.org/resourcesandtools/hr-topics/compensation/pages/racial-wage-ga ps-persistence-poses-challenge.aspx.

15-19 Farrell, J. (2020). Billionaire Wilderness: The Ultra-Wealthy and the Remaking of the American West. Princeton University Press.