Predominantly white colleges and universities tend to overrepresent people of color (POC) on their official websites in their efforts to portray a welcoming environment for POC on campus. The websites show professors of color excitedly giving speeches to the campus community, talking happily with other colleagues, or working collaboratively with students in labs. Universities’ official websites fail to acknowledge the challenges many POC faculty have to face in PWIs. While working at PWIs, POC professors all too often face challenges coming due to underrepresentation, tokenism, and interpersonal and institutional racism.

Underrepresentation and Tokenism

POC are an underrepresented but growing proportion of faculty in predominantly white colleges and universities. In 2015, ~20% of all full-time postsecondary faculty were POC (National Center for Education Statistics 2015). By 2020, ~26% of all full-time postsecondary faculty were POC (National Center for Education Statistics 2020). Compared to the statistics in 2015, there is a considerable increase in the percentage of POC in full-time postsecondary faculty. Although there are increases in the proportion of POC in higher education, the proportion of Black and Hispanic groups in higher education are less than would be expected given their proportion of the US population.

| Race | % among full-time postsecondary faculty in US (National Center for Education Statistics 2020) | % among US population (US Census Bureau 2020) |

| Asian/Pacific Islanders | 12% | 6% |

| Black | 7% | 12% |

| Hispanic | 6% | 19% |

| American Indian/ Alaska Native/ Multirace | 1% | 1% |

Tied to the underrepresentation of POC in higher education is institutional racism. Institutional racism is commonly entrenched in an institution’s history and is systemic and part of habitual operating procedures (Stanley 2006). Predominantly white educational institutions operate as racialized organizations, creating inequalities in access to resources based on race and social class of students and professors. For instance, in high schools, Black and Latinx students are more likely to be tracked into “basic” courses, while white and Asian high school students are more likely to be given the opportunity of attending AP and honors courses (Stewart 2021). This contributes to the unequal starting points if and when these differentially tracked students enter college. Similarly, in PWIs, institutional racism also appears in the way that POC faculty face lack of support from the department or administrators of the institutions. The situation is especially risky for POC faculty who are on the tenure track but have not yet received tenure, since they may experience receiving biased evaluations from students, other faculty, and administrators of the institution based on their race and ethnic background. POC faculty may experience having unclear information about funding opportunities and promotion standards (Reddick et al. 2021).

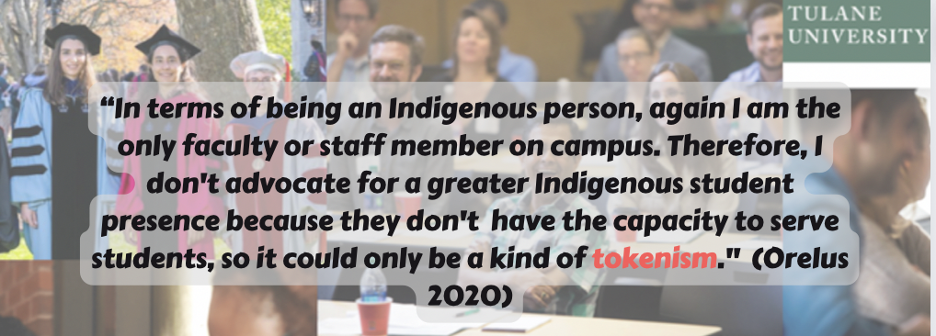

Some professors of color report being perceived and treated as tokens. “Tokens” refers to numerically minorities as opposed to a dominant majority (Kanter 1977: 965). When POC faculty arrive on campus, they may find that their colleagues and students treat them as if they were hired to increase the “diversity” of the universities rather than due to their accomplishments and expertise. For instance, they tend to be asked to make speeches on diversity, equity, and inclusion issues to the campus community. Campus newsletter or official Instagram posts are then able to include such activities that demonstrate the increase in “diversity” of the campus in their publications. This portrays such campuses as a welcoming environment for professors of color to people from outside of the campus community. However, events of this kind do not delve into the actual challenges POC on campus face, such as microaggressions or systemic inequities (Orelus 2020).

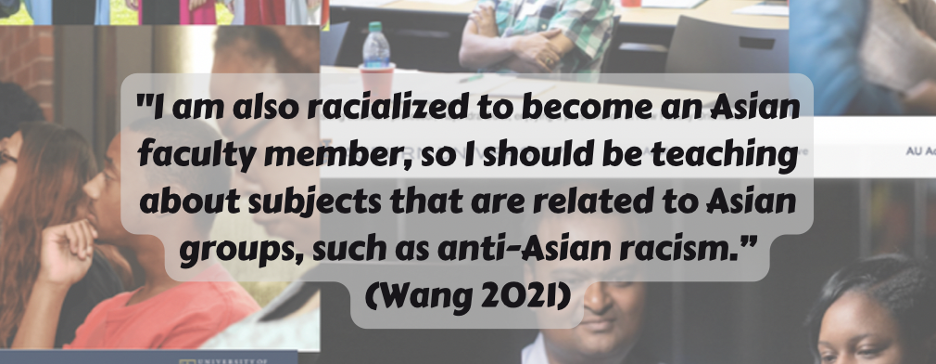

Moreover, professors of color are tokenized as being responsible for providing knowledge about their ethnic groups at PWIs. They are perceived as being “Other” from the lens of White majority culture, and they are considered an expert of their own culture (Wang 2021). POC in PWIs are considered as a resource that benefits all the students in learning about diversity related issues as well. For instance, a professor who was born in China reports being expected to teach about ‘global’ subjects and topics related to Asian groups, such as anti-Asian racism, even if her subject expertise is far afield of such content (Wang 2021).

Tokenism is one of the ways that interpersonal racism in higher education manifests. Interpersonal racism refers to the racism happening between individuals. In higher ed, interpersonal racism can be demonstrated in ways like POC professors not being valued for their opinions or scholarship (Stanley 2006). For example, interpersonal racism may occur if a student’s parent questions a POC faculty’s academic credentials in relation to a certain grade she has given. Foreign-born faculty of color comprise a particularly vulnerable group in relation to interpersonal racism when teaching in PWIs. Foreign-born professors are likely to be considered as being immigrants, as foreign, and as ethnic from the lens of the White majority (Wang 2021). Immigrant professors of color who speak English with a distinct accent are additionally likely to face racial and linguistic profiling, which refers to the action of using auditory cues in identifying social characteristics of a person (Orelus 2020).

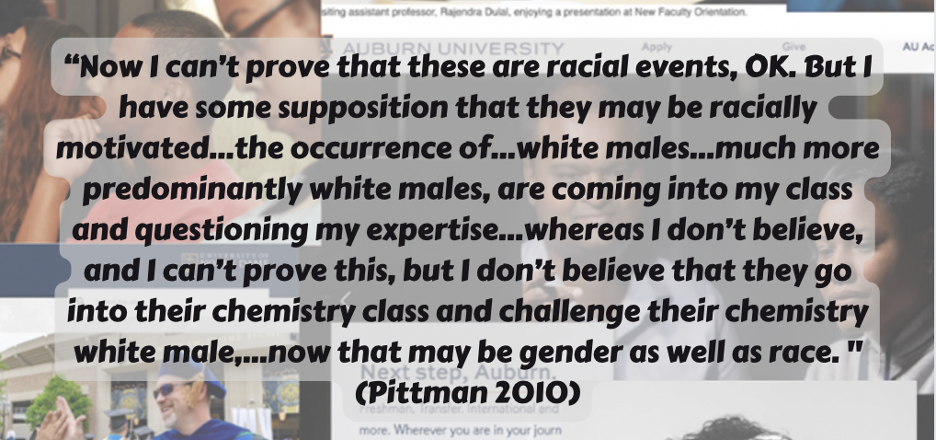

Experiences of interpersonal racism and tokenism are especially visible among female faculty of color. Many female professors of color experience being tokenized and stereotyped by colleagues and students. For instance, black female faculty have to negotiate the mothering-yet-obedient “mammy” stereotype, and Asian American professors have to grapple with the stereotype of being passive (Pittman 2010). Female faculty of color also may have to contend that they are hired because of affirmative action and associate with colleagues’ assumptions that they are not legitimate scholars and professors (Pittman 2010). Furthermore, female professors of color also experience structural inequality in interpersonal interactions with a majority of white students in the classroom environment, rooted in unequal dynamics due to the race and gender within the classroom setting. Women faculty’s description of classroom interactions with white male students as congruent with gendered racism elsewhere in higher education and U.S. society (Pittman 2010). In Professor of Sociology Ginger Ko’s experiences teaching social justice as a woman of color in a predominantly white institution, she reports consciously giving up her authority in the classroom because of her positionality as a young woman of color in the face of student pressure (Ko 2015).

Calling for Action in Higher Ed

Though the proportion of POC faculty in higher education has been increasing over the past decades, higher ed should shift their focus more to the actual experiences of POC faculty. Tokenism of professors of color exists in PWIs but is all too often invisible without hearing from POC faculty of their experiences. The tokenism experienced by POC faculty treated as representing “diversity” devalues their authority as scholars. More discussions on the issue of tokenism in higher-ed are essential to better understand the experiences of POC faculty. For instance, universities and colleges should build platforms for professors to comfortably share their feelings and suggestions for change being part of the campus community, while making sure their opinions are heard and changes are ready to be made.

References

Jones, Nicholas, Nicholas Jones, Rachel Marks, Roberto Ramirez and Merarys Rios-Vargas.

2021. “2020 Census Illuminates Racial and Ethnic Composition of the Country.” United

States Census Bureau.

(https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/08/improved-race-ethnicity-measures-revea

l-united-states-population-much-more-multiracial.html)

Kanter, Rose Moss. 1977. “Some Effects of Proportions on Group Life: Skewed Sex Ratios and Responses to

Token Women.” American Journal of Sociology, 82(5), 965–990.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/2777808

Ko, Ginger. 2015. “The Case for Humanities Training: A Woman of Color Teaching Social Justice in a

Predominantly White Institution.” Theory in Action 8(4):55-65

(https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/case-humanities-training-woman-color-teaching/

National Center for Education Statistics. 2022. “Characteristics of Postsecondary Faculty.” Condition of

Education. U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences. Retrieved May 31,

2022, from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/csc.docview/1732611986/se-2). doi:

https://doi.org/10.3798/tia.1937-0237.15023.

Orelus, Pierre W. 2018. “Can Subaltern Professors Speak?: Examining Micro-Aggressions and Lack of

Inclusion in the Academy.” Qualitative Research Journal 18(2):169-179

(https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/can-subaltern-professors-speak-examining-micro

/docview/2036686730/se-2). doi: https://doi.org/10.1108/QRJ-D-17-00057.

Pittman, Chavella T. 2010. “Race and Gender Oppression in the Classroom: The Experiences of

Women Faculty of Color with White Male Students.” Teaching Sociology 38(3):183-196

(https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/race-gender-oppression-classroom-experiences/d

ocview/907548010/se-2).

Reddick, Richard J., Betty J. Taylor, Nagbe Mariama and Z. W. Taylor. 2021. “Professor Beware:

Liberating Faculty Voices of Color Working in Predominantly White Institutions and

Geographic Settings.” Education and Urban Society 53(5):536-560

(https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/professor-beware-liberating-faculty-voices-color

/docview/2524143091/se-2). doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0013124520933349.

Stanley, Christine A. 2006. “Coloring the Academic Landscape: Faculty of Color Breaking the

Silence in Predominantly White Colleges and Universities.” American Educational Research Journal 43, no. 4: 701–36. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312043004701.

Stewart, Mahala Dyer, Ashley García, and Hannah Petersen. 2021. “Schools as Racialized

Organizations in Policy and Practice.” Sociology Compass 15(12).

Wang, C. 2021. “The irony of an `international faculty’ Reflections on the diversity and inclusion

discourse in predominantly White institutions in the United States.” Learning and Teaching,

14(2), 32–54. https://doi.org/10.3167/latiss.2021.140203