When you think about sports, specifically team sports, you don’t instinctively focus on the background of the players. Growing up, I was the only Black player on my varsity soccer team, and I was one out of the 5 Black players on my varsity lacrosse team. I was fortunate enough to attend a private school that provided many resources dedicated to sports to provide the best experience possible.

Many people that share my background do not have these same opportunities. In 2022, Black student-athletes made up only 16% of the NCAA student-athlete population (Siskind 2023).

While there are advantages to playing sports such as opportunities for college recruitment, personal development and overall mental well being, many Black youth are unable to access these benefits of playing sports (Hiremath 2019). This lack of accessibility begins early on. As a result, Black athletes lose many opportunities, and their mental health can suffer in the process (Hiremath 2019).

Pay to Play

Because entry-level sports are expensive, many working class families lack the time and money to introduce their kids to sports. In 2021 the average cost of a single child’s primary sport for one season amounted to $833 (Aspen Institute 2022).

This lack of exposure can initiate cycles of limited access to resources and opportunities for physical activity among Black youth, widening existing disparities in athletic participation and development.

Sports also require a significant time commitment from parents and their ability to transport their children to practice, games, tournaments and other related events which working class families may be unable to do. As one parent explained:

“My kid loves soccer, and I want her to have an opportunity to play through high school. For that to happen, I have to start her in travel soccer in third grade, because all the other kids trying out for the high school team will have started travel soccer in third grade. But travel soccer costs thousands of dollars a year, my child is exhausted and traveling to games almost every weekend is putting strain on my other kids. Don’t even get me started about schlepping to practices all week long (Grose 2024).”

It’s unfortunate that pursuing youth sports is such a costly commitment and strain on parents and family life. Without access to sports early on, when entering high school, working class Black students have less experience with sports and have less time to develop and showcase their potential for collegiate and higher level play.

Resource Discrepancies in Poorly Funded Public Schools

Athletes’ experiences at less resourced public schools are significantly different from the experiences of athletes at well-resourced schools. Working class families send their children to schools in low income communities that lack resources for athletics (Aspen Institute 2022).

Rahway High school and Roosevelt School are public schools located in NJ, both display their lack of resources and space. The space in the first image shown doubles as an auditorium.

In contrast, children from higher-income families can access private schools with robust athletic programs and better facilities. This discrepancy further increases the gap in sports participation and development between students from low-income and high-income backgrounds.

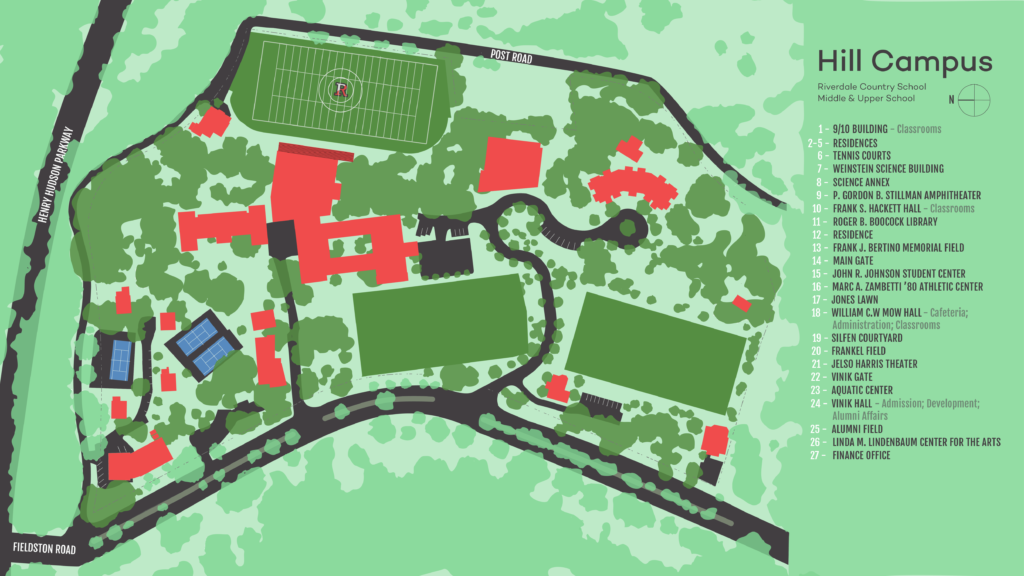

For example, my high school, Riverdale Country School, consistently secures top rankings in the New York City metro area, as recognized by sources like Niche, Bronx Times and U.S News and World Report. Riverdale Country School tuition is roughly $65,000 and increasing every year.

Riverdale continuously prioritizes the renewal and enhancement of its athletic facilities, ensuring students have access to cutting-edge amenities. Through my time at Riverdale, for example, they replaced all gym equipment and even built a new varsity swimming facility with a new pool and locker rooms. This surplus of resources dedicated to athletics highlights a larger issue; students attending high-income private schools, like Riverdale, enjoy significantly more opportunities for personal growth, skill development, and recognition within the realm of sports. The imbalance in resources feeds into unequal opportunities for athletic success and recognition among students from varying socioeconomic backgrounds.

Sports’ Effects on Mental Health

Participation in sports has been shown to yield many mental health benefits for children and adolescents. Active involvement in sports fosters a more positive attitude towards life and reduces thoughts of suicide (Taliaferro et al. 2011). Additionally, research demonstrates that sports participation enhances self-control, confidence, and reduces social anxiety, highlighting the psychological advantages of engaging in sports (Holt et al. 2011).

Given these benefits, sports can help reduce symptoms of mental illness. This is especially important because Black students have been shown to struggle with a higher prevalence of major mental health concerns ranging from a anxiety to suicide, compared to white students overall (Hiremath 2019).

Athletes’ experiences on sports teams can significantly impact their mental health. While participation in sports and being part of a team can positively influence one’s mental well-being, it can also exacerbate feelings of isolation, especially for individuals who do not share a common identity (Merkel 2013). People of color often experience a strong sense of “otherness” on sports teams, leading to feelings of isolation and making it challenging to connect with teammates off the field (Hiremath 2019). For example, in my experience, I often felt isolated from my teammates and found it easier to be more reserved, making less effort to interact with them outside of practice or games.

Working class Black students students can miss out on the social interactions, stress relief, and sense of achievement that sports provide. This can contribute to higher levels of stress, anxiety, and depression which are issues that Black working class students may already struggle with (Mueller et al. 2003). If public sports programs had more resources, working class students might reap more of the benefits that come with participating in them.

Moving Forward

Student athletes’ experiences in high school matter because it is one of the best ways to showcase their potential for college recruitment, opening many opportunities for their future. College recruitment is one of the best ways to overcome the financial barriers many Black families have in education. Yet the students who would benefit the most from recruitment often have the least access to the necessary resources such as updated equipment, adequate coaching staffs and other external resources for recognition and development.

Improving the quality of high school sports for Black students can significantly change their futures. School sports should nurture students’ development, regardless of their families’ background.

There are many ways to improve access to and students’ experiences in athletic programs. Increasing state funding for sports programs in underfunded schools can provide adequate resources for equipment, coaching staff, and facility maintenance. Some state sports associations have made efforts to fund high school athletic programs. For example, the New York’s high school athletic association is currently partnering with a running company to donate over 1 million dollars worth of gear by the end of 2024 (NYSPHSAA 2024). Additionally, partnerships with community organizations, local businesses, and sports leagues can offer financial support, volunteer coaches, and access to facilities.

Introducing after-school sports programs and intramural leagues can also provide opportunities for students to participate in sports, regardless of their economic background, promoting physical activity and fostering a sense of teamwork and camaraderie. Finally, advocating for policies that prioritize equitable distribution of resources and opportunities in education, including sports, can help address systemic inequalities and ensure that all students regardless of their background have access to quality athletic programs.

References

Anon. 2024. “New York State Public High School Athletic Association.” Grants – New York State Public High School Athletic Association. Retrieved April 24, 2024 (https://nysphsaa.org/sports/2023/4/21/Foundation_Grants.aspx).

Grose, Jessica. 2024. “Why so Many Kids Are Priced out of Youth Sports.” The New York Times. Retrieved April 2, 2024 (https://www.nytimes.com/2024/02/14/opinion/youth-sports.html).

Hiremath, Chandrakanta. 2019. “Impact of Sports on Mental Health.” Journalofsports. Retrieved April 10, 2024 (https://www.journalofsports.com/pdf/2019/vol4issue1S/PartA/SP-4-1-4-781.pdf).

Holt, Nicholas L., Bethan C. Kingsley, Lisa N. Tink, and Jay Scherer. 2011. “Benefits and Challenges Associated with Sport Participation by Children and Parents from Low-Income Families.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 12(5):490–99.

Merkel, Donna L. 2013. “Youth Sport: Positive and Negative Impact on Young Athletes.” Open Access Journal of Sports Medicine. Retrieved March 29, 2024 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3871410/#sec-a.m.ctitle).

Mueller, Florian, Stefan Agamanolis, and Rosalind Picard. 2003. “Exertion Interfaces.” Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems.

NCAA.org. 2023. “What Black History Month Means to Those in Athletics.” NCAA.Org. Retrieved March 8, 2024 (https://www.ncaa.org/news/2023/2/17/media-center-what-black-history-month-means-to-those-in-athletics.aspx#:~:text=According%20to%20the%20NCAA%20demographics,colleges%20and%20universities%20as%20members).

Pandya, Nirav Kiritkumar. 2021. “Disparities in Youth Sports and Barriers to Participation.” Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine 14(6):441–46.

Taliaferro LA;Eisenberg ME;Johnson KE;Nelson TF;Neumark-Sztainer D; 2011. “Sport Participation during Adolescence and Suicide Ideation and Attempts.” International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health. Retrieved April 13, 2024 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21721357/).