Dodging Overpopulation: Are We Truly Safe?

People across the globe have long feared overpopulation and its detrimental effects on our planet, such as overconsumption, pollution and climate change. But, what many fail to realize is that in certain developed countries, the opposite trend is occurring. In the United Kingdom, Japan, and other Western European countries, birth rates are on the decline (Nargund 2009). Unfortunately, a dwindling population comes with a barrage of consequences. As Japan currently undergoes this transformation, it can provide valuable insight into the challenges other nations may face in the coming decades.

Taking a closer look at Japan

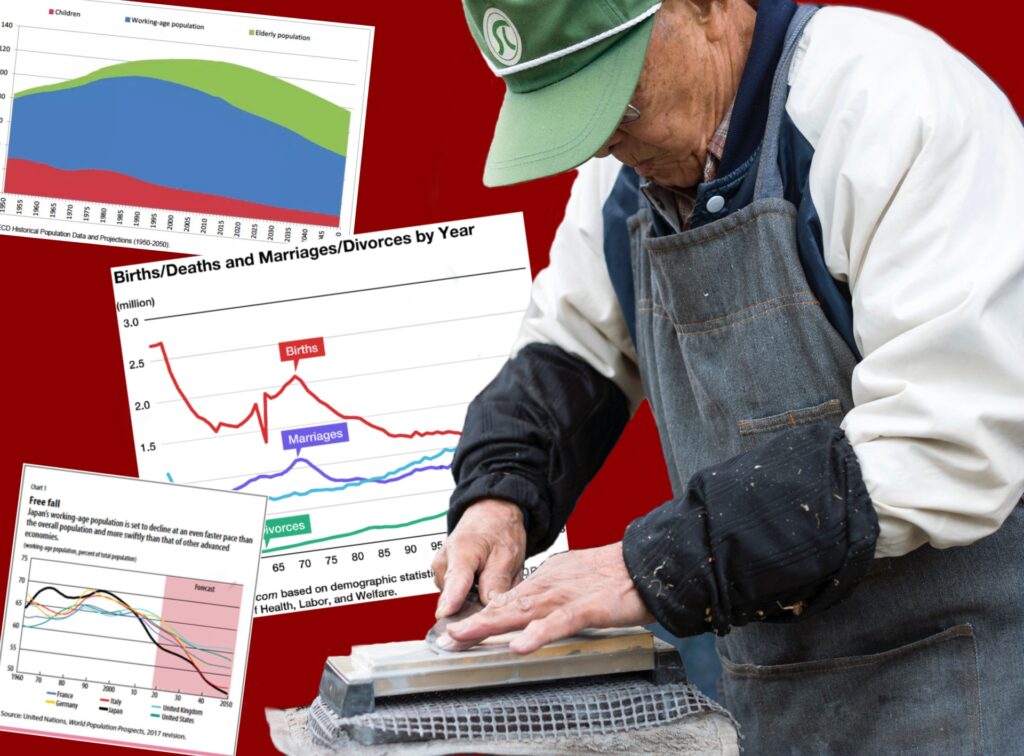

Why are fewer Japanese people being born? A combination of factors including financial insecurity and decreasing marriage/fertility rates are causing Japanese birth rates to plummet (Iijima et al. 2018). Generally, later marriages and high education/housing costs are commonly cited explanations for the decreasing marriage rate, which is related directly to birth rates (Ueno 1998). Japan also possesses an unusually large number of working-class elderly people (Moriyama 2022). Experts project that these characteristics will lead to Japan having roughly one elderly person for every two people of working age by 2025, the highest old-age dependency ratio of any major industrialized nation (Muhleisen et al. 2001). But what does this mean for their future?

Economic Implications

An aging population will unquestionably strain the Japanese economy, most simply due to the smaller number of children who will grow up and enter the workforce. A smaller workforce will lead to less economic growth and output, ultimately decreasing Japan’s real gross domestic product (Muhleisen et al. 2001). A decreased GDP often causes people to lose their jobs, which can ruin lives and make GDP losses harder to recover (Callen 2024). More than that, Japan’s economy has already been struggling for decades, and even narrowly avoided a recession in 2023 (Wolf 2024). Some believe if these issues are not addressed, the coming years could be catastrophic for millions of people.

Impacts on the Elderly

Another important angle to consider is the effect Japan’s aging population has on its elderly citizens, compelling many of them to re-enter the workforce (Moriyama 2022). Generally speaking, Japanese people are highly motivated to work: a 2019 survey of Japanese men and women in their 60s found that the most common response when asked about their retirement age was “Want to work as long as possible, regardless of age” (Moriyama 2022). While some of these respondents are working voluntarily, having no other choice but to continue working is also a driving factor for many of them: roughly 3 in 4 respondents in the same survey reported “economic reasons” as a relevant factor when asked why they were still working (Moriyama 2022). In addition, a different 2019 survey of Japanese men and women aged 50-74 found that working has negative impacts on anxiety and life satisfaction (Katagiri 2023).

What is currently being done to address the issues?

Ultimately, the point here is clear: the demographic shifts Japan is experiencing negatively impact the lives of its elderly citizens and threaten the country’s economic security. In the decades to come, Japan is expected to continue on the same trajectory, currently projected to lose tens of millions of working people by 2040, continue experiencing falling fertility rates, and have over 37% elderly citizens in their population by 2050 (Moriyama 2022).

The current situation commands intervention. Unfortunately, it’s difficult to address both aspects of the issue simultaneously.

In the early 2000s, the Japanese government passed legislation that slashed pension benefits for future retirees and increased the age of eligibility for earnings-related pension payments from 60 to 65 (Muhleisen et al. 2001). Both of these changes present economic challenges to the elderly with the hope of helping the overall economy recover.

Today, the Japanese government has increased its child allowance and financial aid for young couples in an attempt to bring birth rates back up (Urata 2024). However, it may be too little too late.

What can other countries learn from Japan?

Once a country begins this demographic transition, it can be difficult to stop. The problems caused by falling birth rates, including fear of a recession or falling unemployment, create even more anxiety around having children (Iijima et al. 2018). This means a vicious cycle can occur if action isn’t taken early on. The first step is being aware of the problem and learning from the things happening around the world in countries like Japan, which are experiencing these shifts at a faster rate. The second step is understanding the differences between Japan and the other countries that may be at risk like the US, UK, China, South Korea, Italy, Spain, and many more (Alvarez 2023). As the graphs below demonstrate, Japanese workers push past the ‘normal retirement age’ more often than workers in other countries. While this is almost certainly related to the aforementioned economic pressure they feel to continue working, it’s also worth noting that there are differing perspectives on working late into one’s life in different cultures. Generally, working hard and for long hours is viewed positively in a familial context in Japan, but the same isn’t true for countries like America (Kopp 2024). This could mean that people in other countries won’t be as willing to work late into their lives, creating economic problems different or more severe than those in Japan.

References

Traphagan, J.W. and John Knight 2003. Demographic Change and the Family in Japan’s Aging Society. Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

Muhleisen, M. and Hamid Faruqee. 2001. “Japan: Population Aging and the Fiscal Challenge”. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 2024 (https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2001/03/muhleise.htm).

Iijima, S. and Yokoyama K. 2018. “Socioeconomic Factors and Policies Regarding Declining Birth Rates in Japan”. Retrieved 2024 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30270298/).

Loe, Meika. 2011. Aging Our Way. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Nargund, G. 2009. “Declining birth rate in developed countries: A radical policy re-think is required”. National Center for Biotechnology Information. Retrieved 2024 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4255510/).

Ueno, Chizuko. 1998. “The Declining Birthrate: Whose Problem?” Retrieved 2024 (https://www.ipss.go.jp/publication/e/R_s_p/No.7_P103.pdf).

Kopp, Rochelle. 2024. “Why Do Japanese Work Such Long Hours?” Japan Intercultural Counseling. Retrieved 2024 (https://japanintercultural.com/free-resources/articles/why-do-japanese-work-such-long-hours/#:~:text=Someone%20who%20works%20hard%20–%20and,their%20love%20by%20working%20hard.).

Narawad, Aniket. 2023. “Global Surveys Show People’s Growing Concern about Climate Change.” Journalism for the Energy Transition. Retrieved 2024 (https://www.cleanenergywire.org/factsheets/global-surveys-show-peoples-growing-concern-about-climate-change#:~:text=In%20the%20United%20Nations%20Development,survey%20asked%20respondents%20in%2050).

Wolf, Michael. 2024. “Japan Economic Outlook, January 2024.” Deloitte Insights. Retrieved 2024 (https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/economy/asia-pacific/japan-economic-outlook.html).

Martine, Julien and Jacques Jaussaud. 2018. “Prolonging Working Life in Japan: Issues and Practices Forelderly Employment in an Aging Society.” Contemporary Japan 30.

Moriyama, Tomohiko. 2022. “Why Does the Older Population in Japan Work So Much?” Japan Labor Issues 6(39).

Callen, Tim. 2024. “Gross Domestic Product: An Economy’s All.” Economic Concepts Explained. Retrieved 2024 (https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/fandd/issues/Series/Back-to-Basics/gross-domestic-product-GDP#:~:text=GDP%20measures%20the%20monetary%20value,the%20borders%20of%20a%20country.)

Katagiri, Keiko. 2023. “GOOD FOR HEALTH, BAD FOR SUBJECTIVE WELL-BEING: EFFECT OF CONTINUING WORK ON JAPANESE OLDER ADULTS.” Innovation of Aging 7(1):319-320.

Urata, Shujiro. 2024. “Combating Depopulation in Japan.” East Asia Forum. Retrieved 2024 (https://eastasiaforum.org/2024/03/05/combating-depopulation-in-japan/#:~:text=Japan’s%20population%20is%20rapidly%20aging,financial%20aid%20for%20young%20couples.).

Alvarez, Pablo. 2023. “Charted: The Rapid Decline of Global Birth Rates.” Visual Capitalist. Retrieved 2024 (https://www.visualcapitalist.com/cp/charted-rapid-decline-of-global-birth-rates/).

Images

“Growing old, gracefully: senior citizens in the workplace.” 2015. From The Japan Times. Retrieved 2024 (https://www.japantimes.co.jp/life/2015/12/19/lifestyle/growing-old-gracefully-senior-citizens-workplace/).

“Managing Japan’s Shrinking Labor Force With AI and Robots.” From International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 2024 (https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/fandd/issues/2018/06/japan-labor-force-artificial-intelligence-and-robots-schneider).

“OECD Historical Population Data and Projections.” OECD. Retrieved 2024.

“Annual Number of Births in Japan Falls Below 800,000 for First Time” 2019. From Nippon.com. Retrieved 2024 (https://www.nippon.com/en/japan-data/h00472/japanese-population-decline-accelerates-as-annual-births-dip-below-920-000-in-2018.html).

“How Japan keeps its elderly employed and active.” 2021. From dw.com. Retrieved 2024 (https://www.dw.com/en/how-japan-keeps-its-elderly-employed-and-active/a-59516633).