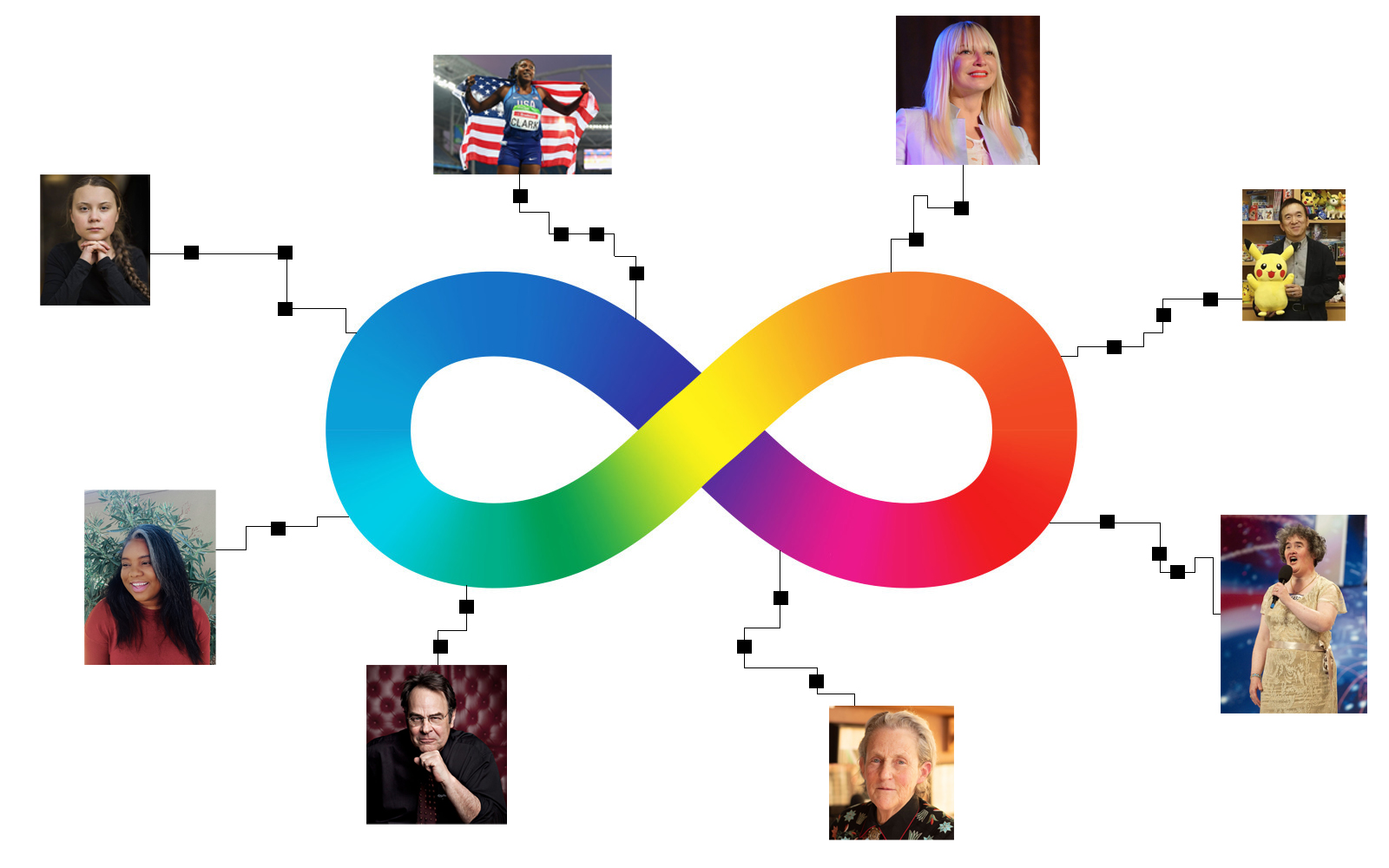

Barrier-breakers pictured around the Autism Acceptance logo (clockwise): Greta Thunberg, Breanna Clark, Sia, Satoshi Tajiri, Susan Boyle, Temple Grandin, Dan Aykroyd, Morgan Harper Nichols

“Start collecting a check. He’s a lifer.”

That’s what my parents were told by doctors when I was diagnosed on the autism spectrum. I would have no chance of going to public school, communicating effectively, doing things independently, or essentially becoming an independent person. Acting against this, my parents enrolled me in therapeutic and educational programs to help us understand who I was. Four years later, I was finally able to talk. Now my parents say I don’t shut up.

What would my life have been like if my parents had listened to that doctor’s advice? Are others less fortunate?

Autism’s Everywhere

Today, the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) defines autism spectrum order (ASD) as “a neurological and developmental disorder that affects how people interact with others, communicate, learn, and behave.” This definition is deliberately vague because autism presents itself in so many different ways, making it difficult to interpret case by case.

Because ASD is a spectrum, it can be characterized in numerous ways, including:

- Repetitive behaviors or intense interest in something over an extended period of time, which is also known as hyperfixating (Corden, Brewer, and Cage, 2021)

- Relying on nonverbal communication like physical pictures or sign language (NIMH)

- Struggling to understand others’ perspectives (NIMH)

- Sensory overload or insensitivity to touch, sound, and other stimuli (NIMH)

- Having difficulties communicating their emotions (NIMH)

Not all autistic people, however, exhibit all of these characteristics. Some might not have any of these, while others experience all of these and far more. Understanding this will help reduce universal thinking about varied cases of autism. With 1/36 children being diagnosed today (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), it’s a complicated topic that needs to be addressed.

Misconceptions as Barriers

Early ASD findings perpetuate misconceptions among the general public, like the thought that vaccines cause autism or that the disorder can be outgrown (Sanz-Cervera et al. 2017). These misconceptions relate to negative social stigmas, like both underestimating and overestimating intelligence along with generalizing social incapabilities (Aubé et al. 2020).

Credit: Vicky Kasala/The Image Bank/Getty Images

Misconceptions like these lead to autistic students experiencing the effects of implicit and explicit biases. One study suggests that autistic students are found to be less warm and incompetent by their typically developing peers, leading to avoidance and isolation (Aubé et al. 2020). Since social inclusion in elementary years is so formative (Reyes, Marquez, and Pacheco 2023), these challenges jumpstart societal setbacks for autistic children, like understanding social norms (Aubé et al. 2020).

Reducing Social Stigmas

Recent studies have shown that people’s negative perceptions of autism often come from not knowing a lot about it (Sanz-Cervera et al. 2017). One study presented non-autistic people with simulated realities of sensory overload, which proved effective through decreased measures of negative attitudes towards ASD (Tsujita et al. 2023).

ASD is also often interpreted as an illness rather than a natural way of being. This could result in autism being characterized as undesirable and as something to fight – or even as a family destroyer, as Autism Speaks once infamously characterized it (Robinson 2020 p. 226).

Tanager Place offers key strategies like not expecting eye contact and allowing routine for making autism a regular thing (Harvey 2021).

Autism Acceptance is a movement by autistic people, for autistic people that aims to move away from Autism Speaks and illness-based language in favor of normalization (“Acceptance, Not Just Awareness” 2023). For example, saying someone has autism has a disease-based connotation while saying someone is autistic builds the disorder as a regular part of their character. Framing autism as a regular genetic variation – as it is (Sanz-Cervera et al. 2017) – will help normalize it and reduce societal barriers.

Evidently, social misconceptions cause autistic people barriers to entry within society. Autistic people have long been unable to define themselves because non-autistic people and their listeners have done it for them. The efforts of perspective-based studies and Autism Acceptance are not all that it’s going to take. Yet, they are important steps in giving power back to autistic people while helping people understand autism as a different but normal way of interpreting the world.

References

“Acceptance, Not Just Awareness: Changing the Conversation around Autism.” 2023. UW Combined Fund Drive. Retrieved March 5, 2024 (https://hr.uw.edu/cfd/2023/03/27/changing-the-conversation/#:~:text=%E2%80%9CAwareness%20is%20knowing%20that%20somebody).

Aubé, Benoite, Alice Follenfant, Sébastien Godeau, and Cyrielle Derguy. 2021. “Public Stigma of Autism Spectrum Disorder at School: Implicit Attitudes Matter.” Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders 51(5). Retrieved February 18, 2024 (https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04635-9).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2023. “Data & Statistics on Autism Spectrum Disorder.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved February 18, 2024 (https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/data.html).

Corden, Kirsten, Rebecca Brewer, and Eilidh Cage. 2021. “A Systematic Review of Healthcare Professionals’ Knowledge, Self-Efficacy and Attitudes towards Working with Autistic People.” Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 9. Retrieved February 20, 2024 (https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-021-00263-w).

Cosner, Chelsea. 2023. “Love on the Spectrum: A Realistic TV Depiction of Autism Spectrum Disorder.” The American Journal of Psychiatry Residents’ Journal 19(1):22–22. Retrieved March 5, 2024 (https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp-rj.2023.190107).

Harvey, Brianna. 2021. “Autism Acceptance.” Tanager Place. Retrieved April 18, 2024 (https://tanagerplace.org/autism-acceptance/).

National Institute of Mental Health. 2023. “Autism Spectrum Disorder.” National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved February 20, 2024 (https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/autism-spectrum-disorders-asd).

Reyes Ortiz, Giovanni E., Félix Oscar Socorro Márquez and Rafael Gassón Pacheco A. 2023. “Theoretical Analysis of Social Inclusion and Social Leverage in the Anthropocene Era.” International Journal of Social Economics 50(4):478-490. Retrieved April 6, 2024 (https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSE-02-2022-0086).

Robinson, John. 2020. “My Time with Autism Speaks.” Pp. 221-232 in Autistic Community and the Neurodiversity Movement, edited by S. Kapp. Singapore Springer.

Sanz-Cervera, P., Fernández-Andrés, M.-I., Pastor-Cerezuela, G., & Tárraga-Mínguez, R. 2017. “Pre-Service Teachers’ Knowledge, Misconceptions and Gaps About Autism Spectrum Disorder.” Teacher Education and Special Education 40(3), 212-224. Retrieved April 6, 2024 (https://doi.org/10.1177/0888406417700963).

Tsujita, Masaki, Miho Homma, Shin-ichiro Kumagaya, and Yukie Nagai. 2023. “Comprehensive Intervention for Reducing Stigma of Autism Spectrum Disorders: Incorporating the Experience of Simulated Autistic Perception and Social Contact.” PLoS ONE 18(8). Retrieved February 18, 2024 (https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0288586).

Whiteley, Paul, et al. “Research, Clinical, and Sociological Aspects of Autism.” Frontiers in Psychiatry, vol. 12, 29 Apr. 2021, Retrieved April 5, 2024 (https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.481546).