The Employment Non-Discrimination Act (ENDA, 2013) was established to protect minorities in the workforce. Transgender employees, however, continue to report job loss due to their gender identity. Within the last five years, many trans people have described the many ways their employers have forced them out of employment while avoiding the consequences of the Employment Non-Discrimination Act (Sears et al. 2021). Despite protections existing for minority employees, discrimination in the workplace still financially cripples many trans people, often forcing them into homelessness.

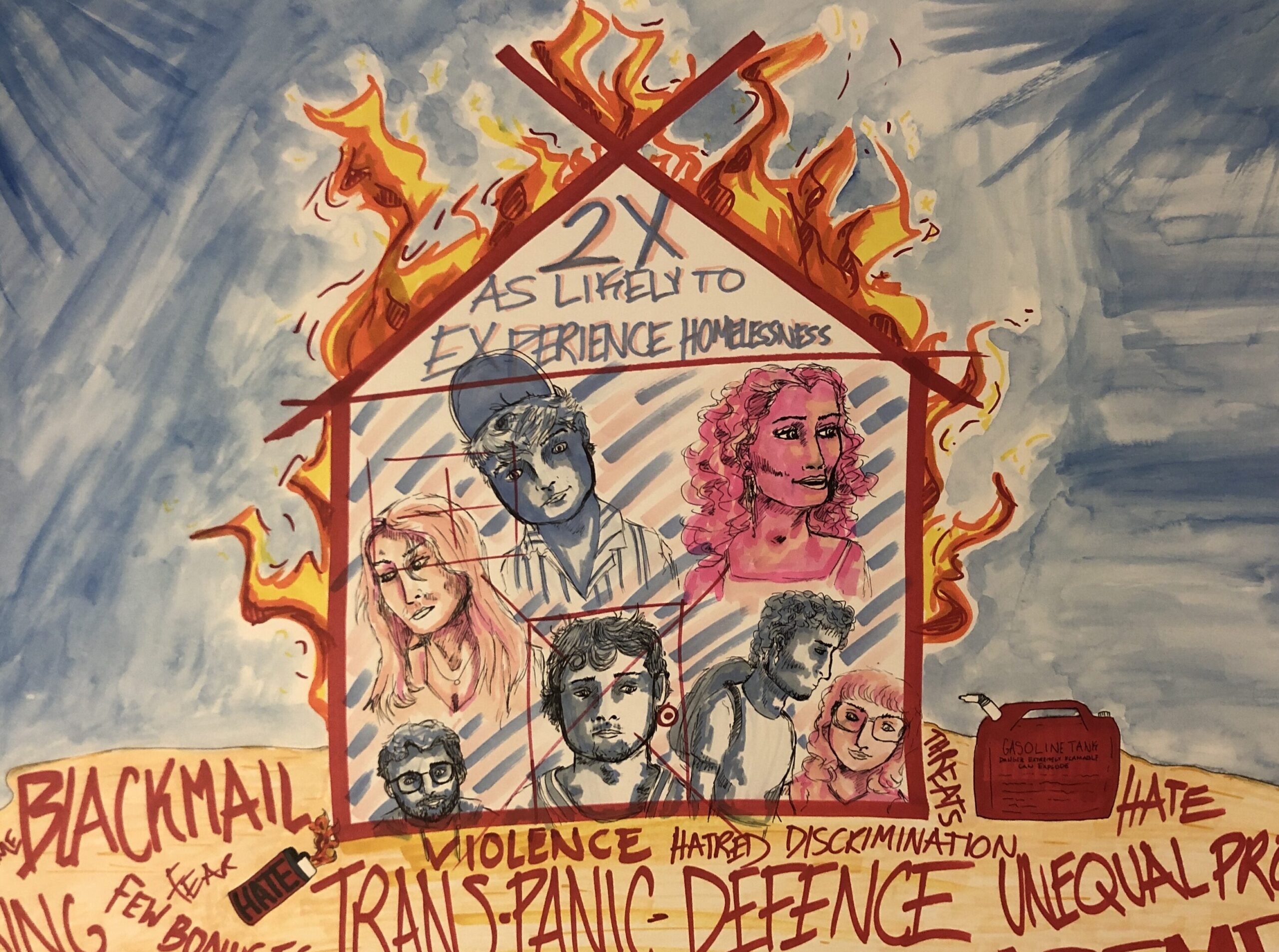

Transgender adults tend to struggle financially considerably more than the average American. In a 2011 report, transgender people were four times more likely to have a household income lower than $10,000 and were twice as likely to be unemployed (four times more likely for people of color). Transgender people also face homelessness at twice the rate of the general population (Grant et al. 2011). This financial inequality stems from employment inequality, where discrimination continues to persist despite protections.

The Questionable Effectiveness of the Employment Non-Discrimination Act

The root of trans people’s financial hardship often stems from workplace discrimination. As Kylar Broadus shared in his testimony to Congress in support of transgender people’s inclusion in the Employment Non-Discrimination Act, after coming out as trans and beginning his transition, he was “constructively discharged” from his job. He described that, even 15 years after he was fired from his job, he still struggled to recover financially (Senate Health, Education, Labor 2012).

Despite the passing of the ENDA, transgender people continue to report employer discrimination. Employers still discriminate and harass employees, often finding ways around directly firing employees. Reports include employers blackmailing employees into leaving, or limiting their hours until the employee quits themselves (Sears et al. 2021). Many of these reports occurred within the last five years, following the increase in anti-discrimination protections (Sears et al. 2021). Despite anti-discrimination laws to protect minority groups, transgender people reported high rates of being fired due to their gender identity at 26% (Grant et al. 2011). This demonstrates that even with workplace protections, discrimination still exists.

“Because I’m gay and trans I got fired and blackmailed to leave.”

Sears et al. 2021

– A Black transgender gay man from New Jersey

Employer discrimination cases are notoriously hard to win. If an employer has fired a transgender employee for an alternative reason and the employee lacks physical evidence, it can be very difficult to prove (Selmis 2001). It becomes very difficult to determine the employers’ intent if it is not written or documented. Loss of a job leads to lost income, and furthermore, lower financial power to obtain a legal defense.

Consequences For Transgender People

As a result of discrimination-induced financial hardship, many transgender people resort to the underground economy doing sex work or selling drugs. Sex work also may be a cause contributing to the high rate of HIV in the homeless transgender population (Grant et al. 2011). 10–50% of homeless individuals engage in survival sex at some point and this is often done to access housing. Many reported that while seeking shelter at homeless shelters, they were either denied due to their identity, or faced discrimination, harassment, and assault. 44% reported leaving shelters on their own because of threats to their personal safety (Kattari et al. 2017, Grant 2011). Survival sex is often a way for homeless transgender people to access food and housing when they can’t access shelters and other organizations.

Due to involvement in the underground economy, which usually involves criminalized sales, unemployed transgender people are 85% more likely to be imprisoned and more likely to be victims of murder (Grant et al. 2011). Circumstances force economically disadvantaged transgender people to resort to illegal activity to survive, and as a result, many transgender people are imprisoned or killed. Transgender people that end up in prison also leave prison with criminal records, which can make it even harder for them to find a job after release.

Vulnerable Populations

Certain groups within the transgender community are more prone to facing discrimination. Individuals that struggle to “pass” (be socially identified as their gender) or exist outside of the binary gender roles, often face higher rates of discrimination. Individuals who “pass” are statistically safer from discrimination and victimization, as they aren’t perceived to be transgender (Flynn 2021).

Additionally, trans people that are also part of other minority groups tend to increase discrimination rates. Transgender women of color tend to experience the highest rates of discrimination and harassment (Forestiere 2020). Among transgender women of color, discrimination in the form of transphobia, homophobia, and racism often coincide. Trans women are more likely to be hurt by men who view being attracted to a trans woman (specifically someone born with male biology) as a threat to their masculinity or heterosexuality. The murders of transgender women are often falsely justified by arguments of deception and sexual assault after a man discovers that a woman he pursues is transgender (Andresen 2022). This, on top of the intersectionality of racism, leads to transgender women of color having the highest rates of discrimination and homelessness, and making up the majority of transgender murder victims.

Conclusions

The transgender adult population disproportionately experiences homelessness and many other hardships as a product of discrimination based on their gender identity, and this needs to be acknowledged in professional settings. Non-discrimination laws exist so transgender individuals can have a stable, livable income and a place to live, but unfortunately, this is still not the case for many transgender people.

References

Carsten, Andresen. 2022. “Comparing the Gay and Trans Panic Defenses, Women & Criminal Justice,” 32:1-2, 219-241, DOI: 10.1080/08974454.2021.1965067

Flynn S, Smith NG. 2021. “Interactions between blending and identity concealment: Effects on non-binary people’s distress and experiences of victimization.” PLoS ONE 16(3): e0248970. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0248970

Forestiere, Annamarie. 2020. “America’s War on Black Trans Women.” Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review, um=rss&utm_campaign=americas-war-on-black-trans-women.

Grant Jaime, Mottet Lisa, Tanis Justin. 2011. “Injustice at Every Turn: A Report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey.” https://transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/resources/NTDS_Report.pdf.

Kattari, S. K., & Begun, S. 2017. “On the Margins of Marginalized: Transgender Homelessness and Survival Sex. Affilia,” 32(1), 92–103. https://doi-org.ez.hamilton.edu/10.1177/0886109916651904

Sears Brad, Mallory Christy, Flores Andrew, Conron Kerith. 2021. “LGBT People’s Experiences of Workplace Discrimination and Harassment” UCLA Williams Institute, https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/Workplace-Discrimination-Sep-2021.pdf

Selmi Michael. 2001.“Why are Employment Discrimination Cases So Hard to Win?” 61 Louisiana Law Review. Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev/vol61/iss3/4

Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee Hearing: “Equality At Work: The Employment Non-Discrimination Act,” focusing on employment discrimination against lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender Americans and the “Employment Non-Discrimination Act.”[1]. (2012). In Congressional Documents and Publications. Federal Information & News Dispatch, LLC.

“S.815 – 113th Congress (2013-2014): Employment Non-Discrimination Act of 2013.” Congress.gov, Library of Congress, 8 January 2014, https://www.congress.gov/bill/113th-congress/senate-bill/815.