Black children are disproportionately subject to school discipline in the United States (Crenshaw 2015; Entwisle 2007; Farkas 1990; Onyeka-Crawford 2017; Owens 2016; Skiba 2014). Although the disproportionate discipline of Black boys has generated much scholarship (Losen 2010; Raffaele Mendez 2003; Owens 2016), less attention has been paid to the disproportionate discipline of Black girls (Crenshaw 2015:26). Disciplinary responses are informed by stereotypes (Morris, M 2012:4), and analyzing anti-black and patriarchal stereotypes positions Black girls at the brunt of school discipline (Crenshaw 2015:46).

Anti-Black and Patriarchal Patterns of Discipline

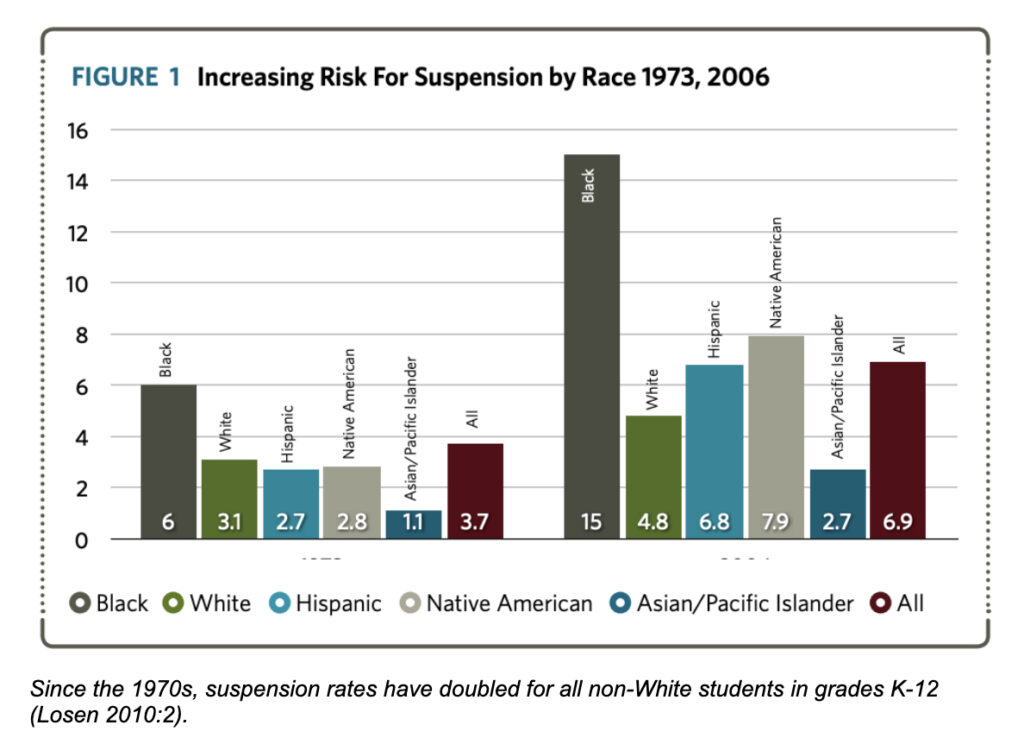

Black children face some sort of school discipline, such as suspension, more often than children of other races (Losen 2010:2; Raffaele Mendez 2003:30). Black students are more than three times as likely to be suspended than their white counterparts. From 1973 to 2006 the suspension rate gap between white and Black students grew by ten percentage points (Losen 2010:3).

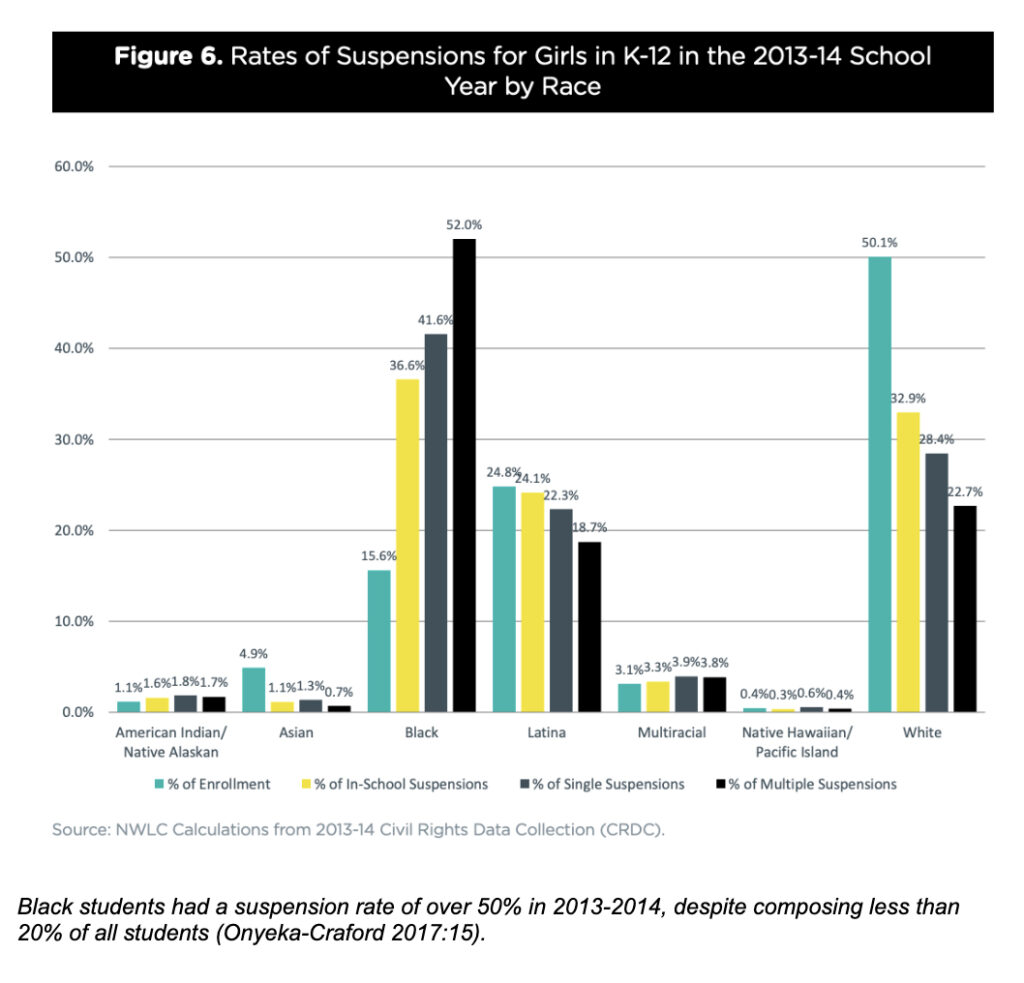

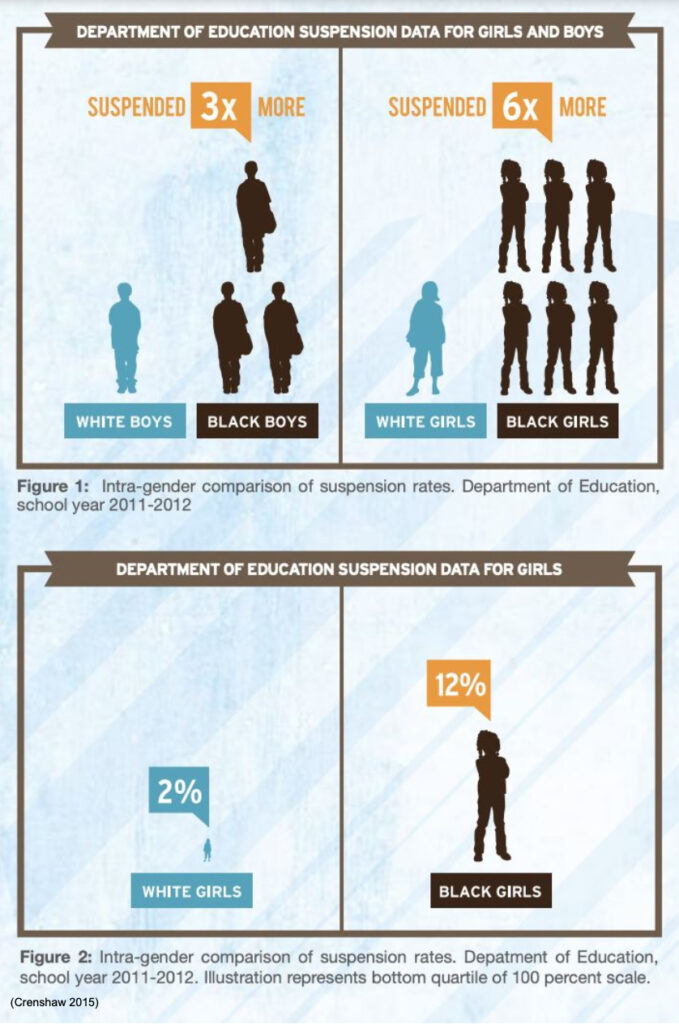

While Black boys face discipline most often, in relation to girls of other races, Black girls are more commonly disciplined (Crenshaw 2015, Morris 2017; Onyeka-Crawford 2017). Black boys are twice as likely to face disciplinary responses compared to their white counterparts, while Black girls are three times as likely (Morris 2017:143). Therefore Black girls have a higher relative risk for suspension compared to white girls than Black boys as compared to white boys. The high rates of discipline Black girls face from educators raises questions about how both gender and race contribute to such disparate outcomes (Crenshaw 2015:19).

Educators’ Stereotypes Shaping Discipline

Educators’ implicit biases and stereotypes inform the disciplinary response they mete out to Black boys and Black girls (Morris, M 2012:4). Discipline disparities are due to educators’ implicit bias in decisions to refer a student for disciplinary action and administrators’ subsequent decisions to carry out referrals (Amos 2021).

“Teacher reports of discipline issues […] arise from a cycle of negative interactions that are influenced by negative social stereotypes between teachers and students.”

(De witte 2019)

Studies suggest that behavioral difficulties with self regulation, attention span, and social competence cause Black boys to face more discipline (Owens 2016:237). However, considering race and gender suggests that the aforementioned “behavioral difficulties” reflect educators’ stereotypes of Black boys. Although stereotypes about Black boys and the disproportionate discipline they face is well researched, less research investigates discriminatory disciplining of Black girls (George 2015; Morris, M 2017).

Stereotypes of Black girls are rooted in the United States’ history of slavery, and have long been used to justify the sexual abuse and exploitation of African American women (George 2015:107). White stereotypes of African American women as sexually available and promiscuous and of white women as sexually pure and moral places African American women below white women in a white patriarchal hierarchy (George 2015). Today educators’ unconscious stereotypes of Black girls as loud, confrontational, disruptive, and aggressive (George 2015:101) reinforces this racial and patriarchal hierarchy. Punishing Black girls for violating white feminine ideals augments educators’ disproportionate discipline of African American girls (George 2015:108-109; Onyeka Crawford 2017:3).

Beyond The Classroom

When researching who disciplinary systems impact, studies often fail to consider the historical, institutional, and social implications that Black girls face (Crenshaw 2015:16). Failing to acknowledge how Black girls are uniquely impacted by school discipline fuels the school-to-prison pipeline (George 2015:104). The school-to-prison pipeline refers to the school practices (conditions and consciousness) that criminalize students of color in the United States, and how this criminalization leads to the incarceration of youth (Morris M.2012:2). African American girls are the fastest-growing segment of the juvenile justice system (Crenshaw 2015:8; George 2015:104). Facing suspensions or other forms of school discipline affects Black girls’ time in the classroom, heightens drop-out rates, increases their interactions with the juvenile justice system, and fosters long term economic consequences (Crenshaw 2015:27; George 2015:105). Individual instances of misbehavior cannot be at the root of school discipline when Black students are disproportionately targeted by educators’ stereotypes.

Sources

Amos, Lauren. 2021. “Eliminating School Discipline Disparities: What We Know and Don’t Know About the Effectiveness of Alternatives to Suspension and Expulsion.” Mathematica, Retrieved April 11, 2023. (https://www.mathematica.org/blogs/eliminating-school-discipline-disparities-what-we-know-and-dont-know-about-the-effectiveness#:~:text=Discipline%20disparities%20are%20driven%20by,in%20response%20to%20those%20referrals.)

Camera, Lauren. 2016. “Boys Bear the Brunt of School Discipline.” U.S. News, Retrieved February 26, 2023. (https://www.usnews.com/news/articles/2016-06-22/boys-bear-the-brunt-of-school-discipline)

Camera, Lauren. 2017. “Black Girls Are Twice as Likely to Be Suspended, In Every State.” U.S. News, Retrieved February 26, 2023. (https://www.usnews.com/news/education-news/articles/2017-05-09/black-girls-are-twice-as-likely-to-be-suspended-in-every-state)

Crenshaw, Kimberlé W., Ocen, Priscilla, and Jyoti Nanda. 2015. “Black Girls Matter: Pushed Out, Overpoliced, and Underprotected.” African American Policy Forum 1-49. Retrieved February 27, 2023 (https://44bbdc6e-01a4-4a9a-88bc-731c6524888e.filesusr.com/ugd/b77e03_e92d6e80f7034f30bf843ea7068f52d6.pdf)

De Witte, Melissa. 2019. “Stanford scholars develop interventions to reduce disparities in school discipline and support belonging among negatively stereotyped boys.” Stanford University News, Retrieved April 09, 2023 (https://news.stanford.edu/2019/04/03/reduce-racial-disparities-school-discipline/).

Entwisle, Doris R., Karl L. Alexander, and Linda S. Olson. 2007. “Early Schooling: The Handicap of Being Poor and Male.” Sociology and Education 80(2):114-138. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20452700

Farkas, George, Robert P. Grobe, Daniel Sheehan, and Yuan Shuan. 1990. “Cultural Resources and School Success: Gender, Ethnicity, and Poverty Groups within an Urban School District.” American Sociological Review 55(1):127-42. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/2095708.pdf

George, Janel A. 2015. “Stereotype and School Pushout: Race, Gender, and Discipline Disparities.” University of Arkansas Law Review. 68(101):102-129. https://law.uark.edu/alr/PDFs/68-1/alr-68-1-101-129George.pdf

Green, Erica L., Mark Walker, and Eliza Shapiro. 2020. “‘A Battle for the Souls of Black Girls.” The New York Times, Retrieved April 09, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/01/us/politics/black-girls-school-discipline.html?auth=login-google1tap&login=google1tap

Losen, Daniel J., and Russell J. Skiba. 2010. Suspended Education: Urban Middle Schools in Crisis. Montgomery, Alabama: Southern Poverty Law Center. Accessed February 17, 2023. https://civilrightsproject.ucla.edu/research/k-12-education/school-discipline/suspended-education-urban-middle-schools-in-crisis/Suspended-Education_FINAL-2.pdf

Morris, Edward W., and Brea L. Perry. 2017. “Girls Behaving Badly? Race, Gender, and Subjective Evaluation in the Discipline of African American Girls.” American Sociological Association 90(2):127-48. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0038040717694876

Morris, Monique W. 2012. Race, Gender and the School-to-prison Pipeline. New York, NY: African American Policy Forum. https://schottfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/Morris-Race-Gender-and-the-School-to-Prison-Pipeline.pdf

Onyeka-Crawford, Adaku., Kayla Patrick, and Neena Chaudhry. 2017. “Let Her Learn: Stopping School Pushout for Girls of Color.” National Women’s Law Center. Retrieved February 26, 2023. https://nwlc.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/final_nwlc_Gates_GirlsofColor.pdf

Owens, Jayanti. 2016. “Early Childhood Behavior Problems and the Gender Gap in Educational Attainment in the United States.” American Sociological Association 89(3):236-258. https://watson.brown.edu/files/watson/imce/news/explore/2016/SOE_July_2016_Jayanti_Owens_Study.pdf

Prudence, Carter L., Russell Skiba, Mariella I. Arredondo, and Mica Pollock. 2017. “You Can’t Fix What You Don’t Look At: Acknowledging Race in Addressing Racial Discipline Disparities.” Sage Publication: Urban Education 52(2):207-35. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0042085916660350

Raffaele Mendez, Linda M., and Howard M. Knoff. 2003. “Who Gets Suspended from School and Why: A Demographic Analysis of Schools and Disciplinary Infractions in a Large School District.” Education and Treatment of Children 26(1):30-51. https://www.jstor.org/stable/42900535?seq=1

Skiba, Russell J., Choong-Geun Chung, Megan Trachok, Timberly L. Baker, Adam Sheya, and Robin L. Hughes. 2014. “Parsing Disciplinary Disproportionality Contributions of Infraction, Student, and School Characteristics to Out-of-school Suspension and Expulsion.” American Educational Research Journal 51(4):640-670. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.3102/0002831214541670