Doctors are often seen as heroes. They ensure our children are healthy, treat and cure adult ailments, and then provide the elderly necessary care to thrive in their golden years. Should they also help us to die when we are ready?

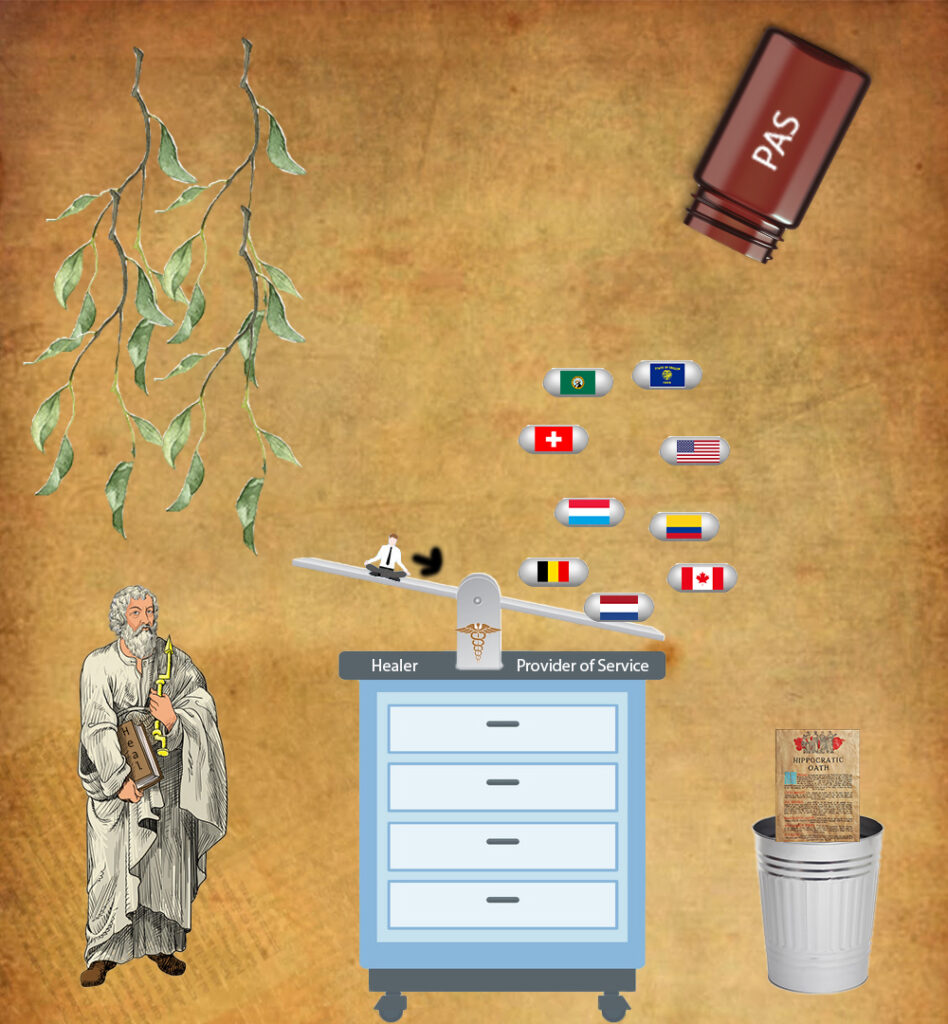

Physician assisted suicide (PAS) is the controversial process through which a doctor provides a patient with the resources and instructions to end their own life (American Medical Association). This fairly novel solution for the terminally ill and unhappy raises several questions. What is the role of the doctor and how does PAS change their role? Is patient autonomy important enough to considerably reshape the role of the physician, and if so, how might this affect the future of healthcare?

Physician Views of PAS: Healer vs. Provider of Service

There has been limited research on physician attitudes to the legalization of PAS. However, the extant research suggests:

- Only 15.6% of Hawaiian physicians are willing to participate in PAS (Siaw and Tan 1996)

- 74% of Washington state physicians opposed to PAS believe it is outside role of physician (Cohen et al. 1994)

- Approval of PAS has an inverse relationship to clinical experience (Rivera et al. 2000)

- Physicians in palliative care, hematology, and oncology (those with more experience helping terminally ill patients) are less likely to support PAS (Lavery et al. 1997)

Why do the statistics show a physician aversion to PAS? A doctor’s job description has always included three things: to save, extend, and improve lives (ILS Hospitals). PAS shifts the fundamental role of doctor by making death a treatment option. Accepting death as a form of treatment clashes with the core values of a physician and transforms them from a healer into a “provider of service” (Yang and Curlin 2016). The chart below (Beohnlein 1999) examines the main differences between a healer and a provider of service.

| Physician as a Healer | Physician as a Provider of Service |

| – Medical expertise should be used only to treat illness and preserve/improve life – Patients should trust that the doctor is only trying to cure disease and improve quality of life – In end of life situations, physicians should never abandon a patient, respect patient autonomy (refusing treatment), communicate with and support patients, and provide pain control and comfort care when needed | – Medical expertise should satisfy desires of patient or of the law – Patients should have complete autonomy – In end of life situations, death as a treatment should be a possibility |

Those in favor of physician assisted suicide suggest it is a compassionate act, helping a dying, suffering patient reach their eventual end just a little bit sooner to preserve their dignity and eliminate their pain. For example, a study of Dutch patients considering PAS found that they sought to have a dignified end of life and to stop suffering (Pronk et al. 2022). Supporters of PAS would say that this rationale is in line with having the right to die and possessing full self determination (Lavery et al. 1997).

However, there are costs of legalizing PAS that also must be examined. The dream of full self determination is often not a reality: money, family members, and societal pressures can have an influence (Boehnlein 1999). Additionally, consider the previously mentioned statistic that described how those with more clinical experience in end of life scenarios are significantly less likely to support PAS. This could be because these physicians see first-hand the influence its legalization could have on patients. An Oregon physician, James Boehnlein, specifically described potential negative effects of PAS based on his time in the profession (Boehnlein 1999). These include causing a patient to potentially:

- Feel as if living with an illness is their fault

- Feel like a burden to their family and to the larger medical system

- Have a strained relationship with their physician, knowing that he/she is not only concerned with improving and preserving life

Dr. Boehnlein worries the definition of debility can expand depending on who is interpreting the specific situation, fearing that the terminally ill can expand to the moderately ill, which can further expand to the “unfit”, a vague description largely shaped by the eye of the beholder (Boehnlein 1999).

PAS in Practice

In 2001, the Netherlands was the first country to formally legalize PAS (Alliance Vita). Since then, ten U.S. states, the District of Columbia and several other countries have joined them in legalizing physician assisted suicide. In the Netherlands, infringements on the initial law have increased and its interpretation has loosened since its initial legalization (Alliance Vita). For instance, Dutch law now considers mental illness to be acceptable grounds for application of PAS (Alliance Vita). Parliament recently attempted to pass a bill legalizing PAS for those over 70 that are “tired of life” (Alliance Vita). Additionally, the Dutch ethics and law commission has initiated discussions about allowing euthanasia for mentally ill children under the age of 12 (Alliance Vita).

Frighteningly, some patients in the Netherlands have requested PAS because of the poor palliative care they were receiving (Alliance Vita). This could be caused by the health system viewing elderly lives as a burden and could be evidence of the Dutch health care system beginning to fall down the slippery slope that PAS introduces.

Implementation of PAS by physicians has morally strained Dutch doctors in ways they don’t feel outsiders can comprehend. 60% of physicians have felt pressured by the patient or family into executing PAS when they believed it was not the right situation to make that solution acceptable (Alliance Vita). Additionally, 90% of physicians felt that lawmakers and citizens did not understand the burden they felt having to make these irreversible decisions about patients’ lives (Alliance Vita).

Concluding Thoughts

Physician assisted suicide can be used to solve personal troubles. In very specific cases, it may be the right decision for a patient. However, the implications of its legalization have the potential to cause much larger societal issues. These include physician role confusion, the breakdown of funding for palliative care, viewing a life as not worth saving, and forcing the burden of an illness onto a patient instead of seeing that patient as a victim (Boehnlein 1999). I personally believe that the adverse effects PAS has on society seem to outweigh the personal autonomy gained in a few, isolated cases. Maintaining the historical role of healer is crucial for preserving the balance between what is best for the patient and what is best for society.

References

- American Medical Association. “Physician-Assisted Suicide”. Retrieved October 16th, 2022

- Boehnlein, James K. 1999. “The Case Against Assisted Suicide.” Community Mental Health Journal

- Cohen, J.S. et al. 1994. Attitudes toward Assisted Suicide and Euthanasia among Physicians in Washington State. The New England Journal of Medicine. 331:89-94

- Euthanasia in the Netherlands. 2017. Alliance Vita.

- Lavery, James V., B.M. Dickens, J.M. Boyle, P.A. Singer. 1997. Euthanasia and assisted suicide. Can Med Assoc J 156:1405-8

- Pronk, R., Willems, D.L. & van de Vathorst, S. 2022. Feeling Seen, Being Heard: Perspectives of Patients Suffering from Mental Illness on the Possibility of Physician-Assisted Death in the Netherlands. Cult Med Psychiatry 46:475–489.

- Ramirez Rivera, J., Rodríguez, R., & Otero Igaravidez, Y. 2000. Attitudes toward euthanasia, assisted suicide and termination of life-sustaining treatment of Puerto Rican medical students, medical residents, and faculty. Boletin de la Asociacion Medica de Puerto Rico 92(1-3):18–21.

- Siaw, L. K., and S. Y. Tan 1996. How Hawaii’s doctors feel about physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia: an overview. Hawaii medical journal 55(12):296–298.

- Yang, Tony Y., Farr A. Curlin. 2016. “Why Physicians Should Oppose Assisted Suicide.” JAMA. (3):247-248

- 2017. “Importance and Role of a Doctor in the Society.” ILS Hospitals. Retrieved October 16th, 2022