Thuy Pham

The 1970s was a period of turmoil in Southeast Asia, with civil wars occurring in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia. After the Cambodian Civil War (1967-1975), fought between the Communist Party of Kampuchea and the government forces of the Kingdom of Cambodia, ended with the establishment of the Khmer Rouge(1975-1979), families were separated and millions died of disease, starvation, or execution. Similarly, the Laotian Civil War (1959-1975) was between the Communist Pathet Lao and the Royal Lao Government, while North and South Vietnam struggled for unification during the Vietnam Civil War (1955-1975). By 1975, civil wars in Laos and Vietnam ended with the Pathet Lao seizing control and North Vietnam gaining victory. As a result of these political changes, thousands of Cambodians, Laotians, and tribal groups (Hmong and Mien) took refuge in foreign countries. The Vietnamese immigrated in 2 waves: while the first wave in 1975 was composed mainly of educated and professional classes, the second wave refugees, also known as the “boat people”, were mostly from rural and less educated backgrounds (Hsu 2003: 196).

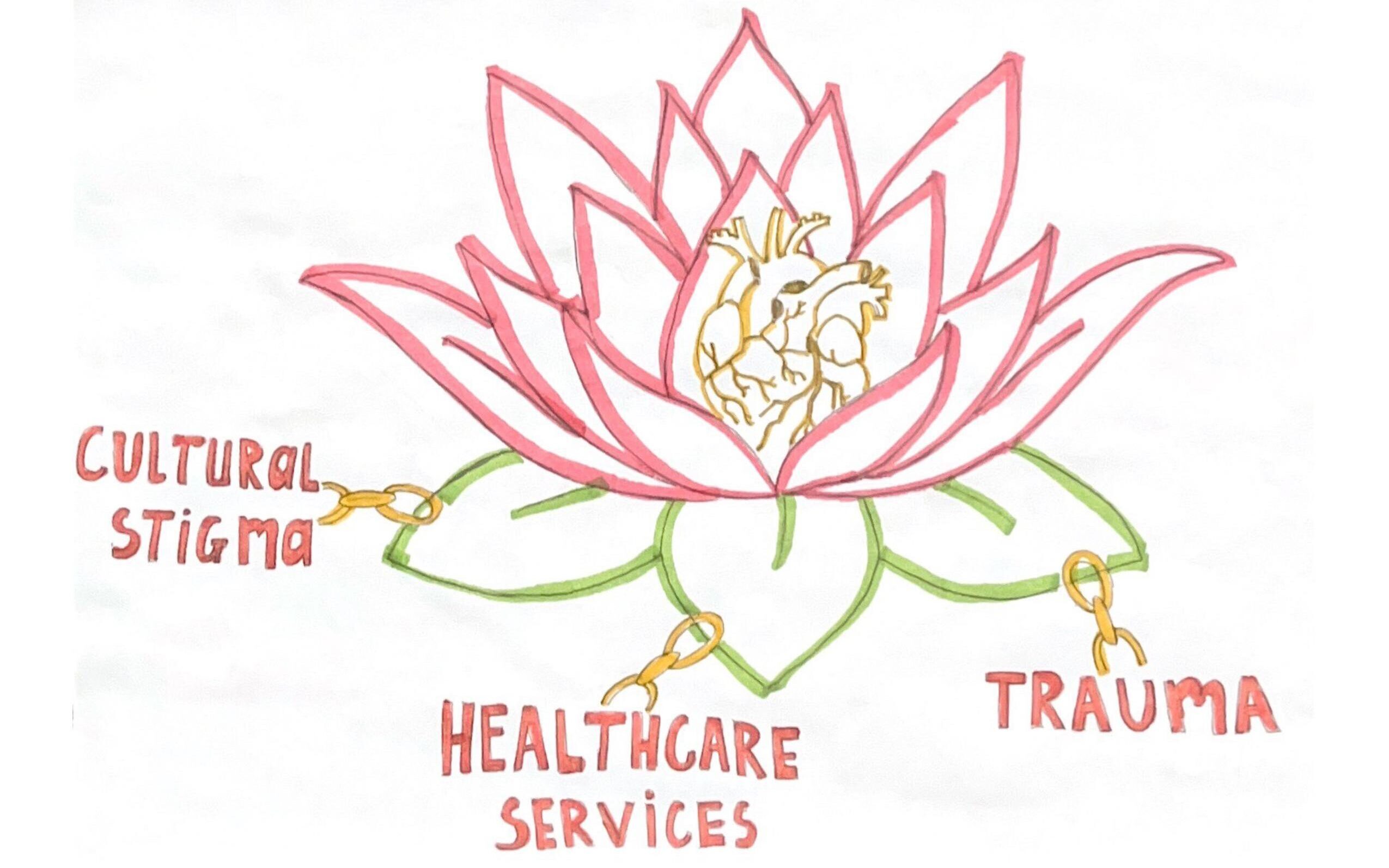

Many of the SEA refugees were resettled to poor urban cities with limited resources and greater social problems already in place (Kim 2018: 390). As they navigate their American dreams, SEA refugees continue to face considerable mental health challenges from pre-migration trauma and post-migration factors such as struggles in adapting, limited resources (Kim 2018: 386), as well as barriers from the healthcare system and the ethnic stigma of seeking mental health services within their own communities.

Susceptibility to Poor Mental Health

War Trauma

Surviving refugees’ physical and mental health carries the negative consequences of the torture and traumatic experiences that occurred during wartime and/or the migration process (Hoffman 2020: 1232). The body’s stress response to traumatic memories results in an abnormal level of cortisol, increasing the likelihood of developing diseases such as hypertension, heart disease, depression, and anxiety (Wall 2008: 107). As of 2003, anxiety, PTSD, and depression were among the most diagnosed mental health problems among SEA refugee patients (Hsu 2003: 200).

Although most of the refugees were of older ages during the time of migration, for children who survived the war, traumatic experiences and their symptoms continued to interfere with their subsequent development and into the beginning of their adult lives (Hsu 2003: 204). This cycle of trauma also continues onto future generations who were not originally exposed through a process called the inter-generational transmission of trauma (Hoffman 2020: 1232).

Language Challenges

SEA refugees from low socioeconomic backgrounds with limited English proficiency (LEP) are likely to be identified as a group at high risk of both poor physical and mental health (Kim 2011: 1250). In recent studies based in California, older immigrants with LEP are less likely to have good self-reported health and emotional health than those with English proficiency (Kim 2011: 1246). Due to their older age during the time of immigration, many refugees struggle to adapt and adjust (Kim 2018: 390). Not surprisingly, those with LEP tend to have a harder time communicating their symptoms to their healthcare provider and understanding the doctor’s prescription. The inefficient communication can sometimes result in the inability to understand their medical situation and inadequate care (Kim 2011: 1247).

Cultural and Public Stigma within SEA communities

Due to the forced nature of emigration, SEA refugees tend to show high attachment to their native culture while compromising acceptance of Western ideals, including medical practices (Ying 2007:62). Unlike Western medicalized approaches to mental health treatment, each of these SEA cultures has its own protocols and belief system for both the causation and treatment of mental issues. Rather than biological explanations, SEA refugees in the U.S. are more inclined to associate mental health problems with an individual’s habits and surroundings, and sometimes supernatural causes (Fung 2007: 62). In a 2019 study conducted in New Orleans, older generations of SEA thought “craziness” and “madness” are due to family and economic problems and reported that these issues will eventually be solved with emotional and financial support (Do 2020: 843). Others might apply a Buddhist worldview, which is common in SEA, viewing mental health problems as punishment that accumulated from the bad karma of a previous life. Moreover, a person with poor mental health symptoms can be also interpreted by others in the same community as being punished for the sins of their ancestors, thus disgracing their family (Do 2020: 840).

Stigma, defined by sociologist Erving Goffman, is a process by which an individual internalizes stigmatizing characteristics and develops fears and anxiety about being treated differently from others. In a culture that values collectivism, placing communal needs above an individual’s needs and doing things that benefit a community rather than yourself is the norm (Shea and Yeh, 2008: 157-172). When one rejects, rather than deals with their mental illness, they are “saving the family’s face,” and protecting the familial reputation. In addition to the burden of being labeled as having a “broken mind” and “crazy”, SEAs who accept the mental illness diagnoses are also likely to suffer from social exclusion, shame, and embarrassment from their community (Do 2020: 844).

Emerging Healing Practices

Advocated by the Harvard Program in Refugee Trauma, storytelling is essential in healing traumatic memories when shared in a manner that is beneficial to both the survivor and the listener. To tell a story effectively, survivors must face expressing their emotions in the balance between humiliation, sadness, and despair vs fear, anger, and the need for revenge. By shifting the focus from strong emotions, survivors can share their stories using metaphor and reasoning. An empathetic audience facilitates successful storytelling from the survivor because they accept the images, themes, and symbols of the storyteller. When we listen with empathy, we “enter into the other’s world with compassion”. However, some emotional memories fail to be resolved because of the survivors’ desire to keep those memories alive to keep their loved ones close (Wall 2008: 108-109).

Bridging Cultural Differences

With many SEA refugees seeking out professional mental health providers at the request of their general practitioner, it is essential for providers to educate them about Western mental health services. Instead of rejecting their cultural approach to the illness, providers can also consider promoting traditional healing methods as complementary to the western medicalized approach (Hsu 2003: 207).

Furthermore, Increased use of interpreters can prevent miscommunication and misdiagnosis among SEA refugees. The interpreter should undergo thorough multicultural training in an effort to reduce potential interpreter biases. Physicians should also use reliable and conceptually valid assessment tools for SEA refugee patients. As of 2003, Hopkins Symptom Checklist and Harvard Trauma Questionnaire are some of the few culturally validated assessment tools (Hsu 2003: 206).

References

Do, Mai, Jennifer McCleary, and Diem Nguyen. 2020. “Mental Illness Public Stigma and Generational Differences Among Vietnamese Americans” Community Mental Health Journal, 56, 839-853

Fung, Kenneth, Yuk-Lin Renita Wong. 2007. “ Factors Influencing Attitudes Towards Seeking Professional Help Among East and Southeast Asian Immigrant and Refugee Women.” Sage Publications 53 (3), 216-231

Hsu, Eugenia, Corrie A. Davies, and David J. Hansen. 2003. “Understanding mental health needs of Southeast Asian refugees: Historical, cultural, and contextual challenges” Clinical Psychological Review, 24, 193-213

Kim, Isok, Mary Keovisal, and Woosok Kim. 2018. “Trauma, Discrimination, and Psychological Distress Across Vietnamese Refugees and Immigrants: A Life Course Perspective” Community Mental Health Journal 55, 385-393

Kim, G., Worley,C. B., Allen, R.S., Vinson, L., Crowther, M.R., Parmelee, P., and Chiriboga, D.A. 2011. “Vulnerability of older Latino and Asian Immigrants with limited English Proficiency.” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 59(7), 1246-1252

Shea, M., Yeh,C. J..2008. “Asian American students’ cultural values, stigma, and relational self-construal: Correlates and attitudes toward professional help-seeking.” Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 30(2), 157-172

Wall, Robert Brian. 2008. “Healing from War and Trauma: Southeast Asians in the U.S.- A Buddhist Perspective and the Harvard Program in Refugee Trauma.” Human Architecture: Journal of the Sociology of Self-Knowledge, 3, 105-111.

Ying, Yu-wen, Meekyung Han. .2007. “The Longitudinal Effect of Intergenerational Gap in Acculturation on Conflict and Mental Health in Southeast Asian American Adolescents.” American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 77 (1), 61-66

Hoffman, Sarah, Maria M. Vukovich, and Abigail H. Gewirtz. 2020. “Mechanisms Explaining the Relationship Between Maternal Torture Exposure and Youth Adjustment in Resettled Refugees: A Pilot Examination of Generational Trauma Through Moderated Mediation.” Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 22, 1232-1239