It is a gusty rainy night on the streets of central Manhattan. Heat and steam rises up from the sewers. Subways howl with thousands of people traveling underground. Cuddled up in a corner, Ethan is soaked to the bone trying to catch a few winks of sleep without freezing to death. He sees the corner of Bryant Park Station as an alternative to the harsh conditions inside the shelters. He’s tired of being robbed and getting kicked by random people’s feet when he tries to sleep in shelters. Instead he faces the biting cold, constant harassment, and unending sense of being ignored by the entire world.

I met Ethan during fall break in New York. After COVID-19, he went from having stable housing to being homeless. Ethan’s mother lost her job as a cashier during the pandemic and sold everything in the house. Without a job and running out of money, he moved out of a home he shared with four other people, hoping to move to a warmer place sleeping outside.

It Isn’t Just About Him

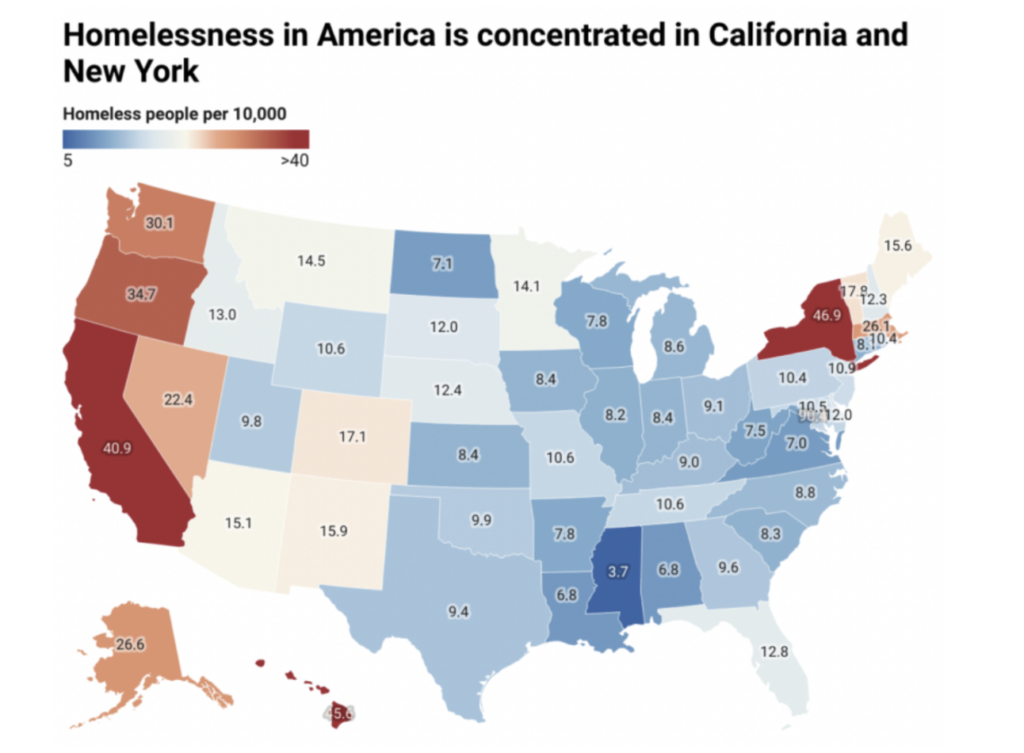

This story isn’t just about Ethan. Countless stories like this happen every day across the country. Rising homelessness results in part by the roaring prices in big cities such as New York and San Francisco, two of the cities with the largest homeless populations in America. A five percent increase in housing rent led to an additional 2,982 people living on the street by 2018 (McPherson and Marian 2018). This compounds the pre-existing high homelessness populations in these cities before COVID.

Map: Jeremy Ney@AmericanInequality Source: HUD Created with Datawrapper

An Insufficient Safety Net for the Homelessness

Growing homelessness is a failure of the American welfare system. President Bill Clinton established Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF) as a welfare reform bill in 1996 to offer limited cash assistance for the unemployed families.

Many families have lost aid with the shift to TANF because of strict policies that require a job offer before applying for assistance (Hovmand 2019). Therefore, people who receive aid from the safety net have shifted dramatically, with the majority of assistance dollars now going to those who are working (Scholz et al. 2009). A substantial number of poor families have fallen through the cracks, disconnected from both stable, adequate wage income and cash aid. Even for families receiving the assistance, the average benefit amounts are paltry, ranging from $300 to $400 for a family of three (Edin and Shaefer 2015), which is far from enough.

Moreover, the complex administrative requirements to access aid have led many poor families to abandon the program. Despite many unanswered phone calls, many impoverished families are unable to connect with the office that administers TANF. Some ultimately give up, discouraged by application procedures. Others fail the application process. These factors suggest that TANF is an ineffective, and insufficient system to assist non-working homeless people.

Alternative state welfare: Finland’s success in Addressing Homelessness

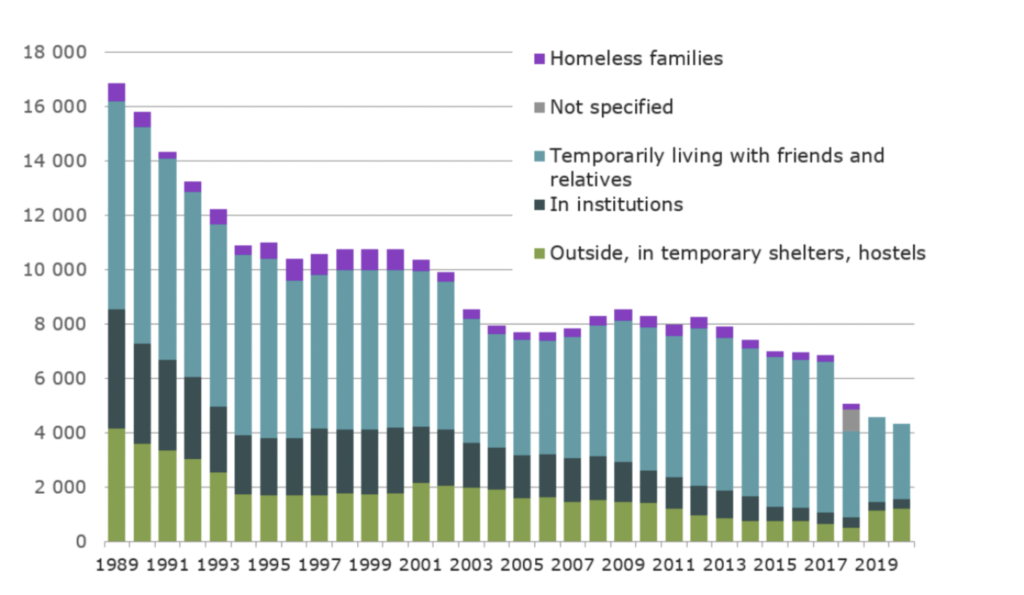

While many welfare programs find the homelessness an intractable problem to solve, Finland has successfully reduced its homeless population.

By contrast to the U.S, where TANF tries to find qualified recipients, Finland’s government instead initiated its Housing First policy in 2008 which began with offering housing directly.

The program offered permanent accommodation on a normal lease for the homeless. Depending on residents’ income, they may contribute to the cost of the support services they receive. The rest is covered by the local government (Anon 2022). Residents meet with advisors to identify the rented expenses and how to access other government resources.

As a result, Finland’s homeless population decreased drastically from 1989 to 2020:

It might be difficult to duplicate Finland’s Housing First policy but the U.S. should at minimum take the following steps to first in the U.S. aid their homeless:

- Start by offering reliable sufficient financial support

- Then help the homeless find jobs, so they can maintain a decent standard of living

- Supporting them with advisors and guides with individually tailored support services for healthcare and their finances, making the information about receiving the benefits more available.

Once these initial basic steps are introduced, it may be possible to design programs better able to prevent family homelessness.

Normalizing the Abnormal

When asked about being ignored by most who pass him on the sidewalks, Ethan had this to say:

“I’ve gotten used to it.”

Ethan

As ubiquitous as homelessness is in the United States, many housed people have become accustomed to ignoring the problem. Through this post, I want to encourage people to step out of their fixed routines and realize how we have normalized the abnormalities of homelessness and its attendant pain and suffering. Next time, when you see someone like Ethan on the street, at least notice them. They don’t belong there.

Citations:

Anon. 2022 “Here’s How Finland Solved Its Homelessness Problem.” World Economic Forum.

Edin, K. J., and &. H. Luke Shaefer. 2015. $ 2.00 a Day : Living on Almost Nothing in Amerika. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Fowler, P. J., P. S. Hovmand, K. E. Marcal, and S. Das. 2019. “Solving Homelessness from a Complex Systems Perspective: Insights for Prevention Responses.” Annual Review of Public Health.

Grogger, Jeffrey. 2003. “The Effects of Time Limits, the EITC, and Other Policy Changes on Welfare Use, Work, and Income among Female-Headed Families.” The Review of Economics and Statistics 85(2):394–408. doi: 10.1162/003465303765299891.

Harrison, Fred. 2020. “Cyclical Housing Markets and Homelessness.” American Journal of Economics and Sociology 79(2):591–612. doi: 10.1111/ajes.12322.

Heinrich, C. J. 2009. Making the Work-Based Safety Net Work Better: Forward-Looking Policies to Help Low-Income Families. Russell Sage Foundation.

Lee, Barrett A., Kimberly A. Tyler, and James D. Wright. 2010. “The New Homelessness Revisited.” Annual Review of Sociology 36(1):501–21. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-070308-115940.

Mathur, A. 2015. “TANF Is Failing The Non-Working Poor.” in TANF Is Failing The Non-Working Poor. Forbes.

McPherson, Marian. 2018. “Skyrocketing Home Prices Are Driving up Homelessness Rate.” Inman.

Ponio, J. 2022. Can We Really End Homelessness? Our Father’s House Soup.

Tach, Laura, and Kathryn Edin. 2017. “The Social Safety Net after Welfare Reform: Recent Developments and Consequences for Household Dynamics.” Annual Review of Sociology 43(1):541–61. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-060116-053300.