A Symbolic Pas de Deux

A pas de deux, directly translated to ‘step of two’, is a partnered dance in ballet, typically between a man and woman. The stereotypes for both male and female ballet dancers are translated symbolically into the traditional pas de deux. As Foster (1996) elaborates, “Pas de deux offered the female dancer considerable visibility but relatively little autonomy… Dancing with her partner, prominent as she was, her movements depended upon and were guided by his support” (205). Essentially, women are posed like dolls, molded like clay, or controlled like puppets.

Novack (1993) describes the heterosexual ideas of romance and gender norms from the nineteenth century that the pas de deux facilitate. It’s meant to starkly contrast the feminine woman and masculine man (43). The culture of ballet continues to enforce these ideals.

The Royal Ballet’s setting of the pas de deux between the Sugar Plum Fairy and her Cavalier in Act Two of the Nutcracker, a staple of classical ballet. Here gender norms are displayed as the danseur holds the ballerina up without much action himself while she is elegantly posed in a paunche. Image Source: Classical Music BBC

The Stereotype for Women: a Doll to be Posed

Stereotypes in ballet depict women as “frail, delicate, beautiful, objects, displayed and controlled by men” (Novack 1993:38). Ballerinas are instructed to be feminine by predominantly male choreographers and artistic directors, concealing the effort they have to exert to be a piece of living art. Sociologist Lesley-Anne Sayers describes the nature of femininity for ballerinas as an image of “perpetual virginity, an idealized and ethereal femininity,” (Sayers 1993:166). This description also emphasizes how the ballerina has been sexualized, an object of desire made further enticing by the fact she’s impossible to ‘have’. Yet, there is also an image of ballerinas as independent and technically proficient women, which creates a paradoxical culture that “[unites] images of power to images of being manipulated and controlled” (Novack 1993:46).

A Harmful Culture of Control over Ballerinas’ Bodies and Selves

There is a certain body type associated with ballerinas: long limbed, not too short or too tall, and thin. This ideal body is desired so as to create a corps de ballet in which no dancer is distracting by being obviously tall or having more weight, since it takes away from the homogeneity of the dancers. These stereotypes perpetuate a culture saturated with problems of anorexia and infantilization for women as both their bodies and personas are policed by other male and female dancers, teachers, choreographers, and artistic directors. Eating disorders and body dysmorphia are common results of this culture (Novack 1993:41).

Control is not just taught to be maintained over the physical body, but the person. Women dancers are taught to be submissive to the whims of the choreographer (who is typically a man). Yet, the toxicity of these practices aren’t always recognized within the ballet community, instead seen as “inseparable from artistry and devotion to great performance” (Novack 1993:41).

The Stereotype for Men: Femininity and Homosexuality

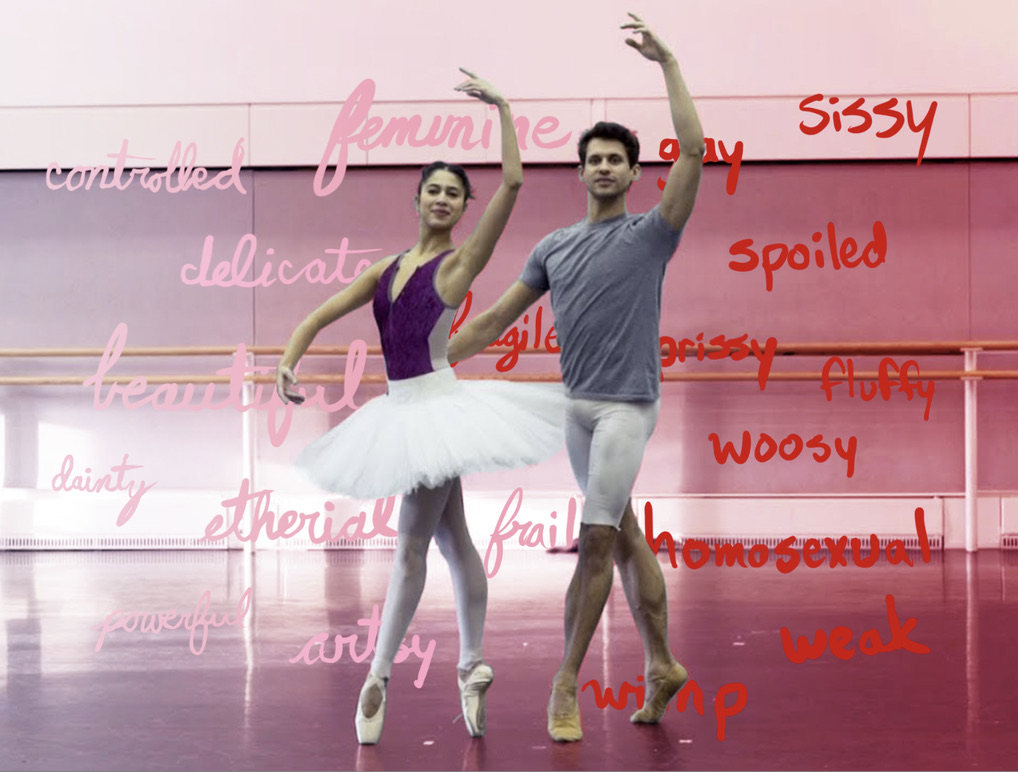

Since ballet as a whole tends to be associated with femininity, male dancers are disparaged as “feminine, wimp, spoiled, dainty, fragile, weak, fluffy, woosy, prissy, artsy, and sissy” (Fisher 2009:32). This femininity is associated with homosexuality, contributing to the myth that all men in ballet are gay.1

Ballet dancers face drastically different gendered stereotypes depending on their sex. Image source: Royal Opera House

Over the years there have been attempts at making ballet seem macho by associating with overtly heterosexual and masculine ideas through media in the form of movies and advertisements, such as the widely popular ballet movie Center Stage, which prominently features the lead male dancer riding a motorcycle and flirting with women to enforce the idea he can be both a dancer and a heterosexual, masculine man. However, as sociologist Jennifer Fisher argues, “‘making it macho’ is not a strategy that will ever work, simply because ballet isn’t conventionally macho and never will be” (Fisher 2009:43). So, male dancers wield power where they can get it over female dancers in order to compensate for the fact they are looked down upon by American society as a whole for defying the heteronormative masculine stereotype.

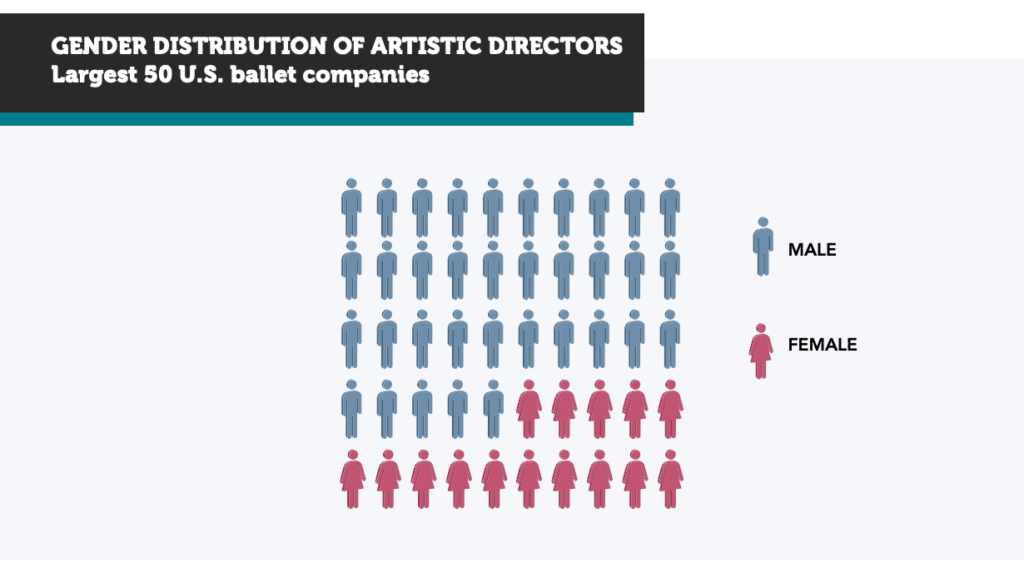

Perpetuating Male Dancer’s Control: The Glass Escalator

While it is difficult to attract men to ballet with the prevalent stereotypes of men who do ballet, once they are in, there is an expedient track for men’s advancement within the ballet world. For sociologists, the term glass escalator is used in contrast with the glass ceiling that women often face when attempting to advance in patriarchal workplaces. This is because there are fewer men who dance (Fisher 2009:36). The lesser supply of eager male dancers causes them to be catered to when they show interest, being offered scholarships, opportunities, and powerful jobs as artistic directors and choreographers. However, “it’s an odd supremacy, in that they often pay dearly for any preferred status advantages, facing prejudices that accompany their unusual career choice” (Fisher 2009:36).

Source: The Dance Data Project’s Artistic and Executive Leadership Report (2022) 70% of artistic directors for the largest 50 ballet companies in the US are male and only 30% are female.

Gender Policing

The ballet world is closed and steeped in tradition, which makes it overall resistant to change (Novack 1993:46). As Novack (1993) puts it, “one is either in the ballet world or out of the ballet world” (42). Gender roles are simply seen as a part of the culture of ballet that dancers must conform to or be shut out.

Chase Johnsey (left), a gender-fluid dancer, made waves as he performed in the all female corps of “Sleeping Beauty” for the English National Ballet. But, as Fuhrer recounts, “after his history-making moment, he found himself shut out of classical ballet” (Fuhrer 2022). Image Source: The New York Times

Challenging Norms without Change Through Humor

When gender norms are broken, such as a man dancing a female part in a ballet, it is often for a comedic effect. This extends to groups like Les Ballets Trockadero de Monte Carlo, an all male ballet company that performs in drag, and often en pointe when performing traditionally female roles. Yet, as skilled as these dancers are, there is still an underlying aspect of comedy, purposefully initiating laughter at male dancers performing female roles (Fuhrer 2022). This challenges gender norms through parodies, but doesn’t evolve them.

A promotional poster for Les Ballets Trockadero de Monte Carlo illustrates both the professional nature of the company as well as the comedy they use to allow the breaking of gender norms. Image Source: WLU

Making Changes: A New Kind of Pas de Deux

While ballet as a whole may be resistant to change, there have been recent developments within older spaces to become more inclusive as well as the founding of newer groups built on the ideas of change.

Newer companies such as Ballet22, founded in Barcelona by Chase Johnsey (aforementioned), and Alonzo King LINES Ballet work to provide a space without the enforced gender norms typical of ballet. Ballet22 is described as “a company [which] offers artists assigned male at birth a place to dance on pointe, without comedy or caricature” (Fuhrer 2022). So it is both a serious ballet company and a space without the enforced stereotypes around gender in ballet, proving such a company can exist without compromising the prestige and tradition of the art itself.

Ashton Edwards, a nonbinary ballet dancer at Pacific Northwest Ballet works en pointe and dances traditionally female roles. They have also helped to instigate change within the school to become more gender inclusive (Fuhrer 2022). Image Source: Pointe Magazine

Alonzo King’s style of choreography and company demonstrates a place in which ballet can exist in its technical aspects without the preserved gender stereotypes that permeate most of the ballet world. King’s method of casting in the pas de deux as well as other pieces has dancers embody energies or qualities, like strength or fluidity, instead of characters, irrespective of a dancer’s gender (Jenson 2009:121).

A picture of dancers who are a part of Alonzo King LINES Ballet illustrates the changed nature of gender norms as both dancers work together in an equalized power dynamic to create movement and artistry. Image Source: Alonzo King Lines Ballet

King also choreographs collaborative movements, having women take initiative to reverse the power dynamic, and shift the dancers’ angle away from fully facing front so that the dance is less performative (Jenson 2009:125). Jenson (2009) summarizes that King “was doing more than reinvigorating preconceived notions of femininity. King was changing the dynamic of ballet partnerships” (122). By changing the nature of interaction between male and female dancers, King is able to break down and move past the gender roles automatically assigned to each, evolving the culture of ballet as a whole.

Footnotes

- This is not true as research has shown that only about half of men in ballet identify as homosexual (Fisher 2009:41).

Sources

Fisher, Jennifer. 2009. “Maverick Men in Ballet: Rethinking the ‘Making it Macho’ Strategy.” Pp.31-48 in When Men Dance: Choreographing Masculinities Across Borders, edited by J. Fisher and A. Shay. New York: Oxford University Press.

Foster, Susan Leigh. 1996. Choreography and Narrative: Ballet’s Staging of Story and Desire. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Fuhrer, Margaret. 2022. “A Rising Nonbinary Swan, on Pointe,” The New York Times, April 24.

Jenson, Jill Nunes. 2009. “Transcending Gender in Ballet’s LINES.” Pp.118-145 in When Men Dance: Choreographing Masculinities Across Borders, edited by J. Fisher and A. Shay. New York: Oxford University Press.

Novack, Cynthia J. 1993. “Ballet, Gender, and Cultural Power.” Pp.34-47 in Dance, Gender, and Culture, edited by H. Thomas. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Sayers, Lesley-Anne. 1993. “‘She might pirouette on a daisy and it would not bend’ Images of Femininity and Dance Appreciation” Pp. 164-183 in Dance, Gender, and Culture, edited by H. Thomas. New York: St. Martin’s Press.