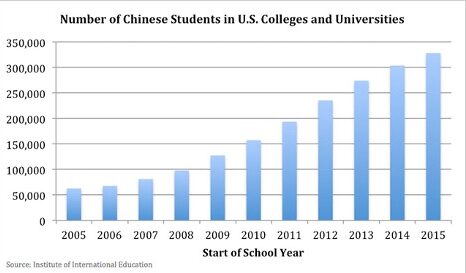

Between 2003 and 2013, the number of Chinese international students in the US rose from 61,765 to 274,439, a staggering 344% increase (Chao 2015:28). As studying abroad becomes increasingly attractive to Chinese students, cultural differences surrounding schooling continue to lead to numerous challenges for these students studying in the US. While some faculty members at US institutions are conscious of the myriad of challenges these students face studying in a foreign country where pedagogical practices are drastically different, many do not know how to support them. With more Chinese international students coming to the US, it is increasingly important for all actors at US educational institutions to understand their experiences and strategize ways to best support them.

Cultural Differences in the Classroom

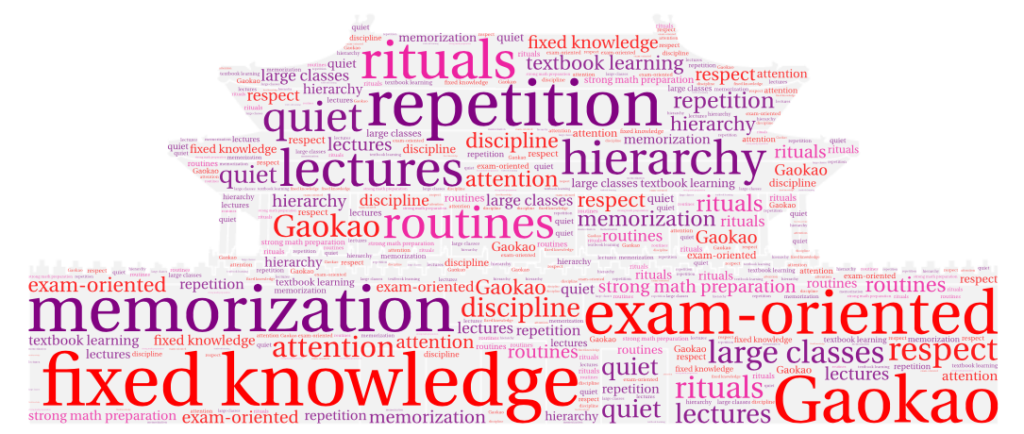

| Chinese Education | US Education |

| – Assumption that knowledge is fixed – Goal is transmission of facts – Emphasizes memorization and repetition – Less student participation – Less discussion – More lecturing – Teachers are more of an authoritative figure – Teachers ask questions looking for a correct answer – Emphasizes discipline and attention – Strict classroom rituals and routine – Singular exams hold a lot of weight – Critical thinking may exist outside of class, but those ideas are not brought into the classroom setting (Tan 2015) | – Assumption that knowledge is fluid – Goal is to acquire knowledge and become critical thinkers – Emphasizes critical thinking – Favors learning through guided exploration – Memorization present but not sole focus – Participation is encouraged – Students encouraged to develop own interpretations and ideas about course content – Teachers pose more open-ended questions to the class – Usually a casual learning environment (Ching et al. 2017) |

Chinese pedagogy is based on the idea that knowledge is fixed, so the aim of a Chinese education becomes obtaining objective information (Tan 2015:204). The lack of student participation in Chinese classrooms reflects this belief. When asked about student engagement in a Chinese classroom, a Chinese international student named Eileen1explained, “Basically we’re just sitting there, and then the teacher would say a lot of things, teach us in the front. And there’s really no discussions between students. It’s just kind of (a) lecturing kind of thing.” This core assumption about knowledge also results in prioritizing memorization. Another student named Valerie2 noted having “so many repetitive memorization tests back then.” She remembered her third year of middle school as a year of rememorizing content from the past two years. This example illustrates the emphasis on repetition for content mastery in Chinese curricula.

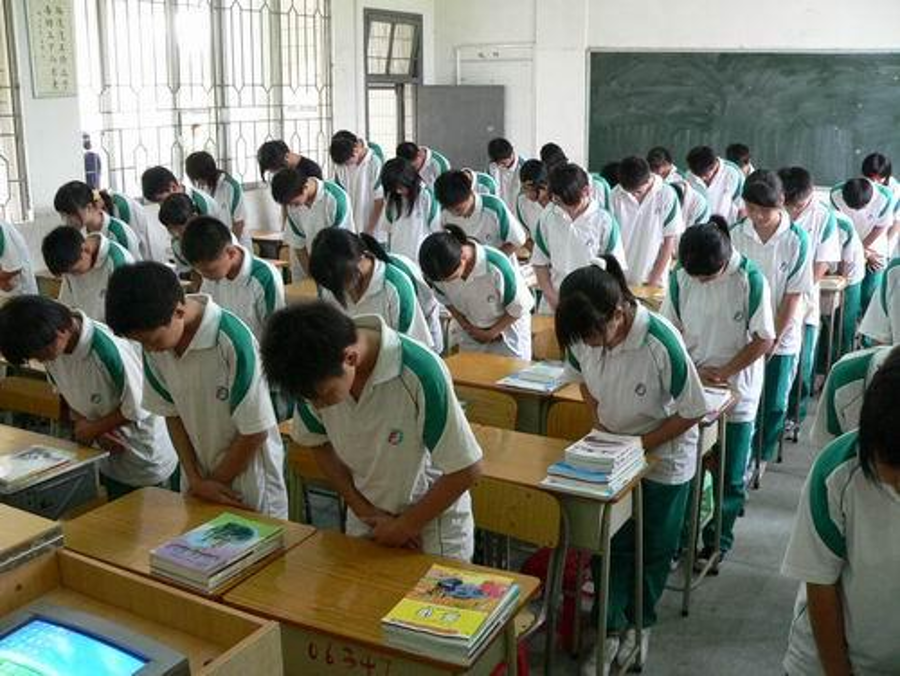

In addition, Chinese pedagogy emphasizes the importance of students’ respect for their teacher, resulting in Chinese teachers being much more of authority figures. A student named Jackson3 described his teachers as “more like a higher figure that you can hardly approach.” This idea is demonstrated by the classroom rituals in China. For instance, when the teacher arrives at the beginning of class, all students must stand and greet them. They may only sit back down once the teacher instructs them to do so (Tan 2015:200). Students are supposed to be obedient, attentive, and follow strict classroom routines, such as knowing when to open the book, when to speak, and even when to look at the chalkboard (Tan 2015:201).

Challenges for International Students in Participation

Chinese international students may find it more difficult participating in US classrooms. While Chinese classrooms expect students to listen and memorize, US classrooms encourage students to learn from each other, often through verbal student participation. This form of classroom engagement may pose a challenge for Chinese international students for whom its simply unfamiliar, but there are also other more nuanced ways this different classroom culture may challenge them. Jackson explained that he often needs to do more preparation before contributing in class because he is worried about having less background knowledge on the US related discussion topics.

Chinese international students may also find it more challenging articulating their ideas in English. Eileen mentioned, “English is not my language, like native language. So sometimes . . . I can’t really think of the words I want to use.”

Challenges with Critical Analysis

Not just with participation, Chinese students may also face difficulty with critical analysis. When asking Chinese international students their reaction the first time they were asked to provide critical analysis in a US classroom, a common response has been: “We have no idea how to be critical and critical of what” (Zhang 2017:866). Since Chinese teachers teach information labeled as “‘objective’ truths (Tan 2020:7),” these students have had minimal training in critical thinking (Zhang 2017). Eileen expressed feeling that domestic students always have more sophisticated analyses, which makes her feel self-conscious when sharing her own ideas.

Valerie expressed that since she started doing critical analysis here, she has realized that her ideas often differ from those of her domestic peers. She explained, “The biggest challenge for me is to be brave enough to stick up for my different opinions [than] everyone else, because most of them may hold one opinion … And I think of something else because I grew up in another place.”

Ways to Support Chinese International Students

Keeping these challenges in mind, there are ways to support Chinese international students. Faculty members could engage students in ways that rely less on impromptu linguistic abilities (Ching et al. 2017). They should implement participation strategies that give students more time to prepare before contributing to a discussion. Even simply being aware and empathetic of cultural differences may reassure these students.

Students struggle in different ways depending on their education background and other individual differences, so support for Chinese students would also benefit other students who struggle in similar ways. Student participation methods that bypass the language barrier would benefit all international students. Similarly, more preparation time before participation would alleviate stress for more introverted students.

References

Chao, Chiangnan. 2015 “Decision Making for Chinese Students to Receive their Higher Education in the U.S.”International Journal of Higher Education. 5(1). Retrieved April 14, 2022 (https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1082102.pdf)

Ching, Yuerong, Susan L. Renes, Samantha McMurrow, Joni Simpson, and Anthony T. Strange. 2017 “Challenges facing Chinese International students studying in the United States.” Educational Research and Reviews. 12(8). Retrieved March 30, 2022 (https://academicjournals.org/journal/ERR/article-abstract/F22B2EE63940)

Tan, Charlene. 2020 “Conceptions and Practices of Critical Thinking in Chinese Schools: An Example from Shanghai.” Educational Studies: A Journal of the American Educational Studies Association 56(4). Retrieved March 30, 2022 (https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00131946.2020.1757446)

Tan, Charlene. 2015. “Education policy borrowing and cultural scripts for teaching in China.” Comparative Education51(2). Retrieved February 24, 2022 (https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/03050068.2014.966485’)

Wang, Hairong. 2015. “An Education Lesson.” Beijing Review, Retrieved May 2, 2022 (https://www.bjreview.com/Nation/201509/t20150914_800038115.html)

Zhang, Tao. 2017 “Why do Chinese postgraduates struggle with critical thinking? Some clues from the higher education curriculum in China.” Journal of Further and Higher Education 41(6). Retrieved March 30, 2022 (https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/0309877X.2016.1206857).

1 Pseudonym for a first-year student at Hamilton College from Beijing

2 Pseudonym for another first-year student at Hamilton College also from Beijing

3 Pseudonym for a first-year student at Hamilton College from Zhejiang, China