Max Gersch

As of 2015, only two Museums in Iraq have pieces from Nimrud.1 These museums include (from top left): The British Museum, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Bowdoin College Art Museum, the Met, Museu Calouste Gulbenkian, the State Hermitage, the Louvre, the Walters Museum, and The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts.

Growing up in a Washington, D.C. daycare, I spent many days wandering through the Smithsonian admiring the breathtaking exhibits, but I took for granted how those museums acquired their art and never wondered how it got where it was.

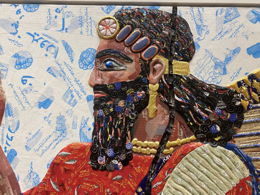

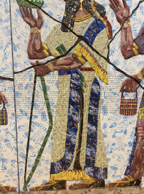

Michael Rakowitz’s current exhibit, Nimrud, at the Wellin Museum at Hamilton College raises provocative questions about the ethics of colonial art collections in western countries. Can the presence of colonial art in western countries ever be justified? How can colonial powers rectify past wrongs and continue to honor the art of former colonies if they repatriate the art?

Rakowitz’s artwork emulates statues from the Ancient Assyrian city of Nimrud’s Northwest Palace. The original sculptures reside all over the world, but only a few pieces are left in Iraq. Surely the right place for ancient and valuable works of art is their home.

But in a devastating twist of fate, the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) destroyed the original sculptures from the Palace when the caliphate captured Mosul in 2015. The quotes below from the exhibit demonstrate the anguish that destruction caused residents of the city

I ALMOST SPENT MY WHOLE LIFE IN THE ANCIENT SITES OF MOSUL. THESE GANGS DIDN’T ONLY DESTROY MY CITY, THEY HAVE DESTROYED THE DEAREST THINGS TO MY HEART.” — AMER AL-JUMAILY

“ONE HUNDRED PERCENT DESTROYED. LOSING NIMRUD IS MORE PAINFUL TO ME THAN EVEN LOSING MY OWN HOUSE” — ALI AL BAYANI

Individuals like Al-Jumaily and Al Bayani both value the heritage the sculptures at Nimrud represented. In an ideal world, those artifacts would be where they belong, in their home countries. In the case of the art from Nimrud, however, colonial art transfers, unexpectedly, are the only reason art from ancient Assyria survives today. That is not to excuse colonial transfers, but to emphasize that the relations to stolen art can be myriad and complex.

In a broader sense, “political sovereignty and visual sovereignty are inextricably tied” as Kathleen Ash-Milby and Ruth B. Phillips in the Art Journal. The ability for post-colonial nations to exercise power and agency over their former art is a significant demonstration of independence.

So what can be done? Both Ash-Milby, Philips, and other scholars of colonialism and art, emphasize the importance of dialogue. These problems will not be solved overnight, and there is not a one-size-fits all solution. As Ash-Milby and Philips write, “sovereignty should be understood as both processual and relational.”[4] Dr. Tolia-Kelley of the University of Sussex agrees: “there is room for dialogue that is empowering, re-enlivening, and can potentially lead to a re-framing of a postcolonial, post-racial sensibility of curatorship.”[5]

This is where the Rakowitz exhibit shines. The Rakowitz exhibit creates and inspires that necessary dialogue. It starts the process of discussing sovereignty. The exhibit shows that each story has more than two sides. It evokes emotion, enough to demand a response, a solution, a remedy to the obvious injustice dealt to the Iraqi people. Colonial powers holding stolen art must engage Iraqi people, as well as post-colonial nations across the globe, in a dialogue and extend to them that vital visual sovereignty.

Rakowitz also shows that colonial powers can honor the artwork of colonized peoples by emulating their creations. Imitation is, after all, the highest form of flattery. Rakowitz, who has Jewish Iraqi ancestry, is at the center of these issues of colonialism and art. He can make legitimate claims to the original artwork from Nimrud, while also claiming fidelity to the United States, a colonial power. His exhibit is perhaps the best outcome. If art can be returned by colonial powers to where it came from, emulation in Rakowitz’s style is the most respectful and meaningful replacement to continue to honor and appreciate the artwork.

1 Ruth Horry, “Museums Worldwide Holding Material from Nimrud,” Nimrud: Materialities of Assyrian Knowledge Production (Nimrud Project, Department of History and Philosophy of Science, University of Cambridge, Free School Lane, Cambridge CB2 3RH, UK, 2015), http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/nimrud/catalogues/museumsworldwide/index.html.

2. “Michael Rakowitz: Nimrud October 19, 2020 – June 18, 2021 – Wellin Museum,” Wellin Museum of Art, accessed May 2, 2021, https://www.hamilton.edu/wellin/exhibitions/detail/michael-rakowitz-nimrud.

3. Lucy Kafanov, “Iraqis Mourn Destruction of Ancient City of Nimrud: ISIS ‘Tried to Destroy the Identity of Iraq’,” NBCNews.com (NBCUniversal News Group, December 12, 2016), https://www.nbcnews.com/storyline/isis-terror/iraqis-mourn-destruction-ancient-city-nimrud-isis-tried-destroy-identity-n694636.

4. Ash-Milby, Kathleen, and Ruth B. Phillips. “Inclusivity or Sovereignty? Native American Arts in the Gallery and the Museum since 1992.” Art Journal 76, no. 2 (2017): 10-38. Accessed April 28, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/45142470.

[5] Tolia-Kelly, Divya P. “Feeling and Being at the (Postcolonial) Museum: Presencing the Affective Politics of ‘Race’ and Culture.” Sociology 50, no. 5 (2016): 896-912. Accessed April 28, 2021. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26556373.