When you drink a cup of tea, have you ever thought about the story of the people and places involved in its production? Whether or not you have, the story of tea is likely much more complex than it seems. Tea production is surrounded with romanticized images of nature that ignore the colonial roots of plantations and exploitation of the workers.1

How is tea made?

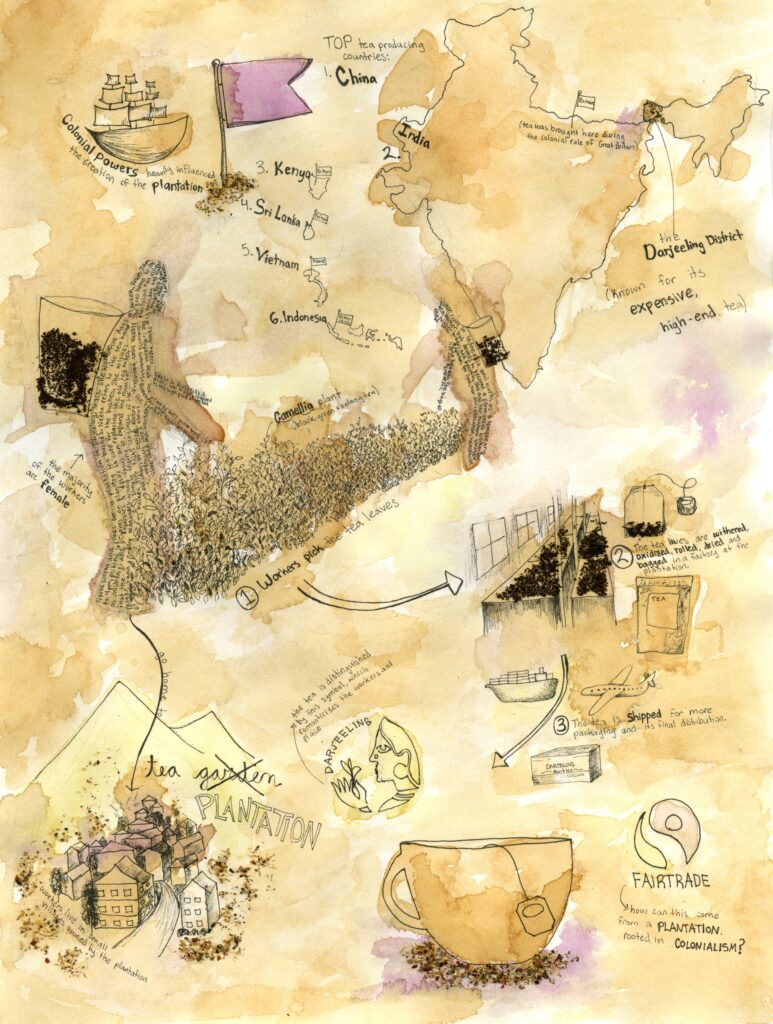

The top six tea producing countries are China, India, Kenya, Sri Lanka, Vietnam, and Indonesia.2 In almost every country that grows a significant amount of tea, with the exception of China, colonial powers created the tea industry.3,4

The Darjeeling region of India, known for its high-end Darjeeling tea, consists only of plantations, where workers live and work on land they do not own.5 Tea production begins with the Camellia plant, which can be made into black, green, or oolong tea.

- Female workers typically spend over 50 hours a week picking the leaves.6

- The tea leaves are then driven to a nearby factory, where machines and workers (male and female) wither, oxidize, roll, dry, and bag the tea.7

- The tea is driven and shipped to more factories for its final packaging and distribution.8

Darjeeling tea is labeled by a Geographical Indication (GI), which certifies that it actually comes from the Darjeeling district, and thus marks Darjeeling and the workers as important for their geographical place. Romanticizing the workers’ care for nature, portraying tea plantations as gardens, fetishizing the workers, and promoting the natural political place of the workers turns Darjeeling tea into an exotic, luxurious product intertwined with notions of social justice.9

What are the environmental effects?

The production of 1 kg of Darjeeling black tea (over 400 servings), from the growing to the shipping to the water used in consumption, emits 9 kg of CO2 equivalent.10,11 This is approximately equal to burning 1 gallon of gasoline.12

Who is involved in the production of tea?

In the Darjeeling district in India, the British Empire recruited ethnic Gorkha workers for the plantations in the 1850s. Now, the Gorkha people make up the majority of the workforce in Darjeeling and are focused on gaining sovereignty and control over the land, centering decolonization in their movement for justice.13

Workers on Darjeeling’s plantations struggle to pay for food and their children’s education with their pay of just over one dollar a day. Yet, the focus on increased wages in the fair-trade movement does not end workers’ exploitation. The women on the plantations desire a system of care, specifically a focus on community spaces within the plantation-controlled villages, including gardens and schools.14

The life-long, generational aspect of plantation workers’ jobs and seventy-year lifespan of the tea plants both demonstrate the permanency of the workers and tea plants. Workers reflect this relationship in their focus on the future of the land and their families. They wish that plantation managers would invest in the future by caring for the already existing plants, rather than increasing profits by planting more.15

The workers in Darjeeling are inextricably linked with the plantation, colonial history, and landscape. Although social justice movements use nature and the environment to view the tea industry as fair, imagining an equitable tea industry within a historically colonial, capitalist plantation is contradictory. Instead, social justice movements need to move beyond simply raising wages and work outside of the capitalist plantation to focus on workers’ desires for care, community, and control over their land.16

[1] Besky, Sarah. The Darjeeling Distinction : Labor and Justice on Fair-Trade Tea Plantations in India . University of California Press, 2013, doi:10.1525/9780520957602, https://web.b.ebscohost.com/ehost/ebookviewer/ebook?sid=644befa9-8c4b-421a-9295-f71da86ecf0d%40pdc-v-sessmgr01&vid=0&format=EB.

[2, 3] Chen, Alice. “The World’s Top Tea-Producing Countries.” The World Status, 17 September 2020, https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/the-worlds-top-10-tea-producing-nations.html.

[4, 5, 6, 7] Besky.

[8] – Cichorowski, Georg, et al. “Scenario Analysis of Life Cycle Greenhouse Gas Emissions of Darjeeling Tea.” The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment, vol. 20, no. 4, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2015, pp. 426–39, https://search.proquest.com/docview/1671991249/fulltextPDF/57ADE4DD79A042E1PQ/1?accountid=11264.

[9] Besky.

[10] Cichorowski et al.

[11] “How Much Loose Leaf Tea to Buy.” It’s More Than Tea, 23 May 2017, https://itsmorethantea.wordpress.com/2017/05/23/how-much-loose-leaf-tea-to-buy/.

[12] “Greenhouse Gas Emissions From A Typical Passenger Vehicle.” EPA National Service Center for Environmental Publications, May 2014, https://nepis.epa.gov/Exe/ZyNET.exe/P100JPPH.TXT?ZyActionD=ZyDocument&Client=EPA&Index=2011+Thru+2015&Docs=&Query=&Time=&EndTime=&SearchMethod=1&TocRestrict=n&Toc=&TocEntry=&QField=&QFieldYear=&QFieldMonth=&QFieldDay=&IntQFieldOp=0&ExtQFieldOp=0&XmlQuery=&File=D%3A%5Czyfiles%5CIndex%20Data%5C11thru15%5CTxt%5C00000011%5CP100JPPH.txt&User=ANONYMOUS&Password=anonymous&SortMethod=h%7C-&MaximumDocuments=1&FuzzyDegree=0&ImageQuality=r75g8/r75g8/x150y150g16/i425&Display=hpfr&DefSeekPage=x&SearchBack=ZyActionL&Back=ZyActionS&BackDesc=Results%20page&MaximumPages=1&ZyEntry=1&SeekPage=x&ZyPURL.

[13, 14, 15, 16] Besky.

Sharma, Dinesh C. “Indian Darjeeling Tea Faces Climate Risk.” Research Stash, 17 May 2018, https://www.researchstash.com/2018/05/17/indian-darjeeling-tea-faces-climate-risk/.

Janich, Michael (2005). Darjeeling Panorama [Photograph]. “Darjeeling.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Darjeeling#/media/File:Darjeeling.jpg.

Kustanti, Veronika Ratri, and Theresia Widiyanti. “Research on supply chain in the tea sector in Indonesia.” Jakarta: The Business Watch Indonesia (2007), https://www.somo.nl/wp-content/uploads/2007/01/Research-on-Supply-Chain-in-the-Tea-Sector-in-Indonesia.pdf.