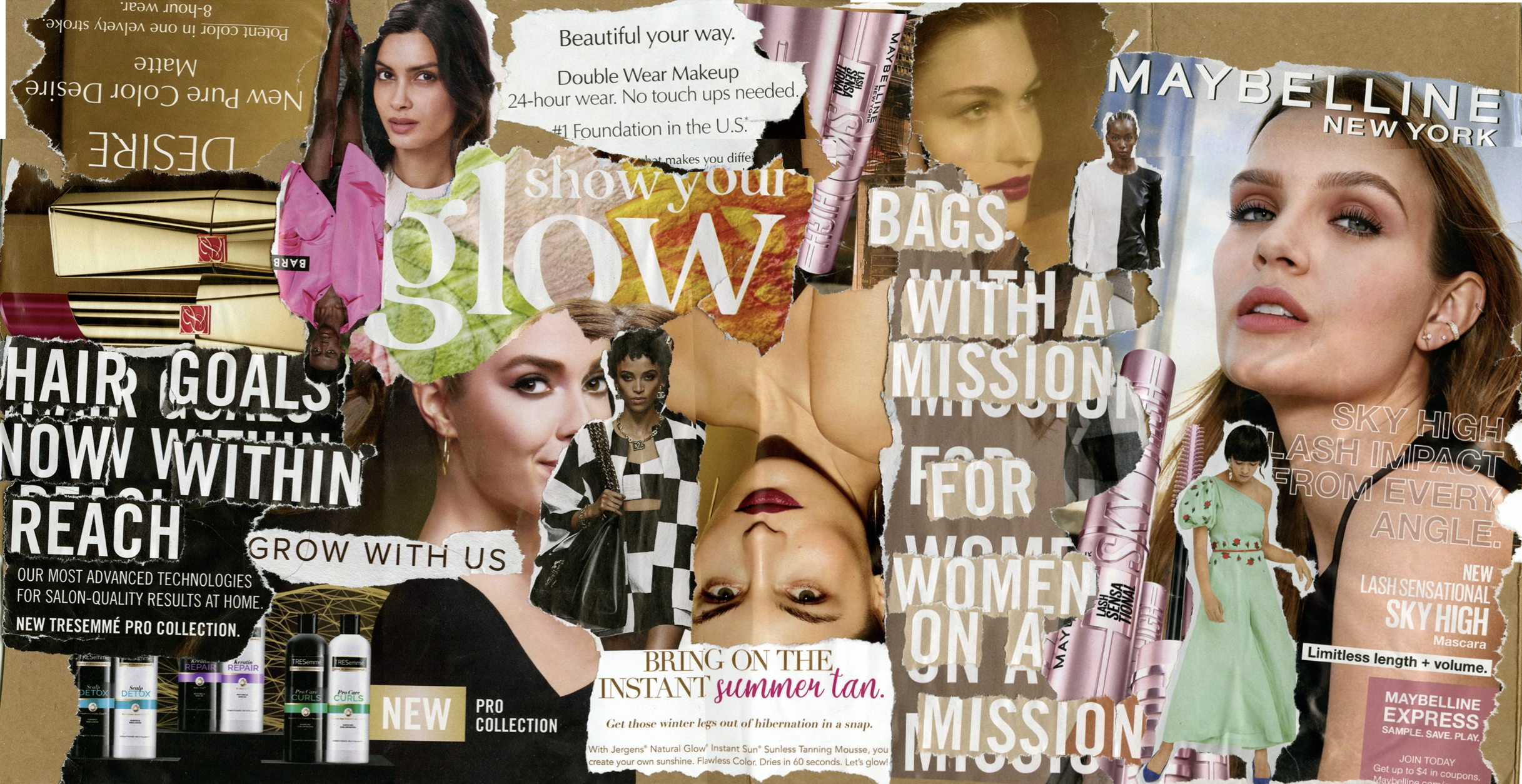

It’s no secret that beauty products are expensive. According to Business Insider, the beauty industry was worth $532 billion in 2019. Magazine ads use appealing images and seemingly empowering language to say: buy our expensive product and you, too, will be enough. Such popular imaging sets the standards that women compare themselves to.

So how does the commodification of beauty affect women?

These beauty goods serve as tools for women to perform different forms of femininity. Even from a young age, women are socialized to care about looking “pretty” and maintain a feminine appearance. Their “success” affects the way others view them, especially their professional competence. Beauty maintenance reflects a “third shift” that women must take in order to prove their competence and character (Kang 2010, 15). If they fail, consequences include being ridden off as unprofessional. Sociologists at UT Austin find that makeup use increases others’ perceptions of users’ credibility, heterosexuality, and health, which ultimately can boost confidence at work (Dellinger & Williams 1997).

Women of Color who must conform to white beauty standards are particularly at risk of judgement from employers, clients, and others who hold positions of power.

Women’s own beauty tastes, though displaying certain degrees of agency, reflect raced and classed standards. Women’s preferences stem from the way the cultures in which they are raised and their bodies, and represent the differences in ideals between groups. For example, as Miliann Kang finds in her book The Managed Hand (2010), upper class white women tend to prefer lighter, muted tones for their nails, and view brighter colors or designs as “tacky,” though these options are staples in other communities. If not their nails, Black women’s natural hair is often written off as unprofessional in workplace codes of conduct (Griffin 2019). These examples show how white people police expectations in color-blind racist ways by depicting styles popular in communities of color as unprofessional or lower class.

The language in magazine ads, though often appearing empowering, insinuates that this strength is contingent on some monetary purchase and cultural imitation in alignment with hegemonic white beauty standards. Even when magazines or advertisements show Women of Color, their images often still conform to white standards (Rajendrah, Rashid, & Mohamed 2017). Popular culture perpetuates these harmful standards, but by recognizing their harmful biases we can work towards reversing them.

Bibliography

Basil G. Englis, Michael R. Solomon, and Richard D. Ashmore. “Beauty before the Eyes of Beholders: The Cultural Encoding of Beauty Types in Magazine Advertising and Music Television.” Journal of Advertising 23, no. 2 (1994): 49-64. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4188927.

Biron, Bethany. “Beauty has blown up to be a $532 billion industry — and analysts say that these 4 trends will make it even bigger.” Business Insider, July 9, 2019. https://www.businessinsider.com/beauty-multibillion-industry-trends-future-2019-7.

Dellinger, Kristen & Williams, Christine. “Makeup at Work: Negotiating Appearance Rules in the Workplace.” Gender and Society 11, no. 2 (April 1997): 151-177. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/089124397011002002

Gimlin, D. (2002). Body Work : Beauty and Self-Image in American Culture . University of California Press. https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520926868

Griffin, Chanté. “How Natural Black Hair at Work Became a Civil Rights Issue.” JStor Daily, July 3, 2019. https://daily.jstor.org/how-natural-black-hair-at-work-became-a-civil-rights-issue/.

Kang, M. (2010). The managed hand: race, gender, and the body in beauty service work (1st ed.). University of California Press. https://doi.org/10.1525/j.ctt1ppzfz.

Peiss, Kathy. “On Beauty… and the History of Business.” Enterprise & Society 1, no. 3 (2000): 485-506. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23699594.

Rajendrah, Sujanna, R. A. Rashid, and Saiful Bahri Mohamed. “The impact of advertisements on the conceptualisation of ideal female beauty: A systematic review.” Man in India 97, no. 16 (2017): 361-369. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Radzuwan-Ab-Rashid/publication/320550642_The_impact_of_advertisements_on_the_conceptualisation_of_ideal_female_beauty_A_systematic_review/links/5a0d03f4a6fdcc39e9bfbcf8/The-impact-of-advertisements-on-the-conceptualisation-of-ideal-female-beauty-A-systematic-review.pdf